[JB question to the author: How would you describe the U.S. Declaration of Independence from Great Britain? More generally, colonies separating themselves from oppressive empires? More recently, the peaceful division of Czechoslovakia? And the admittedly imperfect solution to the break-up of Yugoslavia? All "terrible ideas"? Key question of course: Will eventually the USA "approve" the break-up of Ukraine?]

vox.com

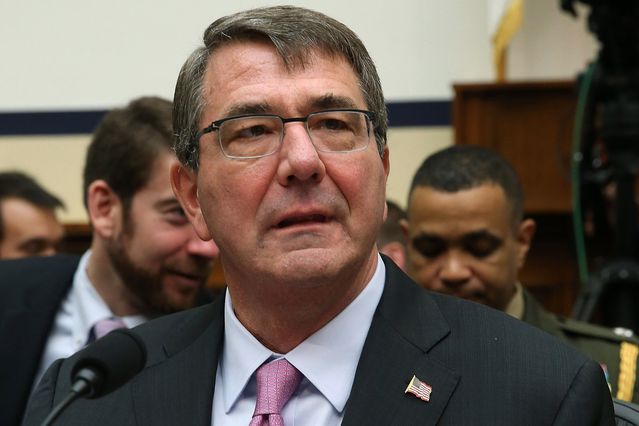

US Defense Secretary Ash Carter, in congressional testimony on Wednesday, put voice to an idea that has been rattling around US government offices for the past few months: The state of Iraq may be so irreparably broken that it can never be put back together again, and perhaps should one day be formally partitioned into separate states.

This is an idea that has been growing in popularity within the US government — in both parties, in Congress and in the Obama administration, in multiple agencies. It is attractive because it promises a relatively easy solution to a terrible problem. But it is a false promise. Partition would entrench Iraq's problems rather than solve them.

"There will not be a single state of Iraq"

Carter's statement was prompted by a question from Rep. Adam Smith, the ranking Democrat of the House Armed Services Committee, who in the course of asking how the US could respond to the chaos in Syria and Iraq, said, "Iraq is fractured. You can make a pretty powerful argument, in fact, that Iraq is no more."

"The question [is] what if a multisectarian Iraq turns out not to be possible," Carter responded, referring to the idea of Iraq as it presently exists, a state that encompasses Kurds, Arab Sunnis, and Arab Shias. "If that government can't do what it's supposed to do, then we will still try to enable local ground forces, if they're willing to partner with us, to keep stability in Iraq, but there will not be a single state of Iraq."

What Carter is suggesting is both radically new and not new at all. Never before has a senior administration official suggested this could be policy. But the idea of splitting Iraq into separate states has been floating around since the first disastrous years of the Iraq War, when then–Senator Joe Biden proposed a less extreme version: dividing it into three semi-autonomous regions. At the time, Biden was widely mocked for the idea. Eventually, the US-led forces joined with local militias and others to restore order and handed over Iraq to a powerful central government. It looked like Iraq would continue as a state.

But Iraq fell apart pretty quickly after the US-led occupation forces left. That may have been inevitable: The chaos and violence of the war's initial phase had forced many Iraqis to default to sectarian identities, to see themselves in a zero-sum contest with other sectarian groups and act accordingly. Iraq's early governments, led by openly sectarian Shia strongmen, made this worse.

The idea of a unified Iraq now looks far less certain. The predominantly Kurdish region is de facto autonomous. Much of the predominantly Sunni Arab region is dominated by ISIS. The predominantly Shia Arab region, which is home to the central government in the more-diverse Baghdad, is struggling to defeat ISIS and reunify the country. But that might be hopeless, as Sunnis may never submit to Baghdad's rule again, and Kurds probably just don't have to.

Carter is merely giving voice to what a lot of administration officials, members of Congress, and analysts have been saying for a while: The Iraqi state is so broken that it can never be put back together again, and we're better off recognizing that fact and maybe even helping to make it happen.

Peace by partition is not a solution for Iraq

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3813038/GettyImages-476439712.0.jpg)

Iraqi Shia militiamen north of Tikrit. (AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP/Getty)

Maybe this really is the least-bad option for Iraq. Maybe the idea of Shia-dominated Baghdad ruling over the Sunni regions is such a hopeless cause that trying to make it happen can only perpetuate conflict.

But it's also worth recalling why Biden's more modest proposal from 2006 was so roundly mocked. Carving up states as a means for ending conflict has a mixed track record. In the former Yugoslavia, it has worked to some extent, but after a decade of war and still-ongoing NATO peacekeeping operations. Tiny Cyprus was de facto divided by Greek-Turkish communal violence in 1964 and has had its sectarian border policed by UN peacekeepers for 50 years and counting. Is the US going to recommit tens of thousands of peacekeepers to enforce the new borders, possibly for generations? I really doubt it.

And those were the success stories; elsewhere, peace by partition has been disastrous. Dividing up India and Pakistan was meant to solve sectarianism. Instead, it led to the forced migration of an estimated 12 to 14 million people, and triggered massive, violent attacks on civilians that killed thousands more. Post-partition, those tensions went from internal to interstate, with India and Pakistan fighting multiple wars and in at least one instance coming to the brink of nuclear war. Today, their proxy conflict is one of the drivers of the chaos in Afghanistan.

The idea of partitioning Iraq was rightly derided in 2006 and looks even dicier today. It offers the false hope of a solution to the problem of sectarianism among Sunni Arabs. Presumably, the idea is that the world would promise Sunni Arabs their own state in exchange for helping drive out ISIS. But there is a reason Sunni Arabs were willing to embrace ISIS and its violent sectarianism: Those ideas are popular.

Rewarding Sunnis with more sectarianism, permanently enshrined in an explicitly sectarian state, is going to worsen that problem, not solve it. For one thing, minorities in that region are already in constant peril; that peril is likely to increase if Sunni Iraq becomes an officially sectarian state. And partition will create many new minorities: The Shias left in the post-partition Sunni state and the Sunnis in the post-partition Shia state will be vulnerable to ethnic cleansing.

And perhaps more importantly, Iraq's problems do not exist in isolation. Rather, they are just one part of a Middle East divided by sectarianism, driven both at the grassroots level and by regional states such as Saudi Arabia and Iran that foment it to serve their own interests. Handing Saudi Arabia and Iran new sectarian proxy states is going to entrench that problem, not solve it.

You can't solve sectarianism by permanently institutionalizing it

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3813048/GettyImages-474874516.0.jpg)

An Iraqi Shia militaman near Baghdad. (AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP/Getty)

I understand where the enthusiasm for dividing Iraq comes from. This problem of sectarianism is a really difficult one. Iraqis are not helping, and indeed appear intent on creating de facto independent sectarian states, so why are we standing in their way? Why are we trying to impose our solution on them?

But enshrining sectarianism in new state borders is not a solution for the problem at all. Rather, it is just a way of avoiding it by pretending it's not a problem at all, like trying to ignore the elephant in the room by dressing it up as a sofa. The fact that Iraqis want this does not make it any wiser or sounder.

The only real way to solve sectarianism is by solving sectarianism, to overcome it by getting people to abandon the idea that they exist in a zero-sum contest for security with other sectarian groups that can only be regarded as innately hostile. It means building a new social contract in which security and rights are guaranteed irrespective of ethnicity or religion, signing everyone on to that new contract, and then proving it can actually work.

That is a tremendous political and military challenge that will take years or decades. But the partition "solution" is not actually any easier — it just pretends to be — and it virtually guarantees that the underlying problems will remain and continue to trouble the region.

Yes, this is all a terribly unattractive slog of a solution to Iraq's yearslong crisis. But that is what we signed up for, whether we knew it or not, when we first created this mess by invading in 2003.

No comments:

Post a Comment