SPECIAL FEATURE

"...knife a Romanoff whereever you find him..."

MARK TWAIN ON CZARS, SIBERIA AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

[The spelling of many Russian names varies in American sources because the Russian alphabet does not transliterate directly into the English alphabet. Spellings of Russian names are often translated using phonetic sounds rather than equivalent letters which accounts for variant spellings in different quoted sources throughout this article.]

MARK TWAIN VISITS RUSSIA, 1867

Mark Twain's first encounter with the ruling Romanov family of Russia was in August 1867 when he met Czar Alexander II in Yalta, during the Quaker Cityexcursion to Europe and the Holy Land. The owners of the ship Quaker City were hoping to interest Czar Alexander II in buying the ship and a visit with him was included in the tour's itinerary.

Russia, an American ally, had supported the Union efforts during the recent American Civil War. Supporters of the Czar compared him with President Abraham Lincoln. In 1861 Czar Alexander II had issued an Emancipation Manifesto that abolished Russian serfdom -- an economic system built around peasant farm labor. Russian serfs were tied to the land on which they lived and, in effect, were human property of wealthy noblemen. Although serfs or peasants could not be sold, the land they were tied to could be sold. Estates were described as containing so many "souls" and when land was sold, it was valued at so much per "soul." It was an economic system that shared characteristics with the forced labor of black slaves in the United States. Czar Alexander II's Emancipation Manifesto was equated with Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of 1862 which expressed the principal that the United States government was finally taking a stand against slavery.

Twain was selected by his fellow travelers to help write a speech addressing Alexander II. The speech was delivered by the American consul to Russia.

The speech written by Mark Twain and signed by him as "Samuel Clemens."

Included in Twain's address to the Czar was the passage, "One of the brightest pages that has graced the world's history, since written history had its birth, was recorded by your Majesty's hand when it loosed the bonds of twenty millions of men, and Americans can but esteem it a privilege to do honour to a ruler who has wrought so great a deed."

From Mark Twain: A Biography by Albert Bigelow Paine, p. 333. |

In describing this meeting in Innocents Abroad, Twain wrote:

Taking the kind expression that is in the Emperor's face and the gentleness that is in his young daughter's into consideration, I wondered if it would not tax the Czar's firmness to the utmost to condemn a supplicating wretch to misery in the wastes of Siberia if she pleaded for him. … It seemed strange -- stranger than I can tell -- to think that the central figure in the cluster of men and women, chatting here under the trees like the most ordinary individual in the land, was a man who could open his lips and ships would fly through the waves, locomotives would speed over the plains, couriers would hurry from village to village, a hundred telegraphs would flash the word to the four corners of an Empire that stretches its vast proportions over a seventh part of the habitable globe, and a countless multitude of men would spring to do his bidding. I had a sort of vague desire to examine his hands and see if they were of flesh and blood, like other men's. Here was a man who could do this wonderful thing, and yet if I chose I could knock him down. The case was plain, but it seemed preposterous, nevertheless -- as preposterous as trying to knock down a mountain or wipe out a continent. If this man sprained his ankle, a million miles of telegraph would carry the news over mountains -- valleys -- uninhabited deserts -- under the trackless sea -- and ten thousand newspapers would prate of it; if he were grievously ill, all the nations would know it before the sun rose again; if he dropped lifeless where he stood, his fall might shake the thrones of half a world! If I could have stolen his coat, I would have done it. When I meet a man like that, I want something to remember him by (1).

Czar Alexander II (1818-1881)

Mark Twain met Czar Alexander II in Yalta in August 1867.

Photo from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. |

_____

"O'SHAH," 1873

Mark Twain's high regard for the Russian aristocracy was firmly intact in the summer of 1873 when he accepted an assignment from the

New York Herald newspaper to cover the visit of the Shah of Persia, Nasr-ed-Din, to London. (Some sources translate the Shah's name as Nasser al-Din.) Twain wrote a series of five letters for the

Herald in June of 1873 reporting the visit of the Shah, the first Persian ruler to visit Europe. Other royalty present at the London reception for the Shah of Persia was Czar Alexander II's son and future ruler of Russia, Alexander III. Twain described seeing the future ruler of Russia:

...a young, handsome, mighty giant, in showy uniform, his breast covered with glittering orders, and a general's chapeau, with a flowing white plume, in his hand -- the heir to all the throne of all the Russians. The band greeted him with the Russian national anthem, and played it clear through. And they did right; for perhaps it is not risking too much to say that this is the only national air in existence that is really worthy of a great nation.

Twain further compared the future Russian Czar to the Shah of Persia:

We are certainly gone mad. We scarcely look at the young colossus who is to reign over 70,000,000 of people and the mightiest empire in extent which exists to-day. We have no eyes but for this splendid barbarian, who is lord over a few deserts and a modest ten million of ragamuffins -- a man who has never done anything to win our gratitude or excite our admiration, except that he managed to starve a million of his subjects to death in twelve months (1a).

Czar Alexander III (1845-1894)

He was at first admired by Mark Twain but was later on the receiving end of much of Twain's hostility towards Russian monarchy. Photo from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. |

_____

MARK TWAIN CHANGES HIS ATTITUDE

Alexander II's reforms which began with the 1861 emancipation of the serfs were not satisfactorily fulfilled. Peasants thought that they would be freed together with the plot of land they worked. Such was not the case. Although they were free, peasants were often denied an opportunity to purchase fertile land on which they had lived a lifetime. Instead many were offered poorer quality land that could not be farmed. Demands for a more democratic form of government and basic freedoms continued to be denied. When Alexander II was assassinated by a bomber in 1881 his son Alexander III succeeded him as Czar of Russia. Alexander III proved to be a more repressive monarch than his father.

As Mark Twain cultivated his career as a successful writer and lecturer, he became more keenly aware of world politics. Twain's attitude toward Russian monarchy shifted. Although Twain had devoted little attention to Russian politics between 1867 and 1881, a reading he delivered at the Hartford Monday Evening Club on March 22, 1886 indicates his opinion of the Russian aristocracy changed:

Power, when lodged in the hands of man, means oppression -- insures oppression: it means oppression always: … give it to the high priest of the Christian Church in Russia, the Emperor, and with a wave of his hand he will brush a multitude of young men, nursing mothers, gray headed patriarchs, gently young girls, like so many unconsidered flies, into the unimaginable hells of his Siberia, and go blandly to his breakfast, unconscious that he has committed a barbarity …(2).

_____

INFLUENCE OF GEORGE KENNAN

A continued hardening of Twain's attitude against the Russian aristocracy, and indeed most of America's, can be traced to a series of articles commissioned by Richard Watson Gilder, editor of

Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine.

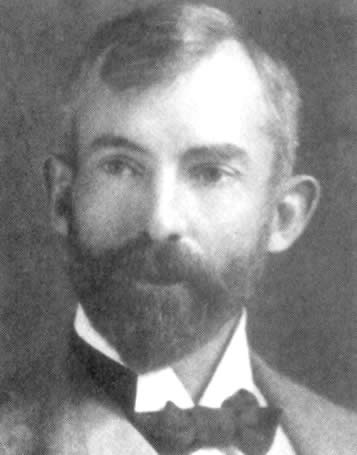

| Gilder hired American explorer and journalist George Kennan to travel to Siberia, a penal colony used for isolating Russians who voiced political opposition to the Czar. Kennan reported on the quality of life in the Siberian labor mining camps. Kennan's articles were published beginning in November 1887 and continued until April 1891. His reports in Century shocked Americans. Kennan returned to America a staunch supporter of a Russian revolution and traveled across the United States giving lectures accompanied by lantern slide shows which featured photographs of prisoners. |

George Kennan dressed as prisoner in Siberia. Photo from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division |

News reports indicate that Mark Twain was present at one of George Keenan's lectures as early as March 1888 and wept afterwards.

KANSAS CITY STAR, Saturday, April 7, 1888, p. 2.

When Mark Twain Wept.Washington Correspondent Philadelphia Record.

There was a very dramatic scene at the meeting of the Literary society last Saturday evening. The members and their guests, including many distinguished personages, had gathered in the drawing-room. Presently the company saw a strange figure clad in wretched clothes and fettered with heavy chains standing in the doorway. For a moment his friends did not recognize it as Mr. George Kennan, the vice-president of the society, who had promised to read them some letters from Russian state prisoners in Siberia. The costume, and especially the chains, greatly heightened the effect of the letters, heartrending as some them were, and touching as all of them were in themselves. The thought that some of these simple stories of suffering were written by just such a refined and cultivated man as Kennan himself, and others by women even more refined and cultivated, was strongly impressed upon every one.

"I feel completely unnerved," said Senator Hawley when Kennan had finished, and by so saying expressed the common thought. Mark Twain, who had actually been weeping, could not refrain from a more extended expression. Rising to his full height and speaking for once with seriousness, he said that were he a Russian he would be a revolutionist -- it would be inevitable. He might respect the czar as a man, but as a ruler he would destroy him. He believed that the moral power of the civilized world ought to be brought to bear upon Russia to put a speedy stop to such cruelties and outrages in the name of law.

|

The following report from the

Boston Daily Globe, February 26, 1889, p. 8 describes a typical Kennan lecture.

AUTOCRATIC RUSSIA

George Kennan's Lecture on Siberian Exiles.

Tears Fall as He Recites the Hardships of Political Convicts in the Mines.

Noble Self-Sacrifices by Those Whose Only Crime is Love of Country.

George Kennan's Siberian lecture in the Lowell Institute course delivered last evening was entitled "Political Convicts in the Mines." The profound interest in the subject taken by the well-informed and thinking people of Boston was attested in a marked manner by the crowd which attended last evening. Every foot of standing room in the aisles was occupied, some sat upon the window ledges, while others almost literally clung to the walls with their fingers and toes and a solid phalanx of ladies sat all around the edge of the rostrum, and though the regular seat-holders were considerable discomfited the delivery of the lectures was so satisfactory and the subject appealed so strongly to the tenderest feelings of everyone, that not a complaint or sign of dissatisfaction was shown.

The lecture was almost entirely devoted to giving sketches of the lives of famous revolutionists serving long sentences in the mines of Kara, where prisoners were chained to wheelbarrows which could not be removed even at night.

One unusually humane officer, touched by the terrible sufferings of men whose only offenses had been a zeal for their country's happiness, had released them from the wheelbarrow chains, giving them the free use of their limbs, but the governor general of Eastern Siberia hearing of it, had ordered them restored. The humane officer reluctantly notified his captives of the renewed sufferings he was commanded to inflict upon them, and gave them three days in which to prepare for the new order of things.

The kind-hearted officer, unable to stand the scenes of suffering, resigned his command with the hope that he might be transferred to some more congenial department; but was told by the governor general that such a man as he was unfit to hold any position under the government.

Terrible tragedies followed. Several men and women shot themselves, or drank poison made by soaking matches in water, while others became hopeless maniacs.

Brief and most tragic histories were related of the lives of the following prisoners at the prison of Kara, all of whom were refined and cultured men and women. Several of the notable families: Anna Pavlovan Korba, Mme. Kavalef Skayn, Dr. Edward Volmar, Mme. Yakimova and her child, and Eugene Semyanofski.

Impressive photographic portraits of all the characters referred to were thrown upon the screen and their strong and handsome features were gazed at by the large audience with an intense though sad interest.

The lecturer said that political prisoners on the way to Siberia are always photographed somewhere on the march, in order that if they escape their portraits may be sent in every direction, to aid in their capture; and the photographs which Mr. Kennan procured were got by bribing the photographers, who ran grave risks in parting with them.

Teams came to the eyes of many of the auditors at the recital of grievous incidents in the stories of the several unfortunates, and one of the most pathetic incidents mentioned was that of a little boy, born in prison of a noble captive mother, and who entertained the greatest fear of any man not wearing a soldier's uniform. The child knew no other life than that of the prison, and the only persons whom he had confidence in were the men who held his mother a prisoner.

He spoke to Mr. Kennan of his mother's life in the mines, and of his father's captivity in another prison 1000 miles away, and with smiling face and without any conception of any other existence.

Among the heart-rending incidents of life in the mines of Kara, was the description of hunger strikes by the women, who, in efforts to force the officers to allow them to associate together instead of being isolated, had abstained from eating, voluntarily starving themselves for 17 days upon one occasion, at the expiration of which time a physician was sent to them with appliances for injection and orders to force them to take sustenance. One of the women fell upon her knees and begged the physician by the memory of her mother, his sister and his wife, not to inflict upon them such an outrage. He was touched by her entreaties, and succeeded in so influencing the officers that the women won the strike after 17 days of fasting, and when they were so weak as to be hardly capable of doing anything for themselves.

Pictures of the prison were shown which appeared to be long one-story buildings, built like an ordinary log house. The internal arrangements consisting of a corridor running the full length of the building, with several large coils on each side, each one accommodating many prisoners. The rude windows look out upon a yard formed by the erection of a high stockade. The stockade is a recent adoption, brought about by a visiting inspector, who said grimly while looking from one of the windows out upon the street: "H'm, this prison is too much like a palace." So all view was shut off by the erection of the stockade.

One of the most profoundly interested and affected auditors present last evening was a Russian student at Harvard, who has a brother serving a sentence at Kara. The enthusiasm displayed during the lecture was in marked contrast to anything seen at the general run of lectures in the Lowell Institute course and every allusion to the noble self-sacrifice of the exiles in Siberia, and their efforts to establish a constitutional government in place of the present autocracy of the Czar was greeted with an electrical and rousing response.

The last lecture in the course will be given on Wednesday evening. |

Some sources indicate that Mark Twain attended one of Kennan's six lectures at Lowell Institute and afterwards, in a voice choked with tears, exclaimed "If such a government cannot be overthrown otherwise than by dynamite, then thank God for dynamite" (

3). With a steady stream of publicity in the

Century and Kennan's lectures, the American public came to accept assassination as an acceptable means of political reform in Russia.

_____

MARK TWAIN'S ATTITUDE SET IN INK

Anti-czarist comments in Twain's writings appear more frequently in Twain's work after George Kennan's publicity tours. In

Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven, a manuscript Twain worked on for over thirty years he compared heaven to Russia:

Well, this is Russia -- only more so. There's not the shadow of a republic about it anywhere (4).

Twain completed his novel

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court in April 1889. Mark Twain scholar Howard Baetzhold theorized that George Kennan's illustrated articles and his visual descriptions of Siberian exiles in the

Century were sources for the descriptions of slaves in

Connecticut Yankee (

4a).

Dan Beard's illustration of the Yankee and the King sold as slaves,

Dan Beard's illustration of the Yankee and the King sold as slaves,

from chapter 34, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.

Twain did not include the preface he had originally written for the book. It was published after Twain's death by his biographer Albert Bigelow Paine:

I have drawn no laws and no illustrations from the twin civilizations of hell and Russia. To have entered into that atmosphere would have defeated my purpose, which was to show a great and genuine progress in Christendom in these few later generations toward mercifulness -- a wide and general relaxing of the grip of the law. Russia had to be left out because exile to Siberia remains, and in that single punishment is gathered together and concentrated all the bitter inventions of all the black ages for the infliction of suffering upon human beings. Exile for life from one's hearthstone and one's idols -- this is rack, thumb-screw, the water-drop, fagot and stake, tearing asunder by horses, flaying alive -- all these in one; and not compact into hours, but drawn out into years, each year a century, and the whole a mortal immortality of torture and despair. While exile to Siberia remains one will be obliged to admit that there is one country in Christendom where the punishments of all the ages are still preserved and still inflicted, that there is one country in Christendom where no advance has been made toward modifying the medieval penalties for offenses against society and the State (5).

In November 1889 Brazil overthrew their monarch Dom Pedro in a bloodless revolution that was called "the most peaceful revolution of the century." The news delighted Twain and he expressed his continuing contempt for the remaining monarchs of Europe in a letter dated November 20, 1889 to Sylvester Baxter of the Boston

Herald:

DEAR MR. BAXTER -- Another throne has gone down, and I swim in oceans of satisfaction. I wish I might live fifty years longer; I believe I should see the thrones of Europe selling at auction for old iron. I believe I should really see the end of what is surely the grotesquest of all the swindles ever invented by man -- monarchy. It is enough to make a graven image laugh, to see apparently rational people, away down here in this wholesome and merciless slaughter-day for shams, still mouthing empty reverence for those moss-backed frauds and scoundrelisms, hereditary kingship and so-called "nobility." It is enough to make the monarchs and nobles themselves laugh -- and in private they do; there can be no question about that. I think there is only one funnier thing, and that is the spectacle of these bastard Americans -- these Hamersleys and Huntingtons and such -- offering cash, encumbered by themselves, for rotten carcases and stolen titles. When our great brethren the disenslaved Brazilians frame their Declaration of Independence, I hope they will insert this missing link: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all monarchs are usurpers, and descendants of usurpers; for the reason that no throne was ever set up in this world by the will, freely exercised, of the only body possessing the legitimate right to set it up -- the numerical mass of the nation."

You already have the advance sheets of my forthcoming book in your hands. If you will turn to about the five hundredth page, you will find a state paper of my Connecticut Yankee in which he announces the dissolution of King Arthur's monarchy and proclaims the English Republic. Compare it with the state paper which announces the downfall of the Brazilian monarchy and proclaims the Republic of the United States of Brazil, and stand by to defend the Yankee from plagiarism. There is merely a resemblance of ideas, nothing more. The Yankee's proclamation was already in print a week ago. This is merely one of those odd coincidences which are always turning up. Come, protect the Yank from that cheapest and easiest of all charges -- plagiarism. Otherwise, you see, he will have to protect himself by charging approximate and indefinite plagiarism upon the official servants of our majestic twin down yonder, and then there might be war, or some similar annoyance.

Have you noticed the rumor that the Portuguese throne is unsteady, and that the Portuguese slaves are getting restive? Also, that the head slave-driver of Europe, Alexander III, has so reduced his usual monthly order for chains that the Russian foundries are running on only half time now? Also that other rumor that English nobility acquired an added stench the other day -- and had to ship it to India and the continent because there wasn't any more room for it at home? Things are working. By and by there is going to be an emigration, may be. Of course we shall make no preparation; we never do. In a few years from now we shall have nothing but played-out kings and dukes on the police, and driving the horse-cars, and whitewashing fences, and in fact overcrowding all the avenues of unskilled labor; and then we shall wish, when it is too late, that we had taken common and reasonable precautions and drowned them at Castle Garden (5a).

Twain continued to vent his rage at the Russian regime in 1890 in writings that were not published until after his death. A mock communication from Alexander III is another example published by Paine after Twain's death.

ST. PETERSBURG, February.

COL. MARK TWAIN, Washington.

Your cablegram received. It should have been transmitted through my minister, but let that pass. I am opposed to international copyright. At present American literature is harmless here because we doctor it in such a way as to make it approve the various beneficent devices which we use to keep our people favorable to fetters as jewelry and pleased with Siberia as a summer resort. But your bill would spoil this. We should be obliged to let you say your say in your own way. Voila! my empire would be a republic in five years and I should be sampling Siberia myself.

If you should run across Mr. Kennan please ask him to come over and give some readings. I will take good care of him.

ALEXANDER III.

144 -- Collect (6)

In the summer of 1890 Twain wrote "The Answer," a manuscript not yet published outside of the microfilm edition of the Mark Twain Papers. It is a burlesque reply from Alexander III to "Impertinent Republican Scum" admitting the charges of which George Kennan has accused him and sneering at his foreign critics.

_____

AN UNSENT LETTER TO THE EDITOR OF FREE RUSSIA, 1890

In the summer of 1890 Twain also composed a letter which he never mailed to the editor of the publication

Free Russia which advocated Russian reforms. Twain's support of violence to overthrow the Czar along with his impatience with the Russian people for tolerating abuses was evident.

To the Editor of Free Russia,

I thank you for the compliment of your invitation to say something, but when I ponder the bottom paragraph on your first page, and then study your statement on your third page, of the objects of the several Russian liberation-parties, I do not quite know how to proceed. Let me quote here the paragraph referred to:

"But men's hearts are so made that the sight of one voluntary victim for a noble idea stirs them more deeply than the sight of a crowd submitting to a dire fate they cannot escape. Besides, foreigners could not see so clearly as the Russians how much the Government was responsible for the grinding poverty of the masses; nor could they very well realize the moral wretchedness imposed by that Government upon the whole of educated Russia. But the atrocities committed upon the defenceless prisoners are there in all their baseness, concrete and palpable, admitting of no excuse, no doubt or hesitation, crying out to the heart of humanity against Russian tyranny. And the Tzar's Government, stupidly confident in its apparently unassailable position, instead of taking warning from the first rebukes, seems to mock this humanitarian age by the aggravation of brutalities. Not satisfied with slowly killing its prisoners, and with burying the flower of our young generation in the Siberian desserts, the Government of Alexander III resolved to break their spirit by deliberately submitting them to a regime of unheard-of brutality and degradation."

When one reads that paragraph in the glare of George Kennan's revelations, and considers how much it means; considers that all earthly figures fail to typify the Czar's government, and that one must descend into hell to find its counterpart, one turns hopefully to your statement of the objects of the several liberation-parties -- and is disappointed. Apparently none of them can bear to think of losing the present hell entirely, they merely want the temperature cooled down a little.

I now perceive why all men are the deadly and uncompromising enemies of the rattlesnake: it is merely because the rattlesnake has not speech. Monarchy has speech, and by it has been able to persuade men that it differs somehow from the rattlesnake, has something valuable about it somewhere, something worth preserving, something even good and high and fine, when properly "modified," something entitling it to protection from the club of the first comer who catches it out of its hole. It seems a most strange delusion and not reconcilable with our superstition that man is a reasoning being. If a house is afire, we reason confidently that it is the first comer's plain duty to put the fire out in any way he can -- drown it with water, blow it up with dynamite, use any and all means to stop the spread of the fire and save the rest of the city. What is the Czar of Russia but a house afire in the midst of a city of eighty millions of inhabitants? Yet instead of extinguishing him, together with his nest and system, the liberation-parties are all anxious to merely cool him down a little and keep him.

It seems to me that this is illogical -- idiotic, in fact. Suppose you had this granite-hearted, bloody-jawed maniac of Russia loose in your house, chasing the helpless women and little children -- your own. What would you do with him, supposing you had a shotgun? Well, he is loose in your house -- Russia. And with your shotgun in your hand, you stand trying to think up ways to modify" him.

Do these liberation-parties think that they can succeed in a project which has been attempted a million times in the history of the world and has never in one single instance been successful -- the "modification" of a despotism by other means than bloodshed? They seem to think they can. My privilege to write these sanguinary sentences in soft security was bought for me by rivers of blood poured upon many fields, in many lands, but I possess not one single little paltry right or privilege that come to me as a result of petition, persuasion, agitation for reform, or any kindred method of procedure. When we consider that not even the most responsible English monarch ever yielded back a stolen public right until it was wrenched from them by bloody violence, is it rational to suppose that gentler methods can win privileges in Russia?

Of course I know that the properest way to demolish the Russian throne would be by revolution. But it is not possible to get up a revolution there; so the only thing left to do, apparently, is to keep the throne vacant by dynamite until a day when candidates shall decline with thanks. Then organize the Republic. And on the whole this method has some large advantages; for whereas a revolution destroys some lives which cannot well be spared, the dynamite way doesn't. Consider this: the conspirators against the Czar's life are caught in every rank of life, from the low to the high. And consider: if so many take an active part, where the peril is so dire, is this not evidence that the sympathizers who keep still and do not show their hands, are countless for multitudes? Can you break the hearts of thousands of families with the awful Siberian exodus every year for generations and not eventually cover all Russia from limit to limit with bereaved fathers and mothers and brothers and sisters who secretly hate the perpetrator of this prodigious crime and hunger and thirst for his life? Do you not believe that if your wife or your child or your father was exiled to the mines of Siberia for some trivial utterances wrung from a smarting spirit by the Czar's intolerable tyranny, and you got a chance to kill him and did not do it, that you would always be ashamed to be in your own society the rest of your life? Suppose that that refined and lovely Russian lady who was lately stripped bare before a brutal soldiery and whipped to death by the Czar's hand in the person of the Czar's creature had been your wife, or your daughter or your sister, and to-day the Czar should pass within reach of your hand, how would you feel -- and what would you do? Consider, that all over vast Russia, from boundary to boundary, a myriad of eyes filled with tears when that piteous news came, and through those tears that myriad of eyes saw, not that poor lady, but lost darlings of their own whose fate her fate brought back with new access of grief out of a black and bitter past never to be forgotten or forgiven.

If I am a Swinburnian -- and clear to the marrow I am -- I hold human nature in sufficient honor to believe there are eighty million mute Russians that are of the same stripe, and only one Russian family that isn't.

Mark Twain (7).

_____

REVISED CHRISTMAS GREETINGS, 1890

When asked to contribute a Christmas greeting that could be published in newspapers at the end of December 1890, Twain composed the following which appeared in the

Boston Daily Globe on December 25, 1890:

Boston Daily Globe, December 25, 1890, p. 3

CHRISTMAS GREETINGS

...

Mark Twain

It is my heart-warm and world-embracing Christmas hope and aspiration that all of us, the high, the low, the rich, the poor, the admired, the despised, the loved, the hated, the civilized, the savage, may eventually be gathered together in a heaven of everlasting rest and peace and bliss, escape [sic] the inventor of the telephone.

MARK TWAIN.

Hartford, Dec. 23

|

Twain was later quoted as saying:

I had no intention of reflecting on the inventor of the telephone when I started to write. I intended to wish everyone a Happy New Year, with the exception of the Emperor of Russia …Just then the telephone rang … and I went to the telephone and, as usual, lost my temper … I hung up the telephone in disgust and went back to my writing, and instead of the Emperor of Russia I put in the inventor of the telephone (8).

An unpublished version of the quote "extends a Merry Christmas to all deserving people while remanding others to the arms of Satan or the Emperor of Russia, according to their preference" (

9).

_____

"LETTERS FROM A DOG," JANUARY - FEBRUARY 1891

In an essay not published in his lifetime, Twain wrote "Letters from a Dog to Another Dog Explaining and Accounting for Man" in the early months of 1891. Decrying the brutal nature of man and monarchy, Mark Twain denounced the Russian czar as an example.

Consider the Czar of Russia. His powers are a theft to-day, just as they were when they came originally into his family. His portrait hangs everywhere that you may go, throughout his dominions. His eighty million slaves, instead of being privileged to clod it with mud wherever they find it, and say "This is the posterity of that highwayman that robbed our fathers," are actually required to take their hats off when they come into its presence, and humbly salute it. ... The Czar requires every Russian to spend the fifteen best and most efficient years of his life in the army; and then turns him adrift without pension and ignorant of all ways of sustaining life except by killing people. (9a)

"Letters from a Dog to Another Dog Explaining and Accounting for Man" was first published in print in 2009 and included in

Mark Twain's Book of Animals(University of California Press) and provides further evidence that Mark Twain's animosity to the Russian government permeated those essays he chose never to print..

_____

STEPNIAK'S VISIT, APRIL 1891

The publication

Free Russia was first established in England in 1890 by the English Friends of Russian Freedom in coordination with Russian revolutionary Sergei Kravchinski, an author who advocated political terrorism. Kravchinski had killed the Russian chief of secret police in St. Petersburg in 1878. After leaving Russia, he eventually settled in London and wrote under the name of Sergius Stepniak. By the 1880s English translations of his books were published by Harper and Brothers and other prominent American publishing houses. In November 1888, Twain's colleague William Dean Howells had written a favorable review of Stepniak's

The Russian Peasant. In 1891 when Stepniak traveled to Boston seeking additional support from Americans for the Russian revolution he visited with Howells. Howells, in turn, provided him with a letter of introduction to Mark Twain. Stepniak visited Twain in April 1891.

By the end of April, Stepniak had succeeded in organizing the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom and an American edition of

Free Russia began publication in July 1891. Along with Mark Twain, other the prominent members of the American Society were Lyman Abbot, Alice Stone Blackwell, William Lloyd Garrison, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Julia Ward Howe, George Kennan, James Russell Lowell, Hamilton W. Mabie, Alice Freeman Palmer and Frank B. Sanborn. George Kennan translated documents for

Free Russia and Alice Blackwell served as head of the news bureau (

10). Stepniak returned to London by the end of 1891 where he was killed in a train accident a few years later on December 23, 1895.

_____

THE AMERICAN CLAIMANT, 1891

Coinciding with the visit of Stepniak in early 1891 was Twain's work on

The American Claimant. The book is peppered with references to Siberia and Russian tyranny. In chapter 18 Twain has his protagonist Colonel Sellers proposing to buy Siberia:

Where is the place where there is twenty-five times more manhood, pluck, true heroism, unselfishness, devotion to high and noble ideals, adoration of liberty, wide education, and brains, per thousand of population, than any other domain in the whole world can show?"

"Siberia!"

"Right."

"It is true; it certainly is true, but I never thought of it before."

"Nobody ever thinks of it. But it's so, just the same. In those mines and prisons are gathered together the very finest and noblest and capablest multitude of human beings that God is able to create. Now if you had that kind of a population to sell, would you offer it to a despotism? No, the despotism has no use for it; you would lose money. A despotism has no use for anything but human cattle. But suppose you want to start a republic?"

"Yes, I see. It's just, the material for it."

"Well, I should say so! There's Siberia with just the very finest and choicest material on the globe for a republic, and more coming -- more coming all the time, don't you see! It is being daily, weekly, monthly recruited by the most perfectly devised system that has ever been invented, perhaps. By this system the whole of the hundred millions of Russia are being constantly and patiently sifted, sifted, sifted, by myriads of trained experts, spies appointed by the Emperor personally; and whenever they catch a man, woman or child that has got any brains or education or character, they ship that person straight to Siberia. It is admirable, it is wonderful. It is so searching and so effective that it keeps the general level of Russian intellect and education down to that of the Czar" (11).

The American Claimant was serialized in the Sunday edition of the

New York Sun in early 1892 and in various McClure syndications as well as England's

Idler.

_____

TOM SAWYER ABROAD, 1892

In June 1891 financial reverses forced Twain to close his home in Hartford, Connecticut and move to Europe with his family. His notebooks from that time period contain occasionally references to Russia. One September 9, 1891 he wrote:

The idiotic Crusades were gotten up to 'rescue' a valueless tomb from the Saracens. It seems to me that a crusade to make a bonfire of the Russian throne & fry the Czar in it wd have some sense (12).

In 1892, Twain, living in Germany at the time, responded to an offer from Mary Mapes Dodge to write a story for

St. Nicholas Magazine. Twain completed "Tom Sawyer Abroad" in the fall of 1892. His impatience with the Russian population's inability to overthrow the Czar was evident in that story:

And look at Russia. It spreads all around and everywhere, and yet ain't no more important in this world than Rhode Island is, and hasn't got half as much in it that's worth saving (13).

_____

EXTRADITION TREATY WITH RUSSIA 1893

In February 1893 the United States Congress passed a controversial extradition treaty with Russia which made the attempted assassination of the Czar or his members of his family a nonpolitical crime. Russia had lobbied for the treaty since 1886. Many Americans opposed this extradition treaty on the grounds that it threatened Russian political exiles who had sought refuge in the United States. Russian revolutionaries seeking asylum in the United States were in danger of being extradited. The Society of the American Friends of Russian Freedom opposed the treaty without success and the American edition of

Free Russia ceased publication in July 1894.

_____

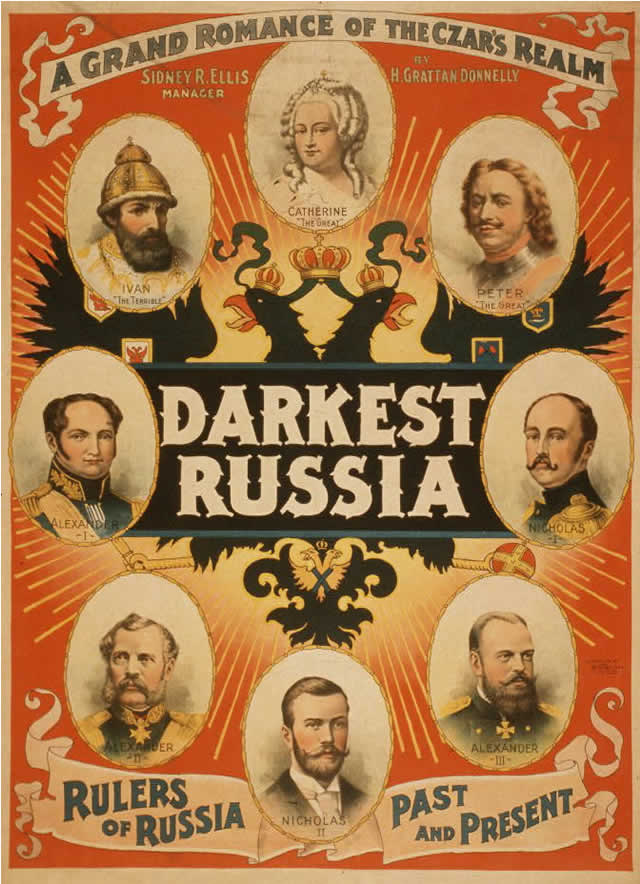

"DARKEST RUSSIA"

In the latter half of the 1890s the American public continued to be reminded of Russian despotism through various media. In January 1894 the play "Darkest Russia" by Henry Grattan Donnelly began playing in New York. The play featured scenes in a St. Petersburg palace, Nihilists headquarters, and a Siberian exile station. The plot of the play revolved around the arrest and transportation to Siberia of innocent persons present at a revolutionary gathering. A reviewer for the

New York Timesdescribed it as a "fine old melodrama of the blood-curdling sort" (

14).

Poster from the play "Darkest Russia" from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Poster from the play "Darkest Russia" from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

In November 1894, Czar Alexander III died from kidney disease and his son Nicholas II became Czar. Some Americans were willing to take a "wait and see" attitude regarding Nicholas II until it became apparent no democratic reforms would be forthcoming. The advertising posters for "Darkest Russia" featured Nicholas II's portrait in 1895 -- an indication that American expectations for quick reforms had died. "Darkest Russia" played on American stages through at least 1904.

In 1898 Mark Twain and his family were living in Vienna, Austria. On October 30, 1898, the

Philadelphia Inquirer, along with other American newspapers, featured a report datelined London, October 29, reporting that Mark Twain was planning a visit to St. Petersburg. A newspaper of that city, the

Petersburg Skylistokannounced that several humorists of St. Petersburg were preparing to celebrate his visit with a banquet. The visit never materialized.

_____

TWAIN'S CONTINUING RANDOM SHOTS AT RUSSIA, 1900-1902

Mark Twain and his family returned to the United States in October 1900. Twain's next public swing at Russia came in a speech delivered at the annual meeting of the

New York Public Education Association on November 23, 1900. Twain's speech was filled with anti-imperialistic sentiments and he complained that Russia had 30,000 soldiers in Manchuria who should be sent back home to farms to live in peace. He concluded that the New York Public Education Association was "much wiser in its day and generation than the Emperor of Russia and all his people" (

15).

Twain continued to criticize Russia for imperialistic expansion in Manchuria at least twice more before the end of 1900. In a speech given on

December 12, 1900 while introducing Winston Churchill at the Waldorf Astoria in New York he criticized both Britain and the United States saying:

We both stood timorously be at Port Arthur and wept sweetly and sympathizingly and shone while France and Germany helped Russia to rob the Japanese (16).

In

"A Salutation Speech from the Nineteenth Century to the Twentieth," published in the

New York Herald on December 30, 1900 Twain again criticized Russia's "pirate raids in Manchuria."

In his essay "To the Person Sitting in Darkness," published in the February 1901 issue of

North American Review he wrote of Russia:

…she seizes Manchuria, raids its villages, and chokes its great river with the swollen corpses of countless massacred peasants ...(17).

Also written about the same time as "To the Person Sitting in Darkness" was an essay titled "The Stupendous Procession" which was not published in Twain's lifetime. For a parade of countries in the twentieth century, Twain described Russia:

Weary Column of Exiles - Women, Children, Students, Statesmen, Patriots, stumbling along in the snow;

Mutilated Figure in Chains, labeled "Finland"

Floats piled with Bloated Corpses - Massacred Manchurian peasants (18)

Twain's short story "The Belated Russian Passport" was published in

Harper's Weekly on December 6, 1902. The story features a young man undergoing anxiety attacks as he is fears expulsion to Siberia if he cannot produce a passport while traveling to St. Petersburg.

In a few hours I shall be one of a nameless horde plodding the snowy solitudes of Russia, under the lash, and bound for that land of mystery and misery and termless oblivion, Siberia! I shall not live to see it; my heart is broken and I shall die (19).

_____

RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR AND "THE CZAR'S SOLILOQUY"

In February 1904 the Russo-Japanese war broke out, brought about by Russia's attempts to maintain a warm water seaport in the south of Manchuria. Japan mounted successful defeats of the Russian army and confidence in Czar Nicholas II's leadership continued to decline in Russia.

Czar Nicholas II (1868-1918)

Leader of Russia during the Russo-Japanese War was in power when Twain wrote "The Czar's Soliloquy" which advocated assassination of the Czar and his family.

Photo from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. |

Mark Twain and his family were living in Italy in 1904. William Lyon Phelps recalls visiting with him on April 14, 1904:

He was 68 years old, but looked older; his wife was desperately ill and indeed died in this villa Sunday 5 June. During this hour's interview, Mark smoked three cigars; there was a constant twitching in his right cheek and his right eye seemed inflamed. He was excited about the Russo-Japanese War, and was an intense partisan of the Japanese. I told him that Edith M. Thomas had published a poem calling on Americans to support the Russians because they were Christians and the Japanese heathens; and he replied, 'Edith doesn't know what she's talking about.' He pretended to believe the Russians had made a fatal error and shown lack of judgement in not sending a sufficient number of ikons with their soldiers. 'Why,' speaking with great emphasis, 'I read that they have sent out only eighty holy images with their troops! General Kuropatkin ought to have carried at least 800!' (19a)

On January 22, 1905 Russian laborers marched with a petition for reforms to the Czar's Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. In a skirmish with police and Cossack guards, over one hundred workers were killed and three hundred wounded. The incident was headlined around the world and became known in history as "Bloody Sunday." American journalists such as William English Walling, grandson of William Hayden English, Unites States Vice Presidential candidate in 1880; Samuel S. McClure, founder of

McClure's Magazine; Arthur Bullard, and Ernest Poole went abroad to cover the Russian revolution for American magazines and newspapers.

On January 23,

The New York Times reported, "The blood which crimsoned the snow has fired the brains and passions of the strikers and turned women as well as men into wild beasts, and the cry of the infuriated populace is for vengeance." The same article quoted Maxim Gorky, the Russian novelist, "To-day inaugurated revolution in Russia. The Emperor's prestige will be irrevocably shattered by the shedding of innocent blood. He has alienated himself forever from his people" (

20).

Mark Twain had returned to America after his wife's death. His response to the "Bloody Sunday" massacres was an essay titled "The Czar's Soliloquy" which he dated February 2, 1905. It was published in the

North American Review the following month March 1905. In the sketch Twain strikes out at moralists who have not supported assassination of the royal family:

A strange thing, when one considers it: to wit, the world applies to Czar and System the same moral axioms that have vogue and acceptance in civilized countries! Because, in civilized countries, it is wrong to remove oppressors otherwise than by process of law, it is held that the same rule applies in Russia, where there is no such thing as law -- except for our Family. Laws are merely restraints -- they have no other function. In civilized countries they restrain all persons, and restrain them all alike, which is fair and righteous; but in Russia such laws as exist make an exception -- our Family. We do as we please; we have done as we pleased for centuries. Our common trade has been crime, our common pastime murder, our common beverage blood -- the blood of the nation. Upon our heads lie millions of murders. Yet the pious moralist says it is a crime to assassinate us. We and our uncles are a family of cobras set over a hundred and forty million rabbits, whom we torture and murder and feed upon all our days; yet the moralist urges that to kill us is a crime, not a duty (21).

Twain's original manuscript indicates he was much more vehement in his call for assassination of the Czar than his published version. He urges Russian mothers to teach their children:

When you grow up, knife a Romanoff wherever you find him, loyalty to these cobras is treason to the nation; be a patriot, not a prig - set the people free (22).

Twain also wrote another manuscript which he first titled "A Difficult Conundrum" and later changed to "Flies and Russians" about the same time he wrote "The Czar's Soliloquy." An examination of the original manuscripts indicate that he may have intended to combine the two manuscripts into one but later changed his mind. "Flies and Russians" was not published during his lifetime. It was later published in 1972 in the collection Mark Twain's

Fables of Man. In "Flies and Russians" Twain shows his impatience with the Russian people who appear to be too cowardly to obtain their independence and to a creator who made them.

We have the flies and the Russians, we cannot help it, let us not bemoan about it, but manfully accept the dispensation and do the best we can with it. Time will bring relief, this we know, for we have history for it. Nature had made many and many a mistake before she added flies and Russians, and always she corrected them as soon as she could. She will correct this one too -- in time. Geological time.

Twain concluded this manuscript by adding:

Even in our own day Russians could be made useful if only a way could be found to inject some intelligence into them. How magnificently they fight in Manchuria! With what indestructible pluck they rise up after the daily defeat, and sternly strike, and strike again! how gallant they are, how devoted, how superbly unconquerable! If they would only reflect! if they could only reflect! if they only had something to reflect with! Then these humble and lovable slaves would perceive that the splendid fighting-energy which they are wasting to keep their chipmunk on the throne would abolish both him and it if intelligently applied (23).

In latter May and early June 1905 the New York papers reported on Japan's successful naval battles against the Russians under the leadership of Admiral Togo. The Russian naval fleet was destroyed in the battle of Tsushima on May 27. The news delighted Twain who wrote to his friend Joseph Twichell:

Togo forever! I wish somebody would assassinate the Russian Family. So does every sane person in the world - but who has the grit to say so? Nobody … (24).

_____

A JAB AT PRAYING FOR RUSSIAN VICTORIES AND CHRISTIAN SCIENCE

In June 1905 Mark Twain was writing on a manuscript titled No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger. He took the opportunity of the Russian naval defeat to ridicule Christians who had prayed for a Russian victory. Mary Baker Eddy, founder of the Christian Science movement published a telegram to her followers which was widely published in American newspapers:

Here, O Israel, the Lord God is one Lord.

I now request that the members of my Church cease special prayer for the peace of nations, and cease in full faith that God does not hear our prayers only because of oft speaking; but that He will bless all the inahbitants of the earth, and 'none can stay His hand nor say unto Him what doest thou.' Out of His allness He must bless all with His own truth and love.

MARY BAKER G. EDDY.

Pleasant View, Concord, N.H., June 27, 1905. |

Twain ridiculed Eddy's telegram refering to her as the founder of "Christian Silence." Criticizing the wording of her telegram, Twain wrote:

Down to the word 'nations' anybody can understand it. There's been a prodigious war going on for about seventeen months, with destruction of whole fleets and armies, and in seventeen words she indicates certain things, to-wit: I believed we could squelch the war with prayer, therefore I ordered it; it was an error of Mortal Mind, whereas I had supposed it was an inspiration; I now order you to cease from praying for peace and take hold of something nearer our size, such as strikes and insurrections.... It seems to mean that He does not listen to our prayers any more because we pester Him too much. This carries us to the phrase of 'oft-speaking.' At that point the fog shuts down, black and impenetrable, it solidifies into uninterpretable irrelevances. Now then, you add up, and get these results: the praying must be stopped -- which is clear and definite; the reason for the stoppage is -- well, uncertain. ... If you put part of the message in school-girl and the rest in Choctaw, the interpreter is going to be defeated, and colossal harm can come of it. ... What is His allness?" ... It probably means that she entered the game because she thought only His halfness was in it and would need help; then perceiving that His allness was there and playing on the other side, she considered it best to cash-in and draw out. I think that must be it; it looks reasonable, you see, because in seventeen months she hadn't put up a single chip and got it back again, and so in the circumstances it would be natural for her to want to go out and see a friend (24a).

_____

TREATY OF PORTSMOUTH 1905

United States President Theodore Roosevelt mediated a peace settlement of the Russo-Japanese War in late August 1905 at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. When the peace settlement had been reached, the

Boston Globe telegraphed prominent Americans asking for their reaction. Mark Twain's response, published by the

Globe on August 30, 1905, was a dissenting voice among the numerous congratulations. Twain was summering in Dublin, New Hampshire at the time and transmitted the following response:

DURHAM, N. H., Aug 29 -- To the Editor of the Globe:

Russia was on the high road to emancipation from an insane and intolerable slavery; I was hoping there would be no peace until Russian liberty was safe. I think that this was a holy war in the best and noblest sense of that abused term, and that no war was ever charged with a higher mission; I think there can be no doubt that that mission is now defeated and Russia's chains re-riveted, this time to stay.

I think the czar will now withdraw the small humanities that have been forced upon him, and resume his medieval barbarisms with a relieved spirit and an immeasurable joy. I think Russian liberty had had its last chance, and has lost it.

I think nothing has been gained by the peace that is remotely comparable to what has been sacrificed by it. One more battle would have abolished the waiting chains of billions upon billions of unborn Russians, and I wish it could have been fought.

I hope I am mistaken, yet in all sincerity I believe that this peace is entitled to rank as the most conspicuous disaster in political history.

MARK TWAIN (25)

Twain would later recall, "No one in all this nation except Doctor Seaman and myself uttered a public protest against this folly of follies" (

26). Dr. Louis Livingston Seaman, a military doctor and surgeon who had recently spent six months in Manchuria had also refused to add his voice to the praise given to President Roosevelt. Seaman felt that the peace settlement would only allow Russia to recuperate sufficiently for another future struggle towards imperialism in the direction of China and the Pacific coast. Dr. Seaman's anti-imperialist views reflected many also held by Twain (

27).

The Treaty of Portsmouth was signed September 5, 1905. As a result, Japan received concessions and came to be recognized as a world power. Czar Nicholas II, in turn, was once again able to refocus on his own domestic problems. President Theodore Roosevelt was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for engineering an end to the hostilities.

Detail of postcard from the 1905 Portsmouth Conference

Detail of postcard from the 1905 Portsmouth Conference

from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

When political journalist Colonel George Harvey invited Twain to dinner with the Russian representatives to the Portsmouth conference, Twain carefully composed two telegrams before finally settling on a third version which he knew would be acceptable.

Dublin, N.H.

September 5, 1905

TO COLONEL HARVEY. - I am still a cripple, otherwise I should be more than glad of this opportunity to meet those illustrious magicians who with the pen have annulled, obliterated and abolished every high achievement of the Japanese sword and turned the tragedy of a tremendous war into a gay and blithesome comedy. If I may, let me in all respect and honor salute them as my fellow-humorists, I taking third place, as becomes one who was not born to modesty, but by diligence and hard work is acquiring it.

MARK.

~~~~~

Dublin, N.H.

September 5, 1905

DEAR COLONEL. -- No, this is a love-fest; when you call a lodge of sorrow send for me.

~~~~~

Twain finally sent Harvey the following third version of his response. Author and Twain biographer Van Wyck Brooks argued that the rewording was evidence that Twain suppressed opinions in order to cater to public opinion. Other scholars such as Louis J. Budd have found the wording to be ironic and ambiguous.

Dublin, N.H.

September 5, 1905

TO COLONEL HARVEY. -- I am still a cripple, otherwise I should be more than glad of this opportunity to meet the illustrious magicians who came here equipped with nothing but a pen, and with it have divided the honours of the war with the sword. It is fair to presume that in thirty centuries history will not get done admiring these men who attempted what the world regarded as impossible and achieved it.

MARK TWAIN.

Harvey later reported that Twain's response pleased the Russians and his response would be hand delivered to the Czar (

28).

A few months later Twain met with reporters when he was visiting in Boston with stockbroker Sumner B. Pearmain. On the subject of Russia, the

Boston Journal of November 6, 1905 quoted Twain:

I was really sorry when I heard there was to be peace between Russia and Japan. I thought if there was another battle the dissatisfaction would be so strong at home the government would have to give in to freedom. A few days ago when I read a constitution had been granted I began to think I had been too hasty, but now I don't feel so sure of it. As long as the army, and navy, and treasury are in the hands of the Czar the constitution don't amount to anything; nothing is accomplished today. … The Czar is in a hole, but not a bottomless hole. He's only waiting for a few years till the people get pacified and then he'll take back, one by one, the things he has doled out. Russia is a country by itself. When it talks about honor it is like any other pauper talking about money (29).

Twain continued to lend his support to causes supporting Russian freedom. In a

Thanksgiving message published in November 1905 Mark Twain theorized how God would view a recent Russian massacre of 50,000 Jews. In December 1905 when New York society leaders held a benefit for the aid of Jewish victims of the failed Russian revolution earlier in the year, Twain shared the honor of headlining the event along with actress Sarah Bernhardt. However,

Twain's speech for the event was light and humorous and made no mention of atrocities committed by the ruling aristocracy.

After the Treaty of Portsmouth was signed Czar Nicholas II promised constitutional reforms and elections but his efforts failed to appease the Russian revolutionaries.

_____

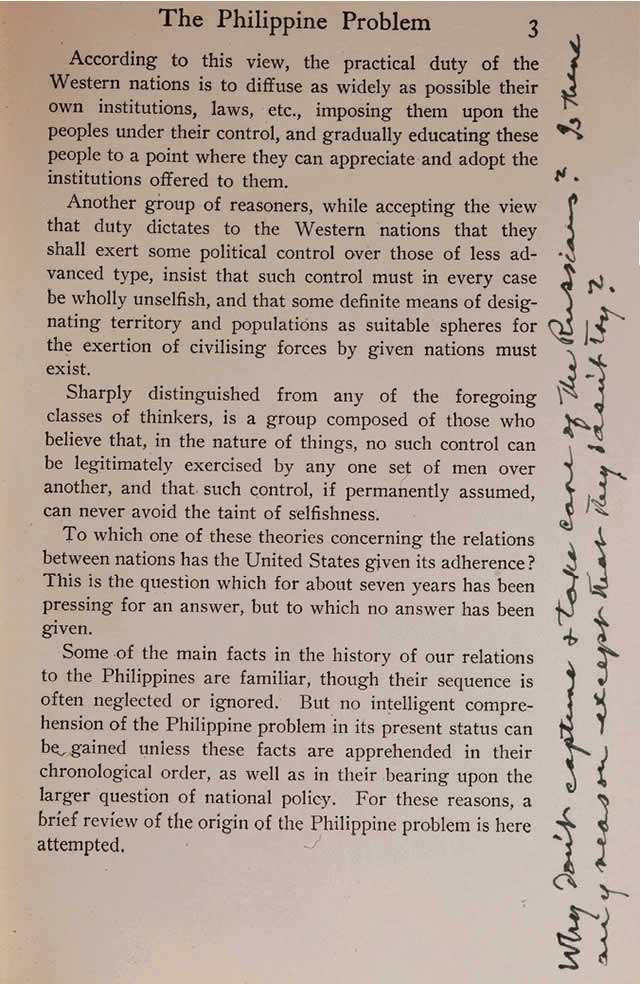

PARELLELS TO OUR PHILIPPINE PROBLEM: A STUDY OF AMERICAN COLONIAL POLICY - 1905

In 1905 Henry Parker Willis published

Our Philippine Problem: A Study of American Colonial Policy and discussed the views of colonialism and the obligations and duties of civilized countries to exert political control over countries in less advances stages of development. Twain received a copy of the book from Charles Francis Adams. In the margin of page 3 wrote, "Why don't [they] capture & take care of the Russians? Is there any reason except that they dasn't try?"

Mark Twain's copy of Our Philippine Problem where he wrote his thoughts on taking care of the Russians.

Mark Twain's copy of Our Philippine Problem where he wrote his thoughts on taking care of the Russians.

_____

THE "A CLUB" - 1906

Mark Twain's involvement in what eventually became the Maxim Gorky public calamity began on March 27, 1906 when Charlotte Teller came knocking on his front door. Twain was residing at 21 Fifth Avenue in New York, only a few hundred yards from Washington Square. His house was on the corner of Fifth Avenue and Ninth Street. Teller, the niece of United States Senator from Colorado Henry Moore Teller and daughter of Colorado attorney James Harvey Teller, was an attractive thirty-year-old writer who lived at 3 Fifth Avenue, about a block away. |

Charlotte Teller,

Mark Twain's neighbor on Fifth Avenue.

Photo courtesy of Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. |

The old mansion at 3 Fifth Avenue where Teller lived housed a group of writers that newspapers had tagged the "A Club." The label was based on a quip writer Howard Brubaker had given when a reporter once asked him for the name of the group. Brubaker had replied, "Oh, just call it a club" (

30). Residents of the house shared in its operating expenses. A dining room was located in the basement, a music room on the first floor, a writing area on the second floor, and on the top two floors were living quarters (

31).

Most of the writers were active members of the socialist movement in the United States. Author Ernest Poole provides one of the best descriptions of life inside 3 Fifth Avenue:

We were known as the A Club. Brubaker, Walter Weyl and I, Leroy Scott and Miriam his wife, Mary Heaton and Burt Vorse [Albert White Vorse], Bob and Martha Bruere, Charlotte Teller and several others were there. With most of us writing books, stories or plays, and all of us dreaming of reforms and revolutions of divers kinds, life in that house was a quick succession of intensities, large and small, from tremendous discussions about the world to hot little personal feuds and disputes; but through it all ran a broad fresh river of genial humor and relish in life. On warm spring evenings some of us sat out on the stoop on Fifth Avenue, sipping mint juleps brought from the old Brevoort Cafe… Charlotte Teller was a good friend of Mark Twain and, from his house around the corner, often he's stroll over, in his white suit with his great shock of snowy hair, sit down by the fireplace, light a cigar and drawl stories to our admiring group. Why did we admire him? Because beneath his good-humored jibes at all radical theories and creeds we could feel him a rebel like ourselves, and because he was a giant, and because he could tell stories as we'd never heard them told before (32).

Teller later recalled her first encounter with Mark Twain:

…word came to a group of us who were living at 3 Fifth Ave, all of us writers, that Tschaikowsky was coming with Gorki to raise money in the U. S. When he arrived I saw him, and found him much depressed because he did not know how to reach Mark Twain, whom he wanted as chairman for a big mass meeting. Although I did not know Mark Twain myself, I offered to see what could be done. I went to 21 Fifth Ave. and asked for Mr. Clemens's secretary. She said to bring Tschaikowsky back at 2 o'clock in the afternoon. I did, and introduced the two men, both of them white haired and most distinguished in appearance (33).

Teller, who was once married to Washington, D.C. civil engineer, Frank Minitree Johnson, introduced herself to Twain and his secretary Isabel Lyon as Mrs. Johnson. Isabel Lyon recorded in her personal journal

A young and delightfulish Mrs. Johnson came in yesterday to ask if Mr. Clemens would care to meet Mr. Tschaykoffski, the Russian Revolutionary agitator. He came and Mr. Clemens had a good talk with him, but discouraged him a bit I fear. Mrs. Johnson herself is a clever creature, I believe, for she attracts you and she told me how for a year she has been working on a Joan of Arc play for Maude Adams (34).

_____

MEETING NIKOLAI TCHAYKOVSKY

Nikolai Tchaykovsky whose name has been variously spelled Nicholas Tchaikovsky, Tschaikovsky, Chaykovsky, Chaikovsky, Schaykovsky and Tschaykoffski in news reports, letters and private journals will be spelled "Tchaykovsky" throughout this document (unless the reference is in a direct quotation) in order to conform to the way he spelled his own name.

Tchaykovsky, born in St. Petersburg about 1842 into a well-to-do family, was educated to be a teacher and taught school for a number of years in Russia. In the early 1870s he became involved in the Russian revolutionary movement and was sentenced to exile in Siberia in 1875. Prior to his exile he escaped Russia and made his way to London. He came to America about 1878 and helped organized a small Russian Socialistic colony near Cedar Vale, Kansas. He later returned moved to Philadelphia where he worked in the shipyards. From there he moved to Mount Morris, New York with a Shaker colony and then returned to Europe. Living in Harrow near London with a wife and three children, Tchaykovsky supported himself by teaching (

35).

Tchaykovsky had come to the United States in 1906 to conduct a fund raising effort for arms to equip Russian revolutionaries seeking to overturn the Czar. Tchaykovsky was also laying the groundwork for the April 1906 arrival in the United States of Maxim Gorky. Gorky, the pen name of Alexai Maximovich Peshkov, born in 1868, represented a younger generation of Russian revolutionaries. His pen name, when translated into English meant "Bitter One." Americans had become familiar with Gorky's writings and his news reports which depicted Russian suffering on "Bloody Sunday" 1905. Between January 1901 and March 1906,

The New York Times had printed over 200 stories related to Maxim Gorky. After being arrested for anti-Czarist writings after the 1905 revolt many American journals including

Scribner's,

Century, and

Harper's had protested the reports that Gorky would be hung and they joined an outcry for his release from prison. Gorky escaped execution in Russia but he was told to leave the country. Before leaving Russia he contacted American journalist William English Walling who provided him with letters of introduction to his friends at the "A Club."

In early February 1906 the volcano Mt. Vesuvius in Naples, Italy began erupting and throughout the following weeks Twain's writings and dictation made comparisons to what was happening around him to the Vesuvius eruption. Three days after meeting with Tchaykovsky, Twain dictated for his autobiography the following passage on March 30, 1906:

Three days ago a neighbor brought the celebrated Russian revolutionist, Tchaykoffsky, to call upon me. He is grizzled, and shows age -- as to exteriors -- but he has a Vesuvius, inside, which is a strong and active volcano yet. He is so full of belief in the ultimate and almost immediate triumph of the revolution and the destruction of the fiendish autocracy, that he almost made me believe and hope with him. He has come over here expecting to arouse a conflagration of noble sympathy in our vast nation of eighty millions of happy and enthusiastic freemen. But honesty obliged me to pour some cold water down his crater. I told him what I believed to be true: that our Christianity which we have always been so proud of -- not to say so vain of -- is now nothing but a shell, a sham, a hypocrisy; that we have lost our ancient sympathy with oppressed peoples struggling for life and liberty; that when we are not coldly indifferent to such things we sneer at them, and that the sneer is about the only expression the newspapers and the nation deal in with regard to such things; that his mass meetings would not be attended by people entitled to call themselves representative Americans, even if they may call themselves Americans at all; that his audiences will be composed of foreigners who have suffered so recently that they have not yet had time to become Americanized and their hearts turned to stone in their breasts; that these audiences will be drawn from the ranks of the poor, not those of the rich; that they will give and give freely, but they will give from their poverty and the money result will not be large. I said that when our windy and flamboyant President conceived the idea, a year ago, of advertising himself to the world as the new Angel of Peace, and set himself the task of bringing about the peace between Russia and Japan and had the misfortune to accomplish his misbegotten purpose, no one in all this nation except Doctor Seaman and myself uttered a public protest against this folly of follies. That at that time I believed that that fatal peace had postponed the Russian nation's imminent liberation from its age-long chains indefinitely -- probably for centuries; that I believed at that time that Roosevelt had given the Russian revolution its death-blow, and that I am of that opinion yet.

I will mention here, in parenthesis, that I came across Doctor Seaman last night for the first time in my life, and found that his opinion also remains to-day as he expressed it at the time that that infamous peace was consummated.

Tchaykoffsky said that my talk depressed him profoundly, and that he hoped I was wrong.

I said I hoped the same.

He said, "Why, from this very nation of yours came a mighty contribution only two or three months ago, and it made us all glad in Russia. You raised two millions of dollars in a breath -- in a moment, as it were -- and sent that contribution, that most noble and generous contribution, to suffering Russia. Does not that modify your opinion?"

"No," I said, "it doesn't. That money came not from Americans, it came from Jews; much of it from rich Jews, but the most of it from Russian and Polish Jews on the East Side -- that is to say, it came from the very poor. The Jew has always been benevolent. Suffering can always move a Jew's heart and tax his pocket to the limit. He will be at your mass meetings. But if you find any Americans there put them in a glass case and exhibit them. It will be worthy fifty cents a head to go and look at that show and try to believe in it."

He asked me to come to last night's meeting and speak, but I had another engagement and could not do it. Then he asked me to write a line or two which could be read at the meeting, and I did that cheerfully (36).

Twain inserted into his autobiography a clipping of

The New York Times news story for March 30, 1906 containing the text of his letter that he gave Tchaykovsky to read:

DEAR MR. TCHAYKOFFSKY:

I thank you for the honor of the invitation, but I am not able to accept it because Thursday evening I shall be presiding at a meeting whose object is to find remunerative work for certain classes of our blind who would gladly support themselves if they had the opportunity.

My sympathies are with the Russian revolution, of course. It goes without saying. I hope it will succeed, and now that I have talked with you I take heart to believe it will. Government by falsified promises, by lies, by treachery, and by the butcher knife, for the aggrandizement of a single family of drones and its idle and vicious kin has been borne quite long enough in Russia, I should think. And it is to be hoped that the roused nation, now rising in its strength, will presently put an end to it and set up the republic in its place. Some of us, even the white-headed, may live to see the blessed day when czars and grand dukes will be as scarce there as I trust they are in heaven.

Most sincerely yours,

MARK TWAIN (37).

_____

AN INVITATION FROM IVAN NARODNY

Throughout April 1906 the New York newspapers continued to report on the volcanic eruption of Vesuvius as well as incoming Russian revolutionaries. On April 7,

The New York Times published an interview with Ivan Narodny. The

Times described Narodny as a "chief agent" of the Russian revolution; 36 years old; having a half dozen aliases; and the leader of a mutiny among the military in Cronstadt, Russia in October 1905. Narodny told the interviewer how Cossack soldiers had killed his wife and children and burned his home. Narodny was a man with a Czar's bounty on his head. In a lengthy interview Narodny spelled out the disappointments of the Russian people with reforms that had been promised after the Treaty of Portsmouth but never materialized. Narodny emphasized the need for American funds to purchase arms and ammunition for the revolutionary army they were building (

38).

Ivan Narodny from The Saturday Evening Post, April 7, 1906.

Ivan Narodny from The Saturday Evening Post, April 7, 1906.

Also appearing on April 7, 1906 was a lengthy story in

The Saturday Evening Post by Ernest Poole which featured an interview with Narodny titled "Till Russia Shall Be Free." Poole's feature told of Narodny's daring deeds; time spent in prison for revolutionary activities; and a variety of disguises, aliases and escapes that had brought Narodny to America in search of funding for a Russian revolution.

Later reports from files in the Bureau of Investigation indicate Narodny's previous name was Jaan Sibul (translated to English as John Onion) who had served time in prison in Estonia in 1898. He had later changed his name to Jaan Tasaneh and left a wife and children in Verro when he came to America (

39). The facts of Narodny's life and activities have never been firmly established.

Three days after Narodny's interview appeared in

The New York Times and

The Saturday Evening Post, he sent a letter to Mark Twain inviting him to "give us the pleasure of your company at dinner Wednesday evening, April 11th, at seven o'clock, to meet Maxim Gorky" (

40).

_____

MAXIM GORKY ARRIVES IN AMERICA

Mark Twain had dinner with Charlotte Teller the night before Gorky's arrival at 3 Fifth Avenue. Twain's secretary Isabel Lyon recorded in her diary the following morning on April 11:

Last night Mr. Clemens dined with Mrs. Johnson and her revolutionary tribe -- Narodny and others. No -- Narodny wasn't there either -- but he's to be there tonight, and Gorky too. A buck dinner (41).

What was discussed between Teller and Clemens the evening before Gorky's arrival at 3 Fifth Avenue is not known. However, other residents at the "A Club" had become aware of a pending crisis related to the Gorky visit -- Gorky was bringing with him his common law wife Maria Andreyeva, an actress in the Moscow Art Theatre. (Her name was alternately spelled "Andreiva" in some news reports.) Gorky, in poor political standing with both the church and government in Russia, had never obtained a legal divorce from his first wife. Ivan Narodny had been alerted by Russian banker V. Zaharov that the Czar's agents Ambassador Baron Rosen and Colonel Nikolayev had plans to turn American public against Gorky by giving the American newspapers photos of Gorky's legal wife Katharine Pavlovna Volzhina and two children who were left behind in Russia. If Twain learned of Gorky's marital situation prior to meeting him and pledging his support, he never indicated advance knowledge (

42).

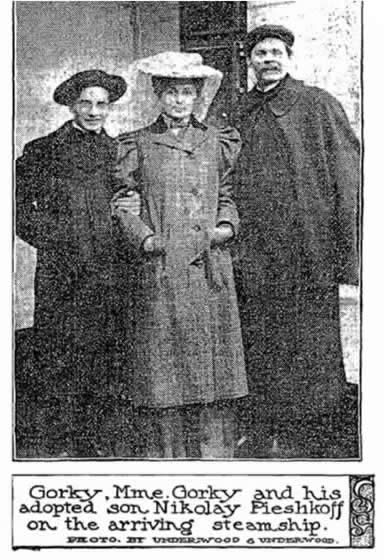

Photo of Gorky upon his arrival in New York

Photo of Gorky upon his arrival in New York

from The New York Times, April 15, 1906, p. SM1.

Gorky arrived in New York on April 10, 1906 and was met aboard the ship by his American host Gaylord Wilshire, editor of

Wilshire's Magazine which was advertised as "the Greatest Socialist Magazine in the World" with a circulation of 300,000; Ivan Narodny; Leroy Scott, author the 1905 novel about labor unions titled

The Walking Delegate; Abraham Cahan, editor of the Jewish-language socialist daily newspaper

Vorwaerts (English translation:

Jewish Daily Forward); and several others. The group attempted to persuade Gorky to allow Maria Andreyeva to stay at the Staten Island, New York home of John and Prestonia Mann Martin while Gorky would lodged at 3 Fifth Avenue. John Martin, a native of England and a naturalized American citizen, was a prominent member of the Fabian Socialist society and a member of the executive committee of the American Friends of Russian Freedom. Gorky refused the suggestion. Gorky and Andreyeva were booked into the Hotel Bellclaire at 77th and Broadway in suites reserved for them by Wilshire.

_____

TWAIN AT THE GORKY DINNER

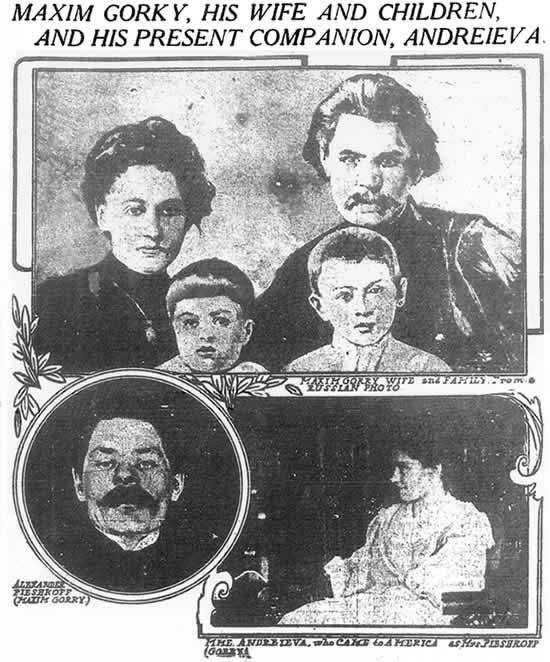

Mark Twain at the "A Club" house at a dinner for Maxim Gorky.

Mark Twain at the "A Club" house at a dinner for Maxim Gorky.

Front row, L-R: Zinovy Peshkov (Gorky's adopted son and translator), Maxim Gorky, Mark Twain, and Ivan Narodny.

On Wednesday, April 11, 1906 Mark Twain attended a dinner at 3 Fifth Avenue in response to Narodny's invitation. Also present were Nikolai Tchaykovsky; Robert Collier; Nikolas Burenin, Gorky's friend and private secretary; Arthur Brisbane; David Graham Phillips; Robert Hunter; Ernest Poole; Dr. Walter Weyl; Leroy M. Scott; and Howard Brubaker. Zinovy Peshkoff, Gorky's adopted son who was employed in the offices of Gaylord Wilshire, acted as translator for Gorky who was unable to speak, read or write English (

43). William Dean Howells and Peter Finley Dunne had been invited but did not attend.

Gorky was extremely delighted to meet Mark Twain. He had earlier told reporters that Mark Twain was well regarded in Russia:

In Russia Mark Twain is almost a cart of everybody's education. There are hundreds of editions of his works in my country (44).

The New York Times, in their story dated April 12, 1906 headlined

"Gorky and Twain Plead for Revolution" ran the text of Twain's speech that evening:

"If we can build a Russian republic to give to the persecuted people of the Czar's domain the same measure of freedom that we enjoy, let us go ahead and do it," said Mark Twain. "We need not discuss the method by which that purpose is to be attained. Let us hope that fighting will be postponed or averted for a while, but if it must come -- " Mr. Clemens's hiatus was significant.

"I am most emphatically in sympathy with the movement now on foot in Russia to make that country free," he went on. "I am certain that it will be successful, as it deserves to be. Anybody whose ancestors were in this country when we were trying to free ourselves from oppression must sympathize with those who now are trying to do the same thing in Russia.