Excerpt from: Elizabeth Drew, "Terrifying Trump," New York Review of Books; see also, plus (1).

image from article

Trump’s possible mental deficiencies are also a troubling question: serious medical professionals suspect he has narcissistic personality disorder [JB - see], and also oncoming dementia [JB - see] , judging from his limited vocabulary. (If one compares his earlier appearances on YouTube, for example a 1988 interview with Larry King [JB - see], it appears that Trump used to speak more fluently and coherently than he does now, especially in some of his recent rambling presentations.) His perseverating about such matters as the size of his inauguration crowd, or the fantasy that three to five million illegal voters denied him a popular vote victory (he got these estimates from a dodgy source who has yet to offer documentation), or, as he told CIA employees, the number of times he’s been on the cover of Time (sometimes inflating the actual number) has become a joke, but it also suggests that there may be something troubling about his mental state. Numerous eminent psychologists and psychiatrists have written about or expressed their concerns about Trump’s mental stability.2(2) They did this despite the fact that the American Psychiatric Association has a rule that a diagnosis shouldn’t be proffered unless the person under discussion has been clinically examined.

***

Image from, with caption: Dr. Harold Bornstein wrote “I am pleased to report that Mr. Trump has had no significant medical problems."

Bornstein specializes in internal medicine and gastroenterology and is affiliated with Lenox Hill Hospital on the Upper East Side, according to his website.

from; NOTE MENTION OF STATIN IN THE ABOVE LETTER

***

Statin

Statin

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the group of cholesterol-lowering drugs. For the amino acid, see Statine. For inhibiting hormones, see Releasing and inhibiting hormones.

| Statin | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

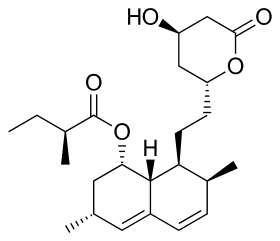

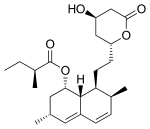

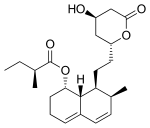

Lovastatin, a compound isolated from Aspergillus terreus, was the first statin to be marketed.

| |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | High cholesterol |

| ATC code | C10AA |

| Biological target | HMG-CoA reductase |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | Drug Classes |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D019161 |

| In Wikidata | |

Statins, also known as HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, are a class of lipid-lowering medications. Statins have been found to reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality in those who are at high risk. The evidence is strong that statins are effective for treating CVD in the early stages of a disease (secondary prevention) and in those at elevated risk but without CVD (primary prevention).[1][2]

Side effects of statins include muscle pain, increased risk of diabetes mellitus, and abnormalities in liver enzyme tests.[3] Additionally, they have rare but severe adverse effects, particularly muscle damage.[4] They inhibit the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase which plays a central role in the production of cholesterol. High cholesterol levels have been associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD).[5]

As of 2010, a number of statins are on the market: atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin and simvastatin.[6] Several combination preparations of a statin and another agent, such as ezetimibe/simvastatin, are also available. In 2005, sales were estimated at US$18.7 billion in the United States.[7] The best-selling statin is atorvastatin, which in 2003 became the best-selling pharmaceutical in history.[8] The manufacturer Pfizer reported sales of US$12.4 billion in 2008.[9] Due to patent expirations, several statins are now[when?] available as less expensive generics.[10][11]

Contents

[hide]Medical uses[edit]

Clinical practice guidelines generally recommend people to try "lifestyle modification", including a cholesterol-lowering diet and physical exercise, before statin use. Statins or other pharmacologic agents may be recommended for those who do not meet their lipid-lowering goals through diet and lifestyle changes.[12][13] Statins appear to work equally well in males and females.[14]

Primary prevention[edit]

In 2016 the United States Preventative Services Task Force recommended statins for those who have at least one risk factor for heart disease, are between 40 and 75 years old, and have at least a 10% risk of heart disease.[15] The risk factors for heart disease included dyslipidemia, diabetes, high blood pressure, and smoking.[15] The risk of heart disease is estimated using the ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort equation.[16] They recommended selective use of low-to-moderate doses statins in the same adults who have a calculated 10-year CVD event risk of 7.5–10% or greater.[15]

Most evidence suggests that statins are effective in preventing heart disease in those with high cholesterol, but no history of heart disease. A 2013 Cochrane review found a decrease in risk of death and other poor outcomes without any evidence of harm.[2] For every 138 people treated for 5 years one fewer dies and for every 49 treated one fewer has an episode of heart disease.[7] A 2011 review reached similar conclusions.[17] And a 2012 review found benefits in both women and men.[18] A 2010 review concluded that treating people with no history of cardiovascular disease reduces cardiovascular events in men but not women, and provides no mortality benefit in either sex.[19] Two other meta analyses published that year, one of which used data obtained exclusively from women, found no mortality benefit in primary prevention.[20][21]

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends statin treatment for adults with an estimated 10 year risk of developing cardiovascular disease that is greater than 10%.[22] Guidelines by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association recommend statin treatment for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with LDL cholesterol ≥ 190 mg/dL or those with diabetes, age 40–75 with LDL-C 70–190 mg/dl; or in those with a 10-year risk of developing heart attack or stroke of 7.5% or more. In this latter group, statin assignment was not automatic, but was recommended to occur only after a clinician-patient risk discussion with shared decision making where other risk factors and lifestyle are addressed, the potential for benefit from a statin is weighed against the potential for adverse effects or drug interactions and informed patient preference is elicited. Moreover, if a risk decision was uncertain, factors such as family history, coronary calcium score, ankle-brachial index, and an inflammation test (hs-CRP ≥ 2.0 mg/L) were suggested to inform the risk decision. Additional factors that could be used were an LDL-C ≥ 160 or a very high lifetime risk.[23] However, critics such as Steven E. Nissen say that the AHA/ACC guidelines were not properly validated, overestimate the risk by at least 50%, and recommend statins for patients who will not benefit, based on populations whose observed risk is lower than predicted by the guidelines.[24] The European Society of Cardiology and the European Atherosclerosis Society recommend the use of statins for primary prevention, depending on baseline estimated cardiovascular score and LDL thresholds.[25]

Secondary prevention[edit]

Statins are effective in decreasing mortality in people with pre-existing CVD. They are also advocated for use in patients at high risk of developing heart disease.[26] On average, statins can lower LDL cholesterol by 1.8 mmol/l (70 mg/dl), which translates into an estimated 60% decrease in the number of cardiac events (heart attack, sudden cardiac death) and a 17% reduced risk of stroke after long-term treatment.[27] They have less effect than the fibrates or niacin in reducing triglycerides and raising HDL-cholesterol ("good cholesterol").

Statins have been studied for improving operative outcomes in cardiac and vascular surgery.[28] Mortality and adverse cardiovascular events were reduced in statin groups.[29]

Comparative effectiveness[edit]

While no direct comparison exists, all statins appear effective regardless of potency or degree of cholesterol reduction.[30] There do appear to be some differences between them, with simvastatin and pravastatin appearing superior in terms of side-effects.[3]

A comparison of atorvastatin, pravastatin and simvastatin, based on their effectiveness against placebos, found, at commonly prescribed doses, no differences among the statins in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and lipids.[31]

Children[edit]

In children statins are effective at reducing cholesterol levels in those with familial hypercholesterolemia.[32][needs update] Their long term safety is, however, unclear.[32][33] Some recommend that if lifestyle changes are not enough statins should be started at 8 years old.[34]

Familial hypercholesterolemia[edit]

Statins may be less effective in reducing LDL cholesterol in people with familial hypercholesterolemia, especially those with homozygous deficiencies.[35] These people have defects usually in either the LDL receptor or apolipoprotein B genes, both of which are responsible for LDL clearance from the blood.[36] Statins are still first line treatments in familial hypercholesterolemia,[35]although other cholesterol-reducing measures may be required.[37] In people with homozygous deficiencies, statins may still prove helpful, albeit at high doses and in combination with other cholesterol-reducing medications.[38]

Contrast induced nephropathy[edit]

A 2014 meta-analysis found that statins could reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy by 53% in people undergoing coronary angiography/percutaneous interventions. The effect was found to be stronger among those with preexisting kidney dysfunction or diabetes mellitus.[39]

Adverse effects[edit]

| Choosing a statin for people with special considerations[40] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Commonly recommended statins | explanation | |

| Kidney transplantation recipients taking ciclosporin | Pravastatin or Fluvastatin | Drug interactions are possible, but studies have not shown that these statins increase exposure to ciclosporin.[41] | |

| HIV-positive people taking protease inhibitors | Atorvastatin, Pravastatin or Fluvastatin | Negative interactions are more likely with other choices[42] | |

| Persons taking gemfibrozil, a non-statin cholesterol-lowering drug | Atorvastatin | Combining gemfibrozil and a statin increases risk of rhabdomyolysis and subsequently kidney failure[43][44] | |

| Persons taking the anticoagulant warfarin | Any statin | The statin use may require that the warfarin dose be changed, as some statins increase the effect of warfarin.[45] | |

The most important adverse side effects are muscle problems, an increased risk of diabetes, and increased liver enzymes in the blood due to liver damage.[46][47] Over 5 years of treatment statins result in 75 cases of diabetes, 7.5 cases of bleeding stroke, and 5 cases of muscle damage per 10,000 people treated.[48] This could be because as statins inhibit the enzyme (HMG-CoA reductase) that makes cholesterol, statins also inhibit the other processes of this enzyme, such as CoQ10production, and CoQ10production is important for muscle cells and in blood sugar regulation.[49]

Other possible adverse effects include cognitive loss, neuropathy, pancreatic and hepatic dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction.[50] The rate at which such events occur has been widely debated, in part because the risk/benefit ratio of statins in low risk populations is highly dependent on the rate of adverse events.[51][52][53] A Cochrane group meta analysis of statin clinical trials in primary prevention found no evidence of excess adverse events among those treated with statins compared to placebo.[54] Another meta analysis found a 39% increase in adverse events in statin treated people relative to those receiving placebo, but no increase in serious adverse events.[55] The author of one study argued that adverse events are more common in clinical practice than in randomized clinical trials.[50] A systematic review concluded that while clinical trial meta analyses underestimate the rate of muscle pain associated with statin use, the rates of rhabdomyolysis are still "reassuringly low" and similar to those seen in clinical trials (about 1–2 per 10,000 person years).[56] A systematic review co-authored by Ben Goldacre concluded that only a small fraction of side effects reported by people on statins are actually attributable to the statin.[57]

Cognitive effects[edit]

There are anecdotal reports of cognitive decline with statins.[58] In 2012, in recognition of an increase in anecdotal reports and increasing concerns over the relationship between statins and memory loss (including reports of transient global amnesia), forgetfulness and confusion, the Food and Drug Administration(FDA) added to its required labeling on statin drugs a warning about possible cognitive impacts.[59] The effects are described as rare, non-serious, and reversible upon cessation of treatment.[60]

One 2013 systematic review concluded that the available evidence was "not strongly supportive of a major adverse effect of statins".[61] Another meta-analysis from the same year concluded that there is moderate quality evidence of no increase in dementia, mild cognitive impairment or cognitive performance scores, although the strength of the evidence was limited, particularly for high doses.[62]

Muscles[edit]

In observational studies 10–15% of people who take statins experience muscle problems; in most cases these consist of muscle pain.[4] These rates, which are much higher than those seen in randomized clinical trials[56] have been the topic of extensive[citation needed] debate and discussion.

Rare reactions include myopathies such as myositis (inflammation of the muscles) or even rhabdomyolysis (destruction of muscle cells), which can in turn result in life-threatening kidney injury. The risk of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis increases with older age, use of interacting medications such as fibrates, and hypothyroidism.[63] Coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone) levels are decreased in statin use;[64] CoQ10 supplements are sometimes used to treat statin-associated myopathy, though evidence of their efficacy is lacking as of 2007.[65] The gene SLCO1B1 (Solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1) codes for an organic anion-transporting polypeptide that is involved in the regulation of the absorption of statins. A common variation in this gene was found in 2008 to significantly increase the risk of myopathy.[66]

Records exist of over 250,000 people treated from 1998 to 2001 with the statin drugs atorvastatin, cerivastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin.[67] The incidence of rhabdomyolyis was 0.44 per 10,000 patients treated with statins other than cerivastatin. However, the risk was over 10-fold greater if cerivastatin was used, or if the standard statins (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, or simvastatin) were combined with fibrate (fenofibrate or gemfibrozil) treatment. Cerivastatin was withdrawn by its manufacturer in 2001.[citation needed]

All commonly used statins show somewhat similar results, but the newer statins, characterized by longer pharmacological half-lives and more cellular specificity, have had a better ratio of efficacy to lower adverse effect rates.[citation needed] Some researchers have suggested hydrophilic statins, such as fluvastatin, rosuvastatin, and pravastatin, are less toxic than lipophilic statins, such as atorvastatin, lovastatin, and simvastatin, but other studies have not found a connection;[68] the risk of myopathy was suggested to be lowest with pravastatin and fluvastatin, probably because they are more hydrophilic and as a result have less muscle penetration.[citation needed] Lovastatin induces the expression of gene atrogin-1, which is believed to be responsible in promoting muscle fiber damage.[68] Tendon rupture does not appear to occur.[69]

Diabetes[edit]

Statins are associated with a slightly increased risk of diabetes (2–17% in one review).[70] Higher doses have a greater effect, but the decrease in cardiovascular disease outweighs the risk of developing diabetes.[71]

Cancer[edit]

Several meta-analyses have found no increased risk of cancer, and some meta-analyses have found a reduced risk.[72][73][74][75][76]

Statins may reduce the risk of esophageal cancer,[77] colorectal cancer,[78] gastric cancer,[79][80] hepatocellular carcinoma,[81] and possibly prostate cancer.[82][83] They appear to have no effect on the risk of lung cancer,[84] kidney cancer,[85] breast cancer,[86]pancreatic cancer,[87] or bladder cancer.[88]

Drug interactions[edit]

Combining any statin with a fibrate or niacin (other categories of lipid-lowering drugs) increases the risks for rhabdomyolysis to almost 6.0 per 10,000 person-years.[67] Monitoring liver enzymes and creatine kinase is especially prudent in those on high-dose statins or in those on statin/fibrate combinations, and mandatory in the case of muscle cramps or of deterioration in kidney function.

Consumption of grapefruit or grapefruit juice inhibits the metabolism of certain statins. Bitter oranges may have a similar effect.[89]Furanocoumarins in grapefruit juice (i.e. bergamottin and dihydroxybergamottin) inhibit the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A4, which is involved in the metabolism of most statins (however, it is a major inhibitor of only lovastatin, simvastatin, and to a lesser degree, atorvastatin) and some other medications[90] (flavonoids (i.e. naringin) were thought to be responsible). This increases the levels of the statin, increasing the risk of dose-related adverse effects (including myopathy/rhabdomyolysis). The absolute prohibition of grapefruit juice consumption for users of some statins is controversial.[91]

The FDA notified healthcare professionals of updates to the prescribing information concerning interactions between protease inhibitors and certain statin drugs. Protease inhibitors and statins taken together may increase the blood levels of statins and increase the risk for muscle injury (myopathy). The most serious form of myopathy, rhabdomyolysis, can damage the kidneys and lead to kidney failure, which can be fatal.[92]

Mechanism of action[edit]

Main article: Cholesterol homeostasis

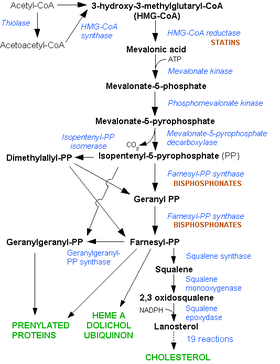

Statins act by competitively inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, the first committed enzyme of the mevalonate pathway. Because statins are similar in structure to HMG-CoA on a molecular level, they will fit into the enzyme's active site and compete with the native substrate (HMG-CoA). This competition reduces the rate by which HMG-CoA reductase is able to produce mevalonate, the next molecule in the cascade that eventually produces cholesterol. A variety of natural statins are produced by Penicillium and Aspergillus fungi as secondary metabolites. These natural statins probably function to inhibit HMG-CoA reductase enzymes in bacteria and fungi that compete with the producer.[94]

Inhibiting cholesterol synthesis[edit]

By inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, statins block the pathway for synthesizing cholesterol in the liver. This is significant because most circulating cholesterol comes from internal manufacture rather than the diet. When the liver can no longer produce cholesterol, levels of cholesterol in the blood will fall. Cholesterol synthesis appears to occur mostly at night,[95] so statins with short half-lives are usually taken at night to maximize their effect. Studies have shown greater LDL and total cholesterol reductions in the short-acting simvastatin taken at night rather than the morning,[96][97] but have shown no difference in the long-acting atorvastatin.[98]

Increasing LDL uptake[edit]

In rabbits, liver cells sense the reduced levels of liver cholesterol and seek to compensate by synthesizing LDL receptors to draw cholesterol out of the circulation.[99] This is accomplished via proteases that cleave membrane-bound sterol regulatory element binding proteins, which then migrate to the nucleus and bind to the sterol response elements. The sterol response elements then facilitate increased transcription of various other proteins, most notably, LDL receptor. The LDL receptor is transported to the liver cell membrane and binds to passing LDL and VLDL particles (colloquially, "bad cholesterol"), mediating their uptake into the liver, where the cholesterol is reprocessed into bile salts and other byproducts. The bile salts are secreted into the duodenum during digestion of fats and are subsequently reabsorbed later in the jejunum and ileum.[citation needed]

Decreasing of specific protein prenylation[edit]

Statins, by inhibiting the HMG CoA reductase pathway, simultaneously inhibit the production of both cholesterol and specific prenylated proteins (see diagram).This inhibitory effect on protein prenylation may be involved, at least partially, in the improvement of endothelial function, modulation of immune function, and other pleiotropic cardiovascular benefits of statins,[100][101][102][103][104][105] as well as in the fact that a number of other drugs that lower LDL have not shown the same cardiovascular risk benefits in studies as statins,[106] and may also account for certain of the benefits seen in cancer reduction with statins.[107] In addition, the inhibitory effect on protein prenylation may also be involved in a number of unwanted side effects associated with statins, including muscle pain (myopathy)[108] and elevated blood sugar (diabetes).[109]

Other effects[edit]

As noted above, statins exhibit action beyond lipid-lowering activity in the prevention of atherosclerosis. The ASTEROID trial showed direct ultrasound evidence of atheroma regression during statin therapy.[110] Researchers hypothesize that statins prevent cardiovascular disease via four proposed mechanisms (all subjects of a large body of biomedical research):[111]

- Improve endothelial function

- Modulate inflammatory responses

- Maintain plaque stability

- Prevent thrombus formation

In 2008, the JUPITER study showed benefit in those who had no history of high cholesterol or heart disease, but only elevated C-reactive protein levels.[112] The conclusions of this study are, however, controversial.[113][114][115]

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

Available forms[edit]

The statins are divided into two groups: fermentation-derived and synthetic. They include, along with brand names, which may vary between countries:

| Statin | Image | Brand name | Derivation | Metabolism[116] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

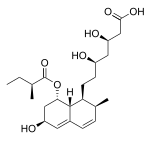

| Atorvastatin | Lipitor, Ator | Synthetic | CYP3A4 | |

| Cerivastatin | Lipobay, Baycol (withdrawn from the market in August, 2001 due to risk of serious rhabdomyolysis) | Synthetic | various CYP3A isoforms[117] | |

| Fluvastatin | Lescol, Lescol XL | Synthetic | CYP2C9 | |

| Lovastatin | Mevacor, Altocor, Altoprev | Naturally occurring, fermentation-derived compound. It is found in oyster mushrooms and red yeast rice | CYP3A4 | |

| Mevastatin | Compactin | Naturally occurring compound found in red yeast rice | CYP3A4 | |

| Pitavastatin | Livalo, Livazo, Pitava | Synthetic | CYP2C9 and CYP2C8 (minimally) | |

| Pravastatin | Pravachol, Selektine, Lipostat | Fermentation-derived (a fermentation product of bacterium Nocardia autotrophica) | Non-CYP[118] | |

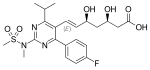

| Rosuvastatin | Crestor | Synthetic | CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 | |

| Simvastatin | Zocor, Lipex | Fermentation-derived (simvastatin is a synthetic derivate of a fermentation product of Aspergillus terreus) | CYP3A4 | |

| Simvastatin + ezetimibe | Vytorin, Inegy | Combination therapy: statin + cholesterol absorption inhibitor | ||

| Lovastatin + niacin extended-release | Advicor, Mevacor | Combination therapy | ||

| Atorvastatin + amlodipine | Caduet, Envacar | Combination therapy: statin + calcium antagonist | ||

| Simvastatin + niacin extended-release | Simcor | Combination therapy |

LDL-lowering potency varies between agents. Cerivastatin is the most potent, (withdrawn from the market in August, 2001 due to risk of serious rhabdomyolysis) followed by (in order of decreasing potency), rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and fluvastatin.[119] The relative potency of pitavastatin has not yet been fully established.[citation needed]

Some types of statins are naturally occurring, and can be found in such foods as oyster mushrooms and red yeast rice. Randomized controlled trials have found these foodstuffs to reduce circulating cholesterol, but the quality of the trials has been judged to be low.[120] Due to patent expiration, most of the block-buster branded statins have been generic since 2012, including atorvastatin, the largest-selling branded drug.[citation needed]

| Statin equivalent dosages | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % LDL reduction (approx.) | Atorvastatin | Fluvastatin | Lovastatin | Pravastatin | Rosuvastatin | Simvastatin |

| 10–20% | – | 20 mg | 10 mg | 10 mg | – | 5 mg |

| 20–30% | – | 40 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg | – | 10 mg |

| 30–40% | 10 mg | 80 mg | 40 mg | 40 mg | 5 mg | 20 mg |

| 40–45% | 20 mg | – | 80 mg | 80 mg | 5–10 mg | 40 mg |

| 46–50% | 40 mg | – | – | – | 10–20 mg | 80 mg* |

| 50–55% | 80 mg | – | – | – | 20 mg | – |

| 56–60% | – | – | – | – | 40 mg | – |

| * 80-mg dose no longer recommended due to increased risk of rhabdomyolysis | ||||||

| Starting dose | ||||||

| Starting dose | 10–20 mg | 20 mg | 10–20 mg | 40 mg | 10 mg; 5 mg if hypothyroid, >65 yo, Asian | 20 mg |

| If higher LDL reduction goal | 40 mg if >45% | 40 mg if >25% | 20 mg if >20% | -- | 20 mg if LDL >190 mg/dL (4.87 mmol/L) | 40 mg if >45% |

| Optimal timing | Anytime | Evening | With evening meals | Anytime | Anytime | Evening |

History[edit]

Main article: Statin development

In 1971, Akira Endo, a Japanese biochemist working for the pharmaceutical company Sankyo, began the search for a cholesterol-lowering drug. Research had already shown cholesterol is mostly manufactured by the body in the liver, using the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase.[8] Endo and his team reasoned that certain microorganisms may produce inhibitors of the enzyme to defend themselves against other organisms, as mevalonate is a precursor of many substances required by organisms for the maintenance of their cell walls (ergosterol) or cytoskeleton (isoprenoids).[94] The first agent they identified was mevastatin (ML-236B), a molecule produced by the fungus Penicillium citrinum.

A British group isolated the same compound from Penicillium brevicompactum, named it compactin, and published their report in 1976.[121] The British group mentions antifungal properties, with no mention of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition.[citation needed]

Mevastatin was never marketed, because of its adverse effects of tumors, muscle deterioration, and sometimes death in laboratory dogs. P. Roy Vagelos, chief scientist and later CEO of Merck & Co, was interested, and made several trips to Japan starting in 1975. By 1978, Merck had isolated lovastatin (mevinolin, MK803) from the fungus Aspergillus terreus, first marketed in 1987 as Mevacor.[8]

A link between cholesterol and cardiovascular disease, known as the lipid hypothesis, had already been suggested. Cholesterol is the main constituent of atheroma, the fatty lumps in the wall of arteries that occur in atherosclerosis and, when ruptured, cause the vast majority of heart attacks. Treatment consisted mainly of dietary measures, such as a low-fat diet, and poorly tolerated medicines, such as clofibrate, cholestyramine, and nicotinic acid. Cholesterol researcher Daniel Steinberg writes that while the Coronary Primary Prevention Trial of 1984 demonstrated cholesterol lowering could significantly reduce the risk of heart attacks and angina, physicians, including cardiologists, remained largely unconvinced.[122]

Society and culture[edit]

To market statins effectively, Merck had to convince the public of the dangers of high cholesterol, and doctors that statins were safe and would extend lives. As a result of public campaigns, people in the United States became familiar with their cholesterol numbers and the difference between "good" and "bad" cholesterol, and rival pharmaceutical companies began producing their own statins, such as pravastatin (Pravachol), manufactured by Sankyo and Bristol-Myers Squibb. In April 1994, the results of a Merck-sponsored study, the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study, were announced. Researchers tested simvastatin, later sold by Merck as Zocor, on 4,444 patients with high cholesterol and heart disease. After five years, the study concluded the patients saw a 35% reduction in their cholesterol, and their chances of dying of a heart attack were reduced by 42%.[8][123] In 1995, Zocor and Mevacor both made Merck over US$1 billion.[8] Endo was awarded the 2006 Japan Prize, and the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award in 2008. For his "pioneering research into a new class of molecules" for "lowering cholesterol,"[124] Endo was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Alexandria, Virginia in 2012. Michael C. Brown and Joseph Goldstein, who won the Nobel Prize for related work on cholesterol, said of Endo: "The millions of people whose lives will be extended through statin therapy owe it all to Akira Endo."[125]

Research[edit]

Research continues into other areas where specific statins also appear to have a favorable effect, including dementia,[126] lung cancer,[127] nuclear cataracts,[128] hypertension,[129][130] and prostate cancer.[131]

References[edit]

- ^ "Lipid Modification: Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and the Modification of Blood Lipids for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease." (PDF). National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). July 2014. PMID 25340243.

- ^ a b Taylor F; Huffman MD; Macedo AF; Moore TH; Burke M; Davey Smith G; Ward K; Ebrahim S (2013). "Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1: CD004816. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5. PMID 23440795.

- ^ a b Naci H, Brugts J, Ades T (2013). "Comparative tolerability and harms of individual statins: a study-level network meta-analysis of 246 955 participants from 135 randomized, controlled trials". Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 6 (4): 390–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000071. PMID 23838105.

- ^ a b Abd TT, Jacobson TA (May 2011). "Statin-induced myopathy: a review and update.". Expert opinion on drug safety. 10 (3): 373–87. doi:10.1517/14740338.2011.540568. PMID 21342078.

- ^ Lewington S; Whitlock G; Clarke R; Sherliker P; Emberson J; Halsey J; Qizilbash N; Peto R; Collins R (December 2007). "Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths". Lancet. 370 (9602): 1829–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. PMID 18061058.

- ^ Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Cardiovascular drugs". Martindale: the complete drug reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 1155–434. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ a b Taylor, FC; Huffman, M; Ebrahim, S (11 December 2013). "Statin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.". JAMA. 310 (22): 2451–2. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281348. PMID 24276813.

- ^ a b c d e Simons, John (2003-01-20). "The $10 Billion Pill". Fortune."The $10 Billion Pill". PMID 12602122.

- ^ "Doing Things Differently", Pfizer 2008 Annual Review, April 23, 2009, p. 15.

- ^ "www.accessdata.fda.gov".

- ^ "www.accessdata.fda.gov".

- ^ National Cholesterol Education Program (2001). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Executive Summary. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. p. 40. NIH Publication No. 01-3670.

- ^ National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (2010). NICE clinical guideline 67: Lipid modification (PDF). London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. p. 38.[dead link]

- ^ Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT), Collaboration; Fulcher, J; O'Connell, R; Voysey, M; Emberson, J; Blackwell, L; Mihaylova, B; Simes, J; Collins, R; Kirby, A; Colhoun, H; Braunwald, E; La Rosa, J; Pedersen, TR; Tonkin, A; Davis, B; Sleight, P; Franzosi, MG; Baigent, C; Keech, A (11 April 2015). "Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials.". Lancet (London, England). 385 (9976): 1397–405. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61368-4. PMID 25579834.

- ^ a b c US Preventive Services Task, Force.; Bibbins-Domingo, K; Grossman, DC; Curry, SJ; Davidson, KW; Epling JW, Jr; García, FA; Gillman, MW; Kemper, AR; Krist, AH; Kurth, AE; Landefeld, CS; LeFevre, ML; Mangione, CM; Phillips, WR; Owens, DK; Phipps, MG; Pignone, MP (15 November 2016). "Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement.". JAMA. 316 (19): 1997–2007. PMID 27838723.

- ^ ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator

- ^ Tonelli M, Lloyd A, Clement F, Conly J, Husereau D, Hemmelgarn B, Klarenbach S, McAlister FA, Wiebe N, Manns B (2011). "Efficacy of statins for primary prevention in people at low cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis". CMAJ. 183 (16): E1189–202. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101280. PMC 3216447

. PMID 21989464.

. PMID 21989464. - ^ Kostis WJ, Cheng JQ, Dobrzynski JM, Cabrera J, Kostis JB (2012). "Meta-analysis of statin effects in women versus men". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 59 (6): 572–82. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.067. PMID 22300691.

- ^ Petretta M, Costanzo P, Perrone-Filardi P, Chiariello M (2010). "Impact of gender in primary prevention of coronary heart disease with statin therapy: a meta-analysis". Int. J. Cardiol. 138 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.08.001. PMID 18793814.

- ^ Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Erqou S, Sever P, Jukema JW, Ford I, Sattar N (2010). "Statins and all-cause mortality in high-risk primary prevention: a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials involving 65,229 participants". Arch. Intern. Med. 170 (12): 1024–31. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.182. PMID 20585067.

- ^ Bukkapatnam RN, Gabler NB, Lewis WR (2010). "Statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular mortality in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Prev Cardiol. 13 (2): 84–90. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7141.2009.00059.x. PMID 20377811.

- ^ "www.nice.org.uk".

- ^ Stone, NJ; Robinson, J; Lichtenstein, AH; Merz, CN; Blum, CB; Eckel, RH; Goldberg, AC; Gordon, D; Levy, D; Lloyd-Jones, DM; McBride, P; Schwartz, JS; Shero, ST; Smith SC, Jr; Watson, K; Wilson, PW (Nov 12, 2013). "2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.". Circulation. 129 (25 Suppl 2): S1–S45. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. PMID 24222016.

- ^ Steven E. Nissen (2014-12-01). "Prevention Guidelines: Bad Process, Bad Outcome". JAMA Intern Med. 174: 1972–1973. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3278.

- ^ Grupo de Trabajo de la Sociedad Europea de Cardiología (ESC) y de la Sociedad Europea de Aterosclerosis, (EAS); Reiner, Z; Catapano, AL; De Backer, G; Graham, I; Taskinen, MR; Wiklund, O; Agewall, S; Alegría, E; John Chapman, M; Durrington, P; Erdine, S; Halcox, J; Hobbs, R; Kjekshus, J; Perrone Filardi, P; Riccardi, G; Storey, RF; Wood, D (Dec 2011). "ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias." (PDF). Revista espanola de cardiologia (English ed.). 64 (12): 1168. doi:10.1016/j.rec.2011.09.015. PMID 24776417.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (March 2010) [May 2008]. "Lipid modification – Cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease – Quick reference guide" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-25.[dead link]

- ^ Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka AR (June 2003). "Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 326 (7404): 1423. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423. PMC 162260

. PMID 12829554.

. PMID 12829554. - ^ de Waal BA, Buise MP, van Zundert AA (January 2015). "Perioperative statin therapy in patients at high risk for cardiovascular morbidity undergoing surgery: a review". Br J Anaesth. 114 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu295. PMID 25186819.

- ^ Antoniou GA, Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Vallabhaneni SR, Brennan JA, Torella F (December 2014). "Meta-analysis of the effects of statins on perioperative outcomes in vascular and endovascular surgery". J Vasc Surg. 61 (2): 519–532. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2014.10.021. PMID 25498191.

- ^ Tonelli M, Lloyd A, Clement F, Conly J, Husereau D, Hemmelgarn B, Klarenbach S, McAlister FA, Wiebe N, Manns B (Nov 8, 2011). "Efficacy of statins for primary prevention in people at low cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association. 183 (16): E1189–E1202. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101280. PMC 3216447

. PMID 21989464.

. PMID 21989464. - ^ Zhou Z, Rahme E, Pilote L (2006). "Are statins created equal? Evidence from randomized trials of pravastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin for cardiovascular disease prevention". Am. Heart J. 151 (2): 273–81. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.04.003. PMID 16442888.

- ^ a b Vuorio, A; Kuoppala, J; Kovanen, PT; Humphries, SE; Strandberg, T; Tonstad, S; Gylling, H (Jul 7, 2010). "Statins for children with familial hypercholesterolemia.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (7): CD006401. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006401.pub2. PMID 20614444.

- ^ Lamaida, N; Capuano, E; Pinto, L; Capuano, E; Capuano, R; Capuano, V (Sep 2013). "The safety of statins in children.". Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 102 (9): 857–62. doi:10.1111/apa.12280. PMID 23631461.

- ^ Braamskamp, MJ; Wijburg, FA; Wiegman, A (Apr 16, 2012). "Drug therapy of hypercholesterolaemia in children and adolescents.". Drugs. 72 (6): 759–72. doi:10.2165/11632810-000000000-00000. PMID 22512364.

- ^ a b Repas TB, Tanner JR (February 2014). "Preventing early cardiovascular death in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia". J Am Osteopath Assoc. 114 (2): 99–108. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2014.023. PMID 24481802.[dead link]

- ^ Ramasamy, I. (2015-11-04). "Update on the molecular biology of dyslipidemias". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 454: 143–185. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2015.10.033. ISSN 1873-3492. PMID 26546829.

- ^ Rader DJ, Cohen J, Hobbs HH (2003). "Monogenic hypercholesterolemia: new insights in pathogenesis and treatment". J. Clin. Invest. 111 (12): 1795–803. doi:10.1172/JCI18925. PMC 161432

. PMID 12813012.

. PMID 12813012. - ^ Marais AD, Blom DJ, Firth JC (January 2002). "Statins in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia". Curr Atheroscler Rep. 4 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1007/s11883-002-0058-7. PMID 11772418.

- ^ Liu, YH; Liu, Y; Duan, CY (September 2014). "Statins for the Prevention of Contrast-Induced Nephropathy After Coronary Angiography/Percutaneous Interventions: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.". J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 20: 181–192. doi:10.1177/1074248414549462. PMID 25193735.

- ^ table adapted from the following source, but check individual references for technical explanations

- Consumer Reports; Drug Effectiveness Review Project (March 2013), "Evaluating statin drugs to treat High Cholesterol and Heart Disease: Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF), Best Buy Drugs, Consumer Reports, p. 9, retrieved 27 March 2013

- ^ Asberg A (2003). "Interactions between cyclosporin and lipid-lowering drugs: Implications for organ transplant recipients". Drugs. 63 (4): 367–378. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363040-00003. PMID 12558459.

- ^ Food and Drug Administration (1 March 2012). "Drug Safety and Availability; FDA Drug Safety Communication: Interactions between certain HIV or hepatitis C drugs and cholesterol-lowering statin drugs can increase the risk of muscle injury". fda.gov. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Bellosta S, Paoletti R, Corsini A (2004). "Safety of Statins: Focus on Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Drug Interactions". Circulation. 109 (23_suppl_1): III–I50. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000131519.15067.1f. PMID 15198967.

- ^ Omar MA, Wilson JP (2002). "FDA Adverse Event Reports on Statin-Associated Rhabdomyolysis". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (2): 288–295. doi:10.1345/aph.1A289. PMID 11847951.

- ^ Armitage J (2007). "The safety of statins in clinical practice". The Lancet. 370 (9601): 1781–1790. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60716-8. PMID 17559928.

- ^ Naci H, Brugts J, Ades T (July 2013). "Comparative tolerability and harms of individual statins: a study-level network meta-analysis of 246 955 participants from 135 randomized, controlled trials". Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 6 (4): 390–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000071. PMID 23838105.

- ^ Bellosta, S; Corsini, A (2012). "Statin drug interactions and related adverse reactions". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 11 (6): 933–46. doi:10.1517/14740338.2012.712959. PMID 22866966.

- ^ Collins, Rory; Reith, Christina; Emberson, Jonathan; Armitage, Jane; Baigent, Colin; Blackwell, Lisa; Blumenthal, Roger; Danesh, John; Smith, George Davey; DeMets, David; Evans, Stephen; Law, Malcolm; MacMahon, Stephen; Martin, Seth; Neal, Bruce; Poulter, Neil; Preiss, David; Ridker, Paul; Roberts, Ian; Rodgers, Anthony; Sandercock, Peter; Schulz, Kenneth; Sever, Peter; Simes, John; Smeeth, Liam; Wald, Nicholas; Yusuf, Salim; Peto, Richard (September 2016). "Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy". The Lancet. 388: 2532–2561. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5. PMID 27616593.

- ^ Brault, Marilyne; Ray, Jessica; Gomez, Yessica-Haydee; Mantzoros, Christos S.; Daskalopoulou, Stella S. (2014-06-01). "Statin treatment and new-onset diabetes: a review of proposed mechanisms". Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 63 (6): 735–745. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2014.02.014. ISSN 1532-8600. PMID 24641882.

- ^ a b Golomb BA, Evans MA (2008). "Statin Adverse Effects: A Review of the Literature and Evidence for a Mitochondrial Mechanism". Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 8 (6): 373–418. doi:10.2165/0129784-200808060-00004. PMC 2849981

. PMID 19159124.

. PMID 19159124. - ^ Kmietowicz Z (2014). "New analysis fuels debate on merits of prescribing statins to low risk people". BMJ. 348: g2370. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2370. PMID 24671956.

- ^ Wise J (2014). "Open letter raises concerns about NICE guidance on statins". BMJ. 348: g3937. doi:10.1136/bmj.g3937. PMID 24920699.

- ^ Gøtzsche PC (2014). "Muscular adverse effects are common with statins". BMJ. 348: g3724. doi:10.1136/bmj.g3724. PMID 24920687.

- ^ Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, et al. (2013). "Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1: CD004816. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5. PMID 23440795.

- ^ Silva MA, Swanson AC, Gandhi PJ, Tataronis GR (January 2006). "Statin-related adverse events: a meta-analysis". Clin Ther. 28 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.01.005. PMID 16490577.

- ^ a b Mancini GB, Baker S, Bergeron J, et al. (2011). "Diagnosis, prevention, and management of statin adverse effects and intolerance: proceedings of a Canadian Working Group Consensus Conference". Can J Cardiol. 27 (5): 635–62. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2011.05.007. PMID 21963058.

- ^ Finegold JA, Manisty CH, Goldacre B, Barron AJ, Francis DP (April 2014). "What proportion of symptomatic side effects in patients taking statins are genuinely caused by the drug? Systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials to aid individual patient choice". Eur J Prev Cardiol. 21 (4): 464–74. doi:10.1177/2047487314525531. PMID 24623264.

- ^ Jonathan McDonagh (October 27, 2014). "Statin-Related Cognitive Impairment in the Real World: You'll Live Longer, but You Might Not Like It". JAMA Intern Med. 174: 1889. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5376. PMID 25347692.

- ^ Url =http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm293330.htm

- ^ "www.accessdata.fda.gov" (PDF).

- ^ Mancini GB, Tashakkor AY, Baker S, et al. (December 2013). "Diagnosis, prevention, and management of statin adverse effects and intolerance: Canadian Working Group Consensus update". Can J Cardiol. 29 (12): 1553–68. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.09.023. PMID 24267801.

- ^ Richardson K, Schoen M, French B, Umscheid CA, Mitchell MD, Arnold SE, Heidenreich PA, Rader DJ, deGoma EM (Nov 19, 2013). "Statins and cognitive function: a systematic review.". Ann Intern Med. 159 (10): 688–97. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00007. PMID 24247674.

- ^ Rull, Gurvinder; Henderson, Roger (2015-01-20). "Rhabdomyolysis and Other Causes of Myoglobinuria". Retrieved 2015-05-06.

- ^ Ghirlanda G, Oradei A, Manto A, Lippa S, Uccioli L, Caputo S, Greco AV, Littarru GP (1993). "Evidence of plasma CoQ10-lowering effect by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study". J Clin Pharmacol. 33 (3): 226–9. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb03948.x. PMID 8463436.

- ^ Marcoff L, Thompson PD (2007). "The role of coenzyme Q10 in statin-associated myopathy: a systematic review". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49 (23): 2231–7. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.049. PMID 17560286.

- ^ Link E; Parish S; Armitage J; Bowman L; Heath S; Matsuda F; Gut I; Lathrop M; Collins R (2008). "SLCO1B1 Variants and Statin-Induced Myopathy – A Genomewide Study". NEJM. 359 (8): 789–799. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. PMID 18650507.

- ^ a b Graham DJ, Staffa JA, Shatin D, Andrade SE, Schech SD, La Grenade L, Gurwitz JH, Chan KA, Goodman MJ, Platt R (2004). "Incidence of hospitalized rhabdomyolysis in patients treated with lipid-lowering drugs" (PDF). JAMA. 292 (21): 2585–90. doi:10.1001/jama.292.21.2585. PMID 15572716.

- ^ a b Hanai J, Cao P, Tanksale P, Imamura S, Koshimizu E, Zhao J, Kishi S, Yamashita M, Phillips PS, Sukhatme VP, Lecker SH (2007). "The muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1/MAFbx mediates statin-induced muscle toxicity". J. Clin. Invest. 117 (12): 3940–51. doi:10.1172/JCI32741. PMC 2066198

. PMID 17992259.

. PMID 17992259. - ^ Teichtahl, AJ; Brady, SR; Urquhart, DM; Wluka, AE; Wang, Y; Shaw, JE; Cicuttini, FM (15 February 2016). "Statins and tendinopathy: a systematic review.". The Medical journal of Australia. 204 (3): 115–21. doi:10.5694/mja15.00806. PMID 26866552.

- ^ Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, Seshasai SR, McMurray JJ, Freeman DJ, Jukema JW, Macfarlane PW, Packard CJ, Stott DJ, Westendorp RG, Shepherd J, Davis BR, Pressel SL, Marchioli R, Marfisi RM, Maggioni AP, Tavazzi L, Tognoni G, Kjekshus J, Pedersen TR, Cook TJ, Gotto AM, Clearfield MB, Downs JR, Nakamura H, Ohashi Y, Mizuno K, Ray KK, Ford I (2010). "Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials". Lancet. 375 (9716): 735–42. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6. PMID 20167359.

- ^ Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, Murphy SA, Ho JE, Waters DD, DeMicco DA, Barter P, Cannon CP, Sabatine MS, Braunwald E, Kastelein JJ, de Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Pedersen TR, Tikkanen MJ, Sattar N, Ray KK (2011). "Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderate-dose statin therapy: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 305 (24): 2556–64. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.860. PMID 21693744.

- ^ Jukema JW, Cannon CP, de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG, Trompet S (Sep 4, 2012). "The controversies of statin therapy: weighing the evidence.". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 60 (10): 875–81. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.007. PMID 22902202.

- ^ Rutishauser J (Nov 21, 2011). "Statins in clinical medicine.". Swiss Medical Weekly. 141: w13310. doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13310. PMID 22101921.

- ^ Alsheikh-Ali AA, Maddukuri PV, Han H, Karas RH (2007). "Effect of the Magnitude of Lipid Lowering on Risk of Elevated Liver Enzymes, Rhabdomyolysis, and Cancer: Insights from Large Randomized Statin Trials". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 50 (5): 409–418. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.073. PMID 17662392.

- ^ Dale KM, Coleman CI, Henyan NN, Kluger J, White CM (2006). "Statins and cancer risk: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 295 (1): 74–80. doi:10.1001/jama.295.1.74. PMID 16391219.

- ^ Alsheikh-Ali AA, Karas RH (March 2009). "The relationship of statins to rhabdomyolysis, malignancy, and hepatic toxicity: evidence from clinical trials.". Current atherosclerosis reports. 11 (2): 100–4. doi:10.1007/s11883-009-0016-8. PMID 19228482.

- ^ Singh S, Singh AG, Singh PP, Murad MH, Iyer PG (June 2013). "Statins are associated with reduced risk of esophageal cancer, particularly in patients with Barrett's esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis.". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 11 (6): 620–9. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.036. PMID 23357487.

- ^ Liu Y, Tang W, Wang J, Xie L, Li T, He Y, Deng Y, Peng Q, Li S, Qin X (Nov 22, 2013). "Association between statin use and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 42 studies.". Cancer causes & control : CCC. 25 (2): 237–49. doi:10.1007/s10552-013-0326-6. PMID 24265089.

- ^ Wu XD, Zeng K, Xue FQ, Chen JH, Chen YQ (October 2013). "Statins are associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis.". European journal of clinical pharmacology. 69 (10): 1855–60. doi:10.1007/s00228-013-1547-z. PMID 23748751.

- ^ Singh PP, Singh S (July 2013). "Statins are associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis.". Annals of Oncology. 24 (7): 1721–30. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt150. PMID 23599253.

- ^ Pradelli D, Soranna D, Scotti L, Zambon A, Catapano A, Mancia G, La Vecchia C, Corrao G (May 2013). "Statins and primary liver cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies.". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 22 (3): 229–34. doi:10.1097/cej.0b013e328358761a. PMID 23010949.

- ^ Zhang Y, Zang T (2013). "Association between statin usage and prostate cancer prevention: a refined meta-analysis based on literature from the years 2005–2010.". Urologia internationalis. 90 (3): 259–62. doi:10.1159/000341977. PMID 23052323.

- ^ Bansal D, Undela K, D'Cruz S, Schifano F (2012). "Statin use and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies.". PLoS ONE. 7 (10): e46691. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046691. PMC 3462187

. PMID 23049713.

. PMID 23049713. - ^ Tan M, Song X, Zhang G, Peng A, Li X, Li M, Liu Y, Wang C (2013). "Statins and the risk of lung cancer: a meta-analysis.". PLoS ONE. 8 (2): e57349. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057349. PMC 3585354

. PMID 23468972.

. PMID 23468972. - ^ Zhang XL, Liu M, Qian J, Zheng JH, Zhang XP, Guo CC, Geng J, Peng B, Che JP, Wu Y (Jul 23, 2013). "Statin use and risk of kidney cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized trials.". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 77 (3): 458–465. doi:10.1111/bcp.12210. PMID 23879311.

- ^ Undela K, Srikanth V, Bansal D (August 2012). "Statin use and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies.". Breast cancer research and treatment. 135 (1): 261–9. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-2154-x. PMID 22806241.

- ^ Cui X, Xie Y, Chen M, Li J, Liao X, Shen J, Shi M, Li W, Zheng H, Jiang B (July 2012). "Statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis.". Cancer causes & control : CCC. 23 (7): 1099–111. doi:10.1007/s10552-012-9979-9. PMID 22562222.

- ^ Zhang XL, Geng J, Zhang XP, Peng B, Che JP, Yan Y, Wang GC, Xia SQ, Wu Y, Zheng JH (April 2013). "Statin use and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis.". Cancer causes & control : CCC. 24 (4): 769–76. doi:10.1007/s10552-013-0159-3. PMID 23361339.

- ^ Mayo clinic: article on interference between grapefruit and medication

- ^ Kane GC, Lipsky JJ (2000). "Drug-grapefruit juice interactions". Mayo Clin. Proc. 75 (9): 933–42. doi:10.4065/75.9.933. PMID 10994829.

- ^ Reamy BV, Stephens MB (July 2007). "The grapefruit-drug interaction debate: role of statins". Am Fam Physician. 76 (2): 190, 192; author reply 192. PMID 17695563.

- ^ FDA Website Statins and HIV or Hepatitis C Drugs: Drug Safety Communication – Interaction Increases Risk of Muscle Injury

- ^ Istvan ES, Deisenhofer J (2001). "Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase". Science. 292 (5519): 1160–4. doi:10.1126/science.1059344. PMID 11349148.

- ^ a b Endo A (1 November 1992). "The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors" (PDF). J. Lipid Res. 33 (11): 1569–82. PMID 1464741.

- ^ Miettinen TA (March 1982). "Diurnal variation of cholesterol precursors squalene and methyl sterols in human plasma lipoproteins". Journal of Lipid Research. 23 (3): 466–73. PMID 7200504.

- ^ Saito Y, Yoshida S, Nakaya N, Hata Y, Goto Y (Jul–Aug 1991). "Comparison between morning and evening doses of simvastatin in hyperlipidemic subjects. A double-blind comparative study". Arterioscler Thromb. 11 (4): 816–26. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.11.4.816. PMID 2065035.

- ^ Wallace A, Chinn D, Rubin G (4 October 2003). "Taking simvastatin in the morning compared with in the evening: randomised controlled trial". British Medical Journal. 327 (7418): 788. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7418.788. PMC 214096

. PMID 14525878.

. PMID 14525878. - ^ Cilla DD, Gibson DM, Whitfield LR, Sedman AJ (July 1996). "Pharmacodynamic effects and pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin after administration to normocholesterolemic subjects in the morning and evening". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 36 (7): 604–9. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04224.x. PMID 8844442.

- ^ Ma PT, Gil G, Südhof TC, Bilheimer DW, Goldstein JL, Brown MS (1986). "Mevinolin, an inhibitor of cholesterol synthesis, induces mRNA for low density lipoprotein receptor in livers of hamsters and rabbits" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83 (21): 8370–4. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.8370M. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.21.8370. PMC 386930

. PMID 3464957.

. PMID 3464957. - ^ Laufs U; Custodis F; Böhm M (2006). "HMGCoA reductase inhibitors in chronic heart failure: potential mechanisms of benefit and risk". Drugs. 66 (2): 145–154. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666020-00002. PMID 16451090.

- ^ Greenwood J, Steinman L, Zamvil SS (May 2006). "Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation". Nat Rev Immunol. 6 (5): 358–70. doi:10.1038/nri1839. PMID 16639429.

- ^ Lahera V, Goicoechea M, de Vinuesa SG, Miana M, de las Heras N, Cachofeiro V, Luño J (2007). "Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation in atherosclerosis: beneficial effects of statins". Curr Med Chem. 14 (2): 243–8. doi:10.2174/092986707779313381. PMID 17266583.

- ^ Blum A, Shamburek R (April 2009). "The pleiotropic effects of statins on endothelial function, vascular inflammation, immunomodulation and thrombogenesis". Atherosclerosis. 203 (2): 325–30. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.022. PMID 18834985.

- ^ Porter KE, Turner NA (2011). "Statins and myocardial remodelling: cell and molecular pathways". Expert Rev Mol Med. 13 (e22). doi:10.1017/S1462399411001931. PMID 21718586.

- ^ Sawada N; Liao JK (2014). "Rho/Rho associated coiled coil forming kinase pathway as therapeutic targets for statins in atherosclerosis". Antioxid Redox Signal. 20 (8): 1251–67. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5524. PMID 23919640.

- ^ "Questions Remain in Cholesterol Research". MedPageToday. 15 August 2014.

- ^ Thurnher M, Nussbaumer O, Gruenbacher G (Jul 2012). "Novel aspects of mevalonate pathway inhibitors as antitumor agents". Clin Cancer Res. 18 (13): 3524–31. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0489. PMID 22529099.

- ^ Norata GD, Tibolla G, Catapano AL (Oct 2014). "Statins and skeletal muscles toxicity: from clinical trials to everyday practice.". Pharmacol Res. 88: 107–13. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2014.04.012. PMID 24835295.

- ^ Kowluru A (Jan 2008). "Protein prenylation in glucose-induced insulin secretion from the pancreatic islet beta cell: a perspective". J Cell Mol Med. 12 (1): 164–73. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00168.x. PMID 18053094.

- ^ Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, Davignon J, Erbel R, Fruchart JC, Tardif JC, Schoenhagen P, Crowe T, Cain V, Wolski K, Goormastic M, Tuzcu EM (2006). "Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial". JAMA. 295 (13): 1556–65. doi:10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002. PMID 16533939.

- ^ Furberg CD (19 January 1999). "Natural Statins and Stroke Risk". Circulation. 99 (2): 185–188. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.99.2.185. PMID 9892578.

- ^ Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT, Glynn RJ (2008). "Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein" (PDF). NEJM. 359 (21): 2195–207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. PMID 18997196.

- ^ Kones R (2010). "Rosuvastatin, inflammation, C-reactive protein, JUPITER, and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease--a perspective". Drug Des Devel Ther. 4: 383–413. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S10812. PMC 3023269

. PMID 21267417.

. PMID 21267417. - ^ Ferdinand KC (February 2011). "Are cardiovascular benefits in statin lipid effects dependent on baseline lipid levels?". Curr Atheroscler Rep. 13 (1): 64–72. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0149-9. PMID 21104458.

- ^ Devaraj S, Siegel D, Jialal I (February 2011). "Statin therapy in metabolic syndrome and hypertension post-JUPITER: what is the value of CRP?". Curr Atheroscler Rep. 13 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0143-2. PMC 3018293

. PMID 21046291.

. PMID 21046291. - ^ Safety of Statins: Focus on Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Drug Interactions" Circulation 2004:109:III-50-IIIi-57

- ^ "Metabolism of cerivastatin by human liver microsomes in vitro. Characterization of primary metabolic pathways and of cytochrome P450 isozymes involved". Drug Metab Dispos. 25 (3): 321–31. Mar 1997.

- ^ "Comparison of Cytochrome P-450-Dependent Metabolism and Drug Interactions of the 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors Lovastatin and Pravastatin in the Liver". DMD. 27 (2): 173–179. 1999.

- ^ Shepherd J, Hunninghake DB, Barter P, McKenney JM, Hutchinson HG (2003). "Guidelines for lowering lipids to reduce coronary artery disease risk: a comparison of rosuvastatin with atorvastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin for achieving lipid-lowering goals". Am. J. Cardiol. 91 (5A): 11C–17C; discussion 17C–19C. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00004-3. PMID 12646338.

- ^ Liu J, Zhang J, Shi Y, Grimsgaard S, Alraek T, Fønnebø V (2006). "Chinese red yeast rice (Monascus purpureus) for primary hyperlipidemia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Chin Med. 1 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/1749-8546-1-4. PMC 1761143

. PMID 17302963.

. PMID 17302963. - ^ Brown Alian G.; Smale Terry C.; King Trevor J.; Hasenkamp Rainer; Thompson Ronald H. (1976). "Crystal and Molecular Structure of Compactin, a New Antifungal Metabolite from Penicillium brevicompactum". J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1976: 1165–1170. doi:10.1039/P19760001165. PMID 945291.

- ^ Steinberg, Daniel. The Cholesterol Wars: The Skeptics vs. The Preponderance of Evidence. Academic Press, 2007, pp. 6–9.

- ^ "Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S)". Lancet. 344 (8934): 1383–9. November 1994. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90566-5. PMID 7968073.

- ^ "National Inventors Hall of Fame Honors 2012 Inductees". PRNewswire. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- ^ "How One Scientist Intrigued by Molds Found First Statin". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- ^ Wolozin B, Wang SW, Li NC, Lee A, Lee TA, Kazis LE (July 19, 2007). "Simvastatin is associated with a reduced incidence of dementia and Parkinson's disease". BMC Medicine. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-5-20. PMC 1955446

. PMID 17640385.

. PMID 17640385.

- ^ Khurana V, Bejjanki HR, Caldito G, Owens MW (May 2007). "Statins reduce the risk of lung cancer in humans: a large case-control study of US veterans". Chest. 131 (5): 1282–1288. doi:10.1378/chest.06-0931. PMID 17494779.[dead link]

- ^ Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE, Grady LM (June 2006). "Statin use and incident nuclear cataract". JAMA. 295 (23): 2752–8. doi:10.1001/jama.295.23.2752. PMID 16788130.

- ^ Golomb BA, Dimsdale JE, White HL, Ritchie JB, Criqui MH (April 2008). "Reduction in blood pressure with statins: results from the UCSD Statin Study, a randomized trial". Arch. Intern. Med. 168 (7): 721–7. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.7.721. PMID 18413554.

- ^ Drapala, A; Sikora, M; Ufnal, M (Sep 2014). "Statins, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and hypertension - a tale of another beneficial effect of statins.". Journal of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system : JRAAS. 15 (3): 250–8. doi:10.1177/1470320314531058. PMID 25037529.

- ^ Mondul AM, Han M, Humphreys EB, Meinhold CL, Walsh PC, Platz EA (February 2011). "Association of statin use with pathological tumor characteristics and prostate cancer recurrence after surgery". Journal of Urology. 185 (4): 1268–1273. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.089. PMC 3584560

. PMID 21334020.

. PMID 21334020.

***

The secret behind Donald Trump's hair 01:59, CNN (February 3, 2017)

The President's use of this medication was not disclosed by his doctor during campaign

Propecia is a low dose formulation of finasteride used to promote hair growth

President Trump is taking a prostate drug often prescribed for hair loss, his physician Dr. Harold N. Bornstein told the New York Times in an interview published Wednesday. He also made a point of stating that the President has all of his hair.

The New York City gastroenterologist also said the President is taking antibiotics to control rosacea, a skin condition that causes redness.

A senior White House official says Bornstein did not have Trump's permission to speak about his health to the Times.

The physician told the Times he has had no contact with his patient since Trump became president. Trump had visited his office every year since 1980 for annual checkups, colonoscopies and other routine tests.

During the campaign, Trump's longtime physician disclosed only that he was taking rosuvastatin and low-dose aspirin to reduce his risk of heart attack.

Bornstein came under scrutiny for a letter he wrote describing Trump's physical health that concluded, "If elected, Mr. Trump, I can state unequivocally, will be the healthiest individual ever elected to the presidency."

Other doctors found the letter's conclusion unprofessional and said Bornstein had used strange wording and medically incorrect terms when referring to his high-profile patient. Bornstein told CNN in September that he was rushed for time and had patients to see when writing the letter.

What is Propecia?

Propecia is a lower-dose formulation of finasteride that is prescribed to men with enlarged prostate glands under the brand name Proscar.

Originally, the Food and Drug Administration approved finasteride 5 mg (Proscar) in 1992 for the treatment of "bothersome symptoms in men" with an enlarged prostate, which is also referred to as benign prostatic hyperplasia. At that time, the FDA also approved Proscar to reduce the need for surgery related to an enlarged prostate and possible urine retention.

In 1997, the agency approved a lower-dose formulation of finasteride (Propecia) for the treatment of male pattern hair loss, a gradual thinning that leads to either a receding hairline or balding on the top of the head. The FDA does not permit Propecia for treating hair loss in women or children.

"It is a very common medication," said Dr. Louis Kavoussi, chairman of urology at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, NY. He added that finasteride has been around for decades, so its long-term safety has been demonstrated.

The drug, which blocks the body's production of male hormones, is in a class of medications called 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.

"The effectiveness varies," said Kavoussi, who has no ties to Merck or the companies that make generic versions of finasteride. Though some men who take it for hair loss find it "very effective," others do not. "Same for prostate," he said. "Some men gain quite a bit of symptom relief, other men more modest. It depends on the patient."

Possible side effects of the finasteride include decreased libido, problems with erection and ejaculation, pain in the testicles and depression. According to drugmaker Merck's prescribing information, patients taking the drug should promptly notify their doctor if they experience changes in their breasts, rash, itching, hives, swelling of the face or hands, or difficulty breathing or swallowing.

According to Kavoussi, "most men tolerate it pretty well." Those who do get side effects simply stop taking the medicine, and the effects resolve.

For some years, Merck has been a defendant in liability lawsuits regarding Propecia/Proscar.

About 1,370 lawsuits have been filed as of September 30 by people who claim that they have experienced persistent sexual side effects after cessation of treatment with Propecia and/or Proscar. About 50 of the plaintiffs also allege that the drug has caused or can cause prostate cancer, testicular cancer or male breast cancer.

Dr. Irwin Goldstein, founder of San Diego Sexual Medicine, is serving as an expert witness against Merck in the ligation, work for which he is being paid. He said people come to his clinic "from all over the world" for help with finasteride-associated symptoms.

Many patients experience "a sudden or significant change in libido," he said, while another common side effect is erectile dysfunction. Along with these sexual effects, Goldstein said the drug can cause problems with both mood and cognition, including harmful effects on memory and decision-making.

Some patients believe they suffer from "post-finasteride syndrome," in which their symptoms continue after they stop taking the drug.

As of March 2015, the syndrome is listed on the National Institutes of Health's Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center, with the disclaimer that this is not intended as "official recognition" of the syndrome. Still, the National Institutes of Health has sponsored studies, which are now underway, to better understand the effects of finasteride.

"You don't want people to shy away -- and that's the bad thing about lawsuits; people get the impression that something is very bad," Kavoussi said, adding, "it's helped a lot of men."

Merck listed 2015 sales of the drug at $183 million, down from a peak of $447 million in 2010. Other drug manufacturers began producing generic versions in 2013.

Efforts to contact Bornstein for comment have not been successful.

***

ROSACEA: DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

How do dermatologists diagnose rosacea?To diagnose rosacea, a dermatologist examines the skin and eyes. Your dermatologist also will ask questions.

How do dermatologists treat rosacea?

To treat rosacea, a dermatologist first finds all of the patient’s signs and symptoms of rosacea. This is crucial because different signs and symptoms need different treatment.

Treatment for the skin includes:

- Medicine that is applied to the rosacea.

- Sunscreen (wearing it every day can help prevent flare-ups).

- An emollient to help repair the skin.

- Lasers and other light treatments.

- Antibiotics (applied to the skin and pills).

Dermatologists can remove the thickening skin that appears on the nose and other parts of the face with:

- Lasers.

- Dermabrasion (procedure that removes skin).

- Electrocautery (procedure that sends electric current into the skin to treat it).

When rosacea affects the eyes, a dermatologist may give you instructions for washing the eyelids several times a day and a prescription for eye medicine.

Outcome

There is no cure for rosacea. People often have rosacea for years.

In one study, researchers asked 48 people who had seen a dermatologist for rosacea about their rosacea. More than half (52 percent) had rosacea that came and went. These people had had rosacea for an average of 13 years. The rest of the people (48 percent) had seen their rosacea clear. People who saw their rosacea clear had rosacea for an average of 9 years.

Some people have rosacea flare-ups for life. Treatment can prevent the rosacea from getting worse. Treatment also can reduce the acne-like breakouts, redness, and the number of flare-ups.

To get the best results, people with rosacea also should learn what triggers their rosacea, try to avoid these triggers, and follow a rosacea skin-care plan.

***

image from

***

U.S. Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump eats a pork chop at the Iowa State Fair during a campaign stop in Des Moines in 2015. (Jim Young/Reuters)

Donald Trump takes office Friday as the oldest incoming president in U.S. history — a burger-gobbling, exercise-averse 70-year-old who can expect to live 15 more years, according to actuarial data.

But unlike the fitness fanatic whom he follows into the White House, Trump apparently has never smoked tobacco. He doesn’t drink alcohol. And as a wealthy American, he has presumably spent much of his life with access to excellent health care.

Experts agree there is no reason why a healthy man in his 70s cannot carry out the demanding responsibilities of president of the United States, especially someone who has just been tested by the rigors of a 16-month campaign. Yet a person’s “healthspan” — the years he or she is healthy and free of serious disease — is a highly individual mix of genetics, nutrition, lifestyle, social support, access to care and more.

“The key thing is how any person lives with the stress,” said Gordon Lithgow, a professor of geroscience at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in California, which studies ways to increase healthspan. “Some people absolutely thrive on the edge of stress.”

By that measure, Trump will be severely tested. Presidents, who seem to age before our eyes, die earlier than their peers, according to a 1992 book, “The Mortal Presidency: Illness and Anguish in the White House,” that looked at 32 modern leaders. Author Robert Gilbert found that even as U.S. life expectancy rose sharply in the 20th century, 21 of 32 presidents died prematurely. His study did not include the four who were assassinated.

Given that the 45th president will be exposed to extraordinary stress levels, what else could affect his health and capabilities to respond to the challenges of office?

“I think the main thing is that the future is a lot less predictable when you’re 70 than when you’re 40 or 50,” said Steve Austad, scientific director of the American Federation for Aging Research. “He could be fine 10 years after his presidency, or he could be in bad shape a year from now.”

Trump has released only limited information about the measures of his own health. In an email on Tuesday, spokeswoman Hope Hicks said there were no plans to give out more. “The President-elect is extremely healthy,” she added, “with excellent genes and great energy and stamina.”

But research shows that the chances of acquiring three diseases simultaneously rises ten-fold between ages 70 and 80, then ten-fold again during the following decade of life, said Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

“I think we all realize that humans age at different rates,” Barzilai said. “Seventy means nothing to me. It can be very young, and it can be very old.”

Barzilai said his first question would be how long Trump’s parents lived, particularly his mother. Eighty-five of every 100 centenarians are female, and the influence of long-lived women’s genes on their children is evident, he said.

Trump’s parents did well for people born near the turn of the last century. His mother, Mary Ann McLeod Trump, was 88 when she died. His father, Fred, died at 93 after suffering from Alzheimer’s disease for about five years.

The risk of Alzheimer’s, which eventually afflicted the second-oldest incoming president, Ronald Reagan, doubles every five years after age 60, said Valter Longo, professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California’s Leonard Davis School of Gerontology. Trump’s family history puts him at greater risk, though.

The roles of diet and physical activity have long been acknowledged in healthful aging, often in protecting against heart disease and cancer, the two biggest killersof Americans. On these issues, there is some pertinent information from the president-elect’s longtime doctor.

In a one-page letter in September, New York gastroenterologist Harold Bornstein said there was no history of “premature” cancer or heart disease in Trump’s family. He said the president-elect is 6-foot-3 and weighs 236 pounds, which qualifies him as borderline obese. Trump has acknowledged a poor diet heavy on fast food — McDonald’s hamburgers are a favorite — and admits he would like to lose some weight.

Bornstein’s letter said Trump takes a statin to lower his cholesterol. So it is difficult to judge his cholesterol level of 169, his high-density lipoprotein level of 63 or his low-density lipoprotein level of 94. All are in the normal range. Trump also takes a low dose of aspirin, the letter noted.

Trump’s blood pressure of 116 over 70 was normal, as was his blood-sugar level, Bornstein wrote. “His liver function and thyroid function tests are all within the normal range,” he added, and “his last colonoscopy was performed on July 10, 2013 which was normal and revealed no polyps.”

Trump’s latest electrocardiogram and chest X-ray were conducted in April 2016 and also were “normal,” according to Bornstein.

(Many presidential candidates have publicly shared more information about their health, but in declining to release his full medical records as a candidate, Trump was in some good Democratic company. Bill Clinton refused to do so during his 1992 and 1996 campaigns. John F. Kennedy, who traded on his seeming vitality in his 1960 race against Richard Nixon, hid his Addison’s disease, an adrenaline deficiency, during the campaign.)

Trump appears to get little exercise other than an occasional round of golf — a serious mistake, according to most health authorities. Research continues to indicate the protective benefits of physical activity for everything from declining cognition to reduced muscle strength. Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has called exercise the closest thing to “a magic bullet” known in health care.

“Exercise is the best anti-aging medicine,” said Eric Verdin, chief executive of the Buck Institute.

Famously proud of his stamina, the next president also ignores another piece of critical health advice: the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s recommendation that adults get about seven hours of sleep per night. On the campaign trail, Trump has said he needs only about four hours.

Barzilai said that while some individuals can remain healthy on a few hours of sleep nightly, they are exceedingly rare. Most people become “metabolically compromised,” insulin-resistant and ineffective at absorbing nutrients, not to mention cranky, he said.

Trump’s early-morning Twitter posts are among his most emotional, Barzilai noted. “I would say there is evidence, at least by tweet, that Trump is not sleeping enough,” he said.

Perhaps one of Trump’s greatest health advantages is his socioeconomic status. A child of affluence, he has never had to endure poverty or anything close to it. Overwhelming evidence exists that the poor face greater risk of illness and death than the wealthy. And prior to the Affordable Care Act, which expanded health insurance to millions of lower-income Americans, they also faced greater difficulty obtaining health insurance.

“People who live and work in low socioeconomic circumstances are at increased risk for mortality, morbidity, unhealthy behaviors, reduced access to health care, and inadequate quality of care,” the CDC reported in 2011.

Trump, by contrast, has reaped the health benefits of his birth and circumstance.

“He’s rich and well-educated,” Austad said, “and those things are almost miracle drugs.”

Michael Kranish contributed to this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment