Jun 4th 2015, 15:12 BY THE DATA TEAM, economist.com

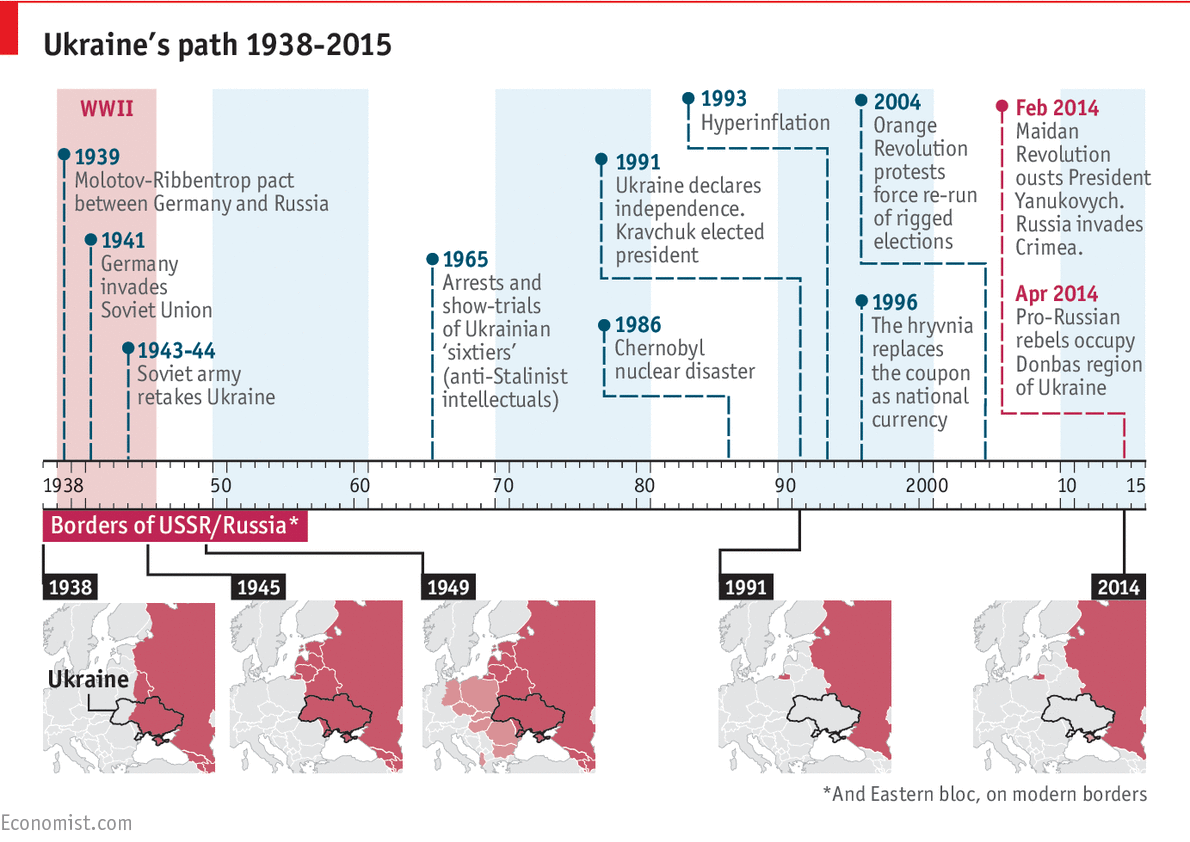

THOUGH Ukraine became independent when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, it remained largely dependent on Moscow in the ensuing decades. The Orange Revolution in 2004 promised new beginnings. But the post-revolutionary government ultimately succumbed to infighting and scandals, paving the way for Viktor Yanukovych, who won the presidency in 2010. Mr Yanukovych’s rampant corruption and his failure to deliver on a promise to bring Ukraine closer to the European Union brought demonstrators to the streets again in late 2013. Those pro-Western protests became the Maidan revolution, which ended with Mr Yanukovych fleeing in February 2014. Russia responded by swiftly annexing Crimea (where it still had a significant naval base) and stoking a separatist war in Ukraine’s east. The ensuing crisis has left thousands dead and displaced millions more. Ukraine has been pushed to the brink of economic collapse, while Russia and the West’s relations have hit a post-Cold War nadir.

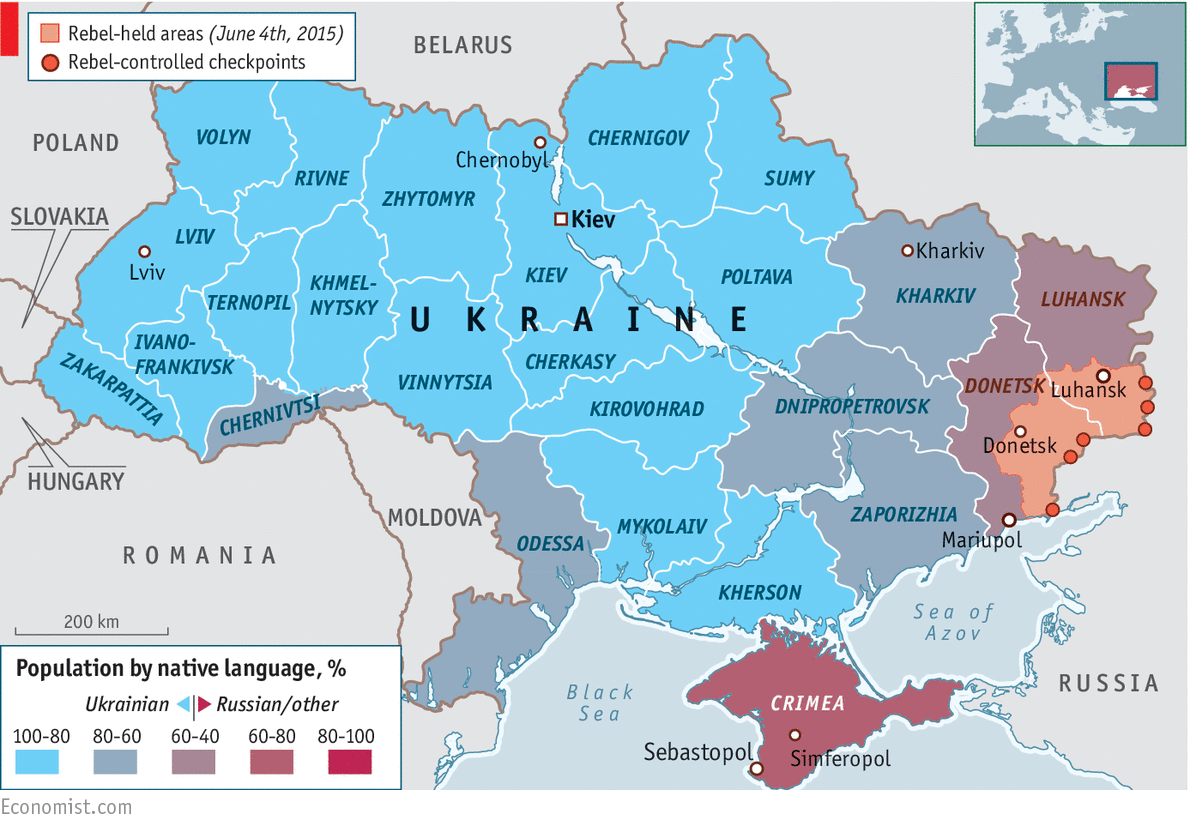

Internal divisions have haunted Ukraine ever since its independence. The east and south, which are primarily Russian-speaking and prone to Soviet nostalgia, tend to favour closer ties with Russia. Ukraine’s west, parts of which belonged to Poland until the second world war, is mostly Ukrainian-speaking and inclined towards integration with the European Union. Ukrainian politicians long exploited these divides for electoral gains; in 2014, the Kremlin played on them to ignite separatist rebellions in Donetsk and Luhansk, two of Ukraine’s easternmost provinces. The separatists there declared “people’s republics,” and waged open war with Moscow’s support. Though a ceasefire was agreed in Minsk in February, fighting continues all along the front lines.

When the Iron Curtain came down, Ukraine and Poland stood on similar economic footing, with nearly identical GDP per capita. While Poland reformed quickly and took in generous Western development aid, Ukraine succumbed to murky privatisations and endemic corruption. Successive Ukrainian governments failed to root out graft or modernise the economy. Now Poles are three times richer than Ukrainians, who are actually poorer now than they were at the end of the Soviet era.

Ukraine’s economic fortunes looked bleak even before the Maidan. A year and a half of war and revolution have only compounded the problems. Industrial production has collapsed as fighting shut down mines and factories in the country’s east. GDP fell by nearly 18% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2015, worse than even the pessimistic projections. In April, inflation topped 60% due mostly to utility price hikes. Though Ukraine’s currency, the hryvnia, has rebounded a bit and stabilised after crashing in February, efforts to prop it up have depleted the government’s coffers, leaving Ukraine with less than $10bn in foreign reserves. Now the country is dependent on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other international donors to keep it afloat.

No comments:

Post a Comment