Via a Facebook friend

[JB Note: The below may be helpful to the fewer and fewer Americans studying Russian, if they not wish to be discouraged by the tricky Russian verb -- including on how to distinguish its "perfective" and "imperfective" tenses. In U.S. high schools/colleges the teaching of "English" (are there still courses under that designation, given the dismissal of grammar by U.S. educational authorities?) does not underscore the subtle verbal temporal distinctions, mentioned below, existing (up to now) in American English, but that are (still) prevalent in Russian. Hence (allow me to speculate, as a total non-linguist/grammarian) that Americans who wish to learn/understand Russia through her wonderfully complex language might find helpful the below (written by a great American writer, on the distinctions between the "perfect" and "imperfect "-- I'm referring to the tenses, if "ive" is added :) -- in English), relevant to distinguishing between the sovershenyi (perfective) and nesovershenyi (imperfective) tenses.

P.S. Russian verbs of motion are an infinitely more difficult grammatical, if not cultural, task for "Let's Go Now, No Matter How" Americans. But I'll leave such deep explanations to the experts.

From: English Language, Food and Drink| June 25th, 2015

P.S. Russian verbs of motion are an infinitely more difficult grammatical, if not cultural, task for "Let's Go Now, No Matter How" Americans. But I'll leave such deep explanations to the experts.

From: English Language, Food and Drink| June 25th, 2015

I regularly meet up with speaking partners who help me learn their languages in exchange for my helping them learn English. Even though they usually speak much better English already than I speak Korean, Spanish, Japanese, or what have you, I often feel like I’ve got the heavier end of the job. Why? Because the English language, for all its advantages — its global reach, the ease with which it incorporates foreign terms and neologisms, its wealth of descriptive possibility — has the major disadvantage of seldom making immediate sense.

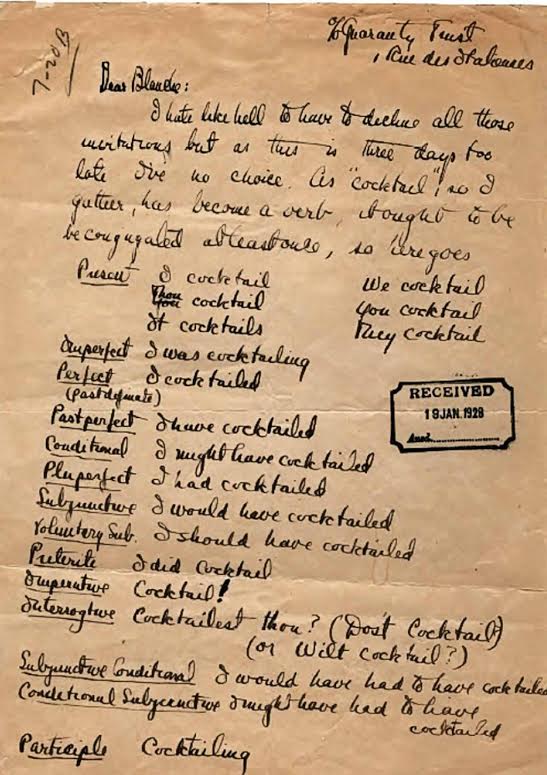

From English’s great flexibility flows great frustration: how many times have foreign friends put up a piece of text to me — often from respected, canonical works of English literature — and demanded an explanation? They’ve usually stumbled over some obscure usage that qualifies as at least unorthodox and perhaps downright ungrammatical, but nonetheless intuitively understandable — if only to a native speaker like me. Here we have one example of just such a linguistic invention refined by no less a respected, canonical writer than F. Scott Fitzgerald: the verb “to cocktail.”

“As ‘cocktail,’ so I gather, has become a verb, it ought to be conjugated at least once,” wrote the author of The Great Gatsby in a 1928 letter to Blanche Knopf, the wife of publisher Alfred A. Knopf. Who better to first lay out its full conjugation than the man who, as the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center puts it, “gave the Jazz Age its name”? Given that his fame “was for many years based less on his work than his personality—the society playboy, the speakeasy alcoholic whose career had ended in ‘crack-up,’ the brilliant young writer whose early literary success seemed to make his life something of a romantic idyll,” he found himself well placed to offer the language a new “taste of Roaring Twenties excess.”

And so Fitzgerald breaks it down:

Present: I cocktail, thou cocktail, we cocktail, you cocktail, they cocktail.

Imperfect: I was cocktailing.

Perfect or past definite: I cocktailed.

Past perfect: I have cocktailed.

Conditional: I might have cocktailed.

Pluperfect: I had cocktailed.

Subjunctive: I would have cocktailed.

Voluntary subjunctive: I should have cocktailed.

Preterit: I did cocktail.

No comments:

Post a Comment