From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

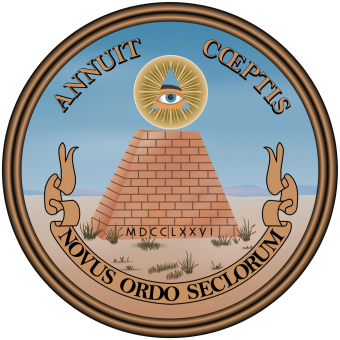

E pluribus unum (/ˈiː ˈpluːrᵻbəs ˈuːnəm/; Latin: [ˈeː ˈpluːrɪbʊs ˈuːnũː])—Latin for "Out of many, one"[1][2] (alternatively translated as "One out of many"[3] or "One from many")[4]— is a 13-letter traditional motto of the United States of America, appearing on the Great Seal along with Annuit cœptis (Latin for "He approves the undertaking") and Novus ordo seclorum (Latin for "New order of the ages"), and adopted by an Act of Congress in 1782.[2] Never codified by law, E Pluribus Unum was considered a de facto motto of the United States[5] until 1956 when the United States Congress passed an act (H. J. Resolution 396), adopting "In God We Trust" as the official motto.[6]

Contents

[hide]Origins[edit]

The 13-letter motto was suggested in 1776 by Pierre Eugene du Simitiere to the committee responsible for developing the seal. At the time of the American Revolution, the exact phrase appeared prominently on the title page of every issue of a popular periodical, The Gentleman's Magazine,[7][8] which collected articles from many sources into one "magazine". This in turn can be traced back to the London-based Huguenot Peter Anthony Motteux, who used the adage for his The Gentleman's Journal, or the Monthly Miscellany (1692-1694). The phrase is similar to a Latin translation of a variation of Heraclitus's 10th fragment, "The one is made up of all things, and all things issue from the one." A variant of the phrase was used in Moretum, a poem attributed to Virgil but with the actual author unknown, describing (on the surface at least) the making of moretum, a kind of herb and cheese spread related to modern pesto. In the poem text, color est e pluribus unus describes the blending of colors into one. St Augustine used the non-truncated variant of the phrase, ex pluribus unum, in his Confessions (e is the form of the Latin preposition ex that regularly appears before words beginning with a consonant). But it seems more likely that the phrase refers to Cicero's paraphrase of Pythagoras in his De Officiis, as part of his discussion of basic family and social bonds as the origin of societies and states: "When each person loves the other as much as himself, it makes one out of many (unus fiat ex pluribus), as Pythagoras wishes things to be in friendship."[9]

While Annuit cœptis ("He favors our undertakings") and Novus ordo seclorum ("New order of the ages") appear on the reverse side of the great seal, E pluribus unum appears on the obverse side of the seal (Designed by Charles Thomson), the image of which is used as the national emblem of the United States, and appears on official documents such as passports. It also appears on the seal of the President and in the seals of the Vice President of the United States, of the United States Congress, of the United States House of Representatives, of the United States Senate and on the seal of the United States Supreme Court.

Usage on coins[edit]

| Dime E pluribus unum engraving. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse: Portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt, year and US national motto (In God We Trust) | Reverse: E pluribus unum, olive branch, torch and oak branch, face-value and country. |

| Total 86,408,282,060 coins minted from 1965 to 2015. | |

The first coins with E pluribus unum were dated 1786 and struck under the authorization of the State of New Jersey by Thomas Goadsby and Albion Cox in Rahway, New Jersey.[10] The motto had no New Jersey linkage but was likely an available die that had been created by Walter Mould the previous year for a failed federal coinage proposal.[11]Walter Mould was also authorized by New Jersey to strike state coppers with this motto and did so beginning in early 1787 in Morristown, New Jersey. Lt. Col. Seth Read of Uxbridge, Massachusetts was said to have been instrumental in having E Pluribus Unum placed on US coins[12] Seth Read and his brother Joseph Read had been authorized by the Massachusetts General Court to mint coppers in 1786. In March 1786, Seth Read petitioned the Massachusetts General Court, both the House and the Senate, for a franchise to mint coins, both copper and silver, and "it was concurred".[13][14] E pluribus unum, written in capital letters, is included on most U.S. currency, with some exceptions to the letter spacing (such as the reverse of the dime). It is also embossed on the edge of the dollar coin. (See United States coinage and paper bills in circulation).

According to the U.S. Treasury, the motto E pluribus unum was first used on U.S. coinage in 1795, when the reverse of the half-eagle ($5 gold) coin presented the main features of the Great Seal of the United States. E pluribus unum is inscribed on the Great Seal's scroll. The motto was added to certain silver coins in 1798, and soon appeared on all of the coins made out of precious metals (gold and silver). In 1834, it was dropped from most of the gold coins to mark the change in the standard fineness of the coins. In 1837, it was dropped from the silver coins, marking the era of the Revised Mint Code. An Act of February 12, 1873 made the inscription a requirement of law upon the coins of the United States. E pluribus unum appears on all coins currently being manufactured, including the Presidential dollars that started being produced in 2007, where it is inscribed on the edge along with "In God We Trust" and the year and mint mark. After the Revolution, Rahway, New Jersey became the home of the first national mint to create a coin bearing the inscription E pluribus unum.

In a quality control error in early 2007 the Philadelphia Mint issued some one-dollar coins without E pluribus unum on the rim; these coins have already become collectibles.

The 2009 and new 2010 penny features a new design on the back, which displays the phrase E Pluribus unum in larger letters than in previous years.[1]

Other usages[edit]

- The motto E pluribus unum is used by Portuguese multi-sport club Benfica.

- This motto has also been used by the Scoutspataljon, a professional infantry battalion of the Estonian Defence Forces, since 1918.

- A variant of the motto, unum e pluribus is used by the Borough of Wokingham in Berkshire, United Kingdom.[15]

- E Pluribus Unum is a march by the composer Fred Jewell, written in 1917 during World War I.

- In 2001, following the September 11 attacks, the Ad Council and Texas ad agency GSD&M launched a famous public service announcement in which ethnically diverse people say "I am an American"; near the end of the PSA, a black screen shows and the phrase "E pluribus unum" is seen with the English translation underneath.[16]

- In the film The Wizard of Oz, the wizard gives the Scarecrow a diploma from the society of E Pluribus Unum.

- In the Twilight Zone episode "A Kind of a Stopwatch", a man receives a stopwatch that can stop time and is told, "remember, e pluribus unum" as he is given the watch.

- A short story collection by Theodore Sturgeon is called "E Pluribus Unicorn".

- American author David Foster Wallace reversed the motto in his 1993 essay "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction".

- "One Out of Many", a story about an Indian servant who travels to Washington with his employer, is included in V.S. Naipaul's novel In a Free State.

- The Marvel Comics character Foolkiller has calling cards that read "Foolkiller-e pluribus unum-Actions have Consequences."

- On the cork of a bottle of Monkey 47 Gin, a ring can be found that reads Ex Pluribus Unum.

- In Fate/Grand Order, E Pluribus Unum is one of the title chapters of the game's storyline that takes place in America.

- In an episode of Community (TV series), it is revealed that the Greendale Community College motto has been changed to 'E Pluribus Anus'.

See also[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to E pluribus unum. |

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ a b "e pluribus unum". treasury.gov. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ a b "E Pluribus Unum - Origin and Meaning of the Motto Carried by the American Eagle". Greatseal.com. 2011-11-28. Retrieved 2012-04-28.

- ^ "E Pluribus Unum". Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition. HarperCollins. Retrieved 2012-12-23.

- ^ "E Pluribus Unum". Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ H. John Lyke (September 6, 2012). What Would Our Founding Fathers Say?: How Today's Leaders Have Lost Their Way. iUniverse. p. 34.

- ^ https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/84/hjres396/text

- ^ "The Gentleman's Magazine". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle". 1747.

- ^ Cicero, Marcus Tullius. De Officiis. Liber I, Caput XVII.

- ^ Q. David Bowers. Whitman Encyclopedia of Colonial and Early American Coins. (Atlanta: Whitman Publishing, 2009) p. 129

- ^ Walter Breen. Complete Encyclopedia of US and Colonial Coins. (New York: FCI Press; Doubleday, 1998) p. 78

- ^ "Resource center faqs/coins accessed 2011-06-27". Treasury.gov. Retrieved 2012-03-03.

- ^ "Massachusetts Coppers 1787-1788: Introduction". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ March, 1786 Petition to mint Massachusetts Coppers, source Google books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-03-03.

- ^ "The Wokingham Borough Coat of Arms". Wokingham Borough. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

- ^ "I am an American". Ad Council/GSD&M. Retrieved 2013-01-03.

***

Daven Huskey, "What E Pluribus Unum Means," todayifoundout.com

Today I found out what “E pluribus unum” means.

E pluribus unum translates from Latin to English as follows: “e” meaning “from” or “out of”; “pluribus” being the ablative plural of the Latin for “more”; and “unum” meaning “one”. Thus, “E pluribus unum” simply means “from many, one” or “out of many, one”.

This Latin phrase was once the United States’ motto and can be found on the official seal of the U.S., among other places. It is thought to have been borrowed from the cover of a popular English periodical, The Gentlemen’s Magazine. This particular magazine was an extremely popular and influential men’s magazine among the elite and highly educated. While some of the content of the magazine was original, much of it was gathered from other sources (hence the word “magazine”, meaning “storehouse”, being used for the first time to describe a periodical). On the cover of this periodical, they’d generally include the phrase “E Pluribus Unum” signifying they gathered the content from a variety of sources.

Pierre-Eugène Ducimetière, the artistic consultant for the design of the official seal of the U.S., The Great Seal, suggested that this be placed on the seal, which it finally was in 1782 after three major revisions to the seal design. In this context, this was meant to signify the 13 colonies forming one unified government.

It was not long after this, in 1795, that E pluribus unum appeared on a $5 gold coin, which mimicked the U.S. seal in cover design. In 1798, the phrase was added to various silver coins and soon after to nearly all gold and silver coins, though this practice disappeared completely for a time. Finally on February 12, 1873, congress passed an act stipulating that the phrase must appear on all U.S. coins, which has continued to this day, excepting one mistake in 2007. That year the Philadelphia Mint accidentally released a batch of one dollar coins that didn’t have “E Pluribus Unum” on them. Obviously these coins are now collector’s items.

Bonus Facts:

E pluribus unum was officially replaced as the motto of the U.S. when, in 1956, Congress passed an act making “In God We Trust” the official motto.

E pluribus unum was officially replaced as the motto of the U.S. when, in 1956, Congress passed an act making “In God We Trust” the official motto.- On the reverse side of the Great Seal, while not actually cut on the physical seal itself, there is an unfinished pyramid with an eye in a triangle at the top, as you’ll see on the back of the one dollar bill since the 1930s. The pyramid is meant to signify strength and duration. The 13 levels signify the 13 original states. The eye is the “Eye of Providence” watching over the U.S. and supposedly approving of what it does.

- On the back of the seal, you’ll also find two mottoes, Annuit cœptis and Novus ordo seclorum. Annuit cœptis more or less means “approved of (our) undertakings”, combining with the Eye implying that Providence approves of what the U.S. does. The Novus ordo seclorum means “a new order of the ages”.

- This latter Novus ordo seclorum,”a new order of the ages”, is sometimes misinterpreted as “A New World Order” and is occasionally given sinister meaning in this way by Christian conspiracy theorists. In fact, this is just borrowed from Virgil and, ironically enough, some Christians, particularly in medieval times, interpreted this particularly poem as describing the coming of Christ, not a sinister government empowered by Satan. Charles Thomson, who was the Latin expert that proposed this phrase, stated to Congress that he meant this to signify “the beginning of the new American Era”.

- The idea that the Eye of Providence showed a Masonic influence in the formation of the United States isn’t accurate *looks disapprovingly at National Treasure*. The Eye wasn’t adopted by the Masons commonly until 1797. Where the Eye of Providence was significantly more popular at the time of the creation of the seal was among Christians, who had been using it since the Middle Ages. Further, the only known member of the Freemasons to be involved with the creation of the Seal, Benjamin Franklin, had every one of his seal design ideas rejected, excepting that there should be a back to the seal.

- The Eye of Providence is also often misinterpreted by certain Christian conspiracy theorists as being sinister in nature, with many suggesting it is the eye of Satan. In fact, as noted, it had long been used by Christians up to that point as the eye of God, so quite the opposite of sinister from the perspective of Christians at the time the seal was created.

- The oldest known case of the exact phrase E pluribus unum being used appeared in a briefly run periodical called Gentleman’s Journal, that ran from 1692-1694 and likely inspired The Gentlemen’s Magazine to use the phrase.

- The original committee to design the U.S. seal included Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams. They later consulted with Pierre-Eugène Ducimetière and their initial designs were not the ones ultimately used.

- Franklin’s design had Moses extending his hand over the sea, causing the waters to fall and overwhelm Pharaoh. He also had rays from a pillar of fire in the clouds landing upon Moses to signify God’s blessing. He then suggested the official U.S. motto be: “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God.” Once again demonstrating that by today’s standards, we’d call him an extremist terrorist.

- Jefferson’s design was also religious in nature, depicting the Children of Israel in the wilderness.

- Adams took a different route, depicting the “Judgment of Hercules”, where Hercules must choose between an easy, self-indulgent path or a difficult path where he must serve others.

- The final design for the seal borrowed from ideas developed by three different committees and was submitted to Congress for approval on June 20, 1782. The parts of the design included from the first committee was the E Pluribus Unum text; the Eye of Providence in a triangle; and the 1776 Roman numerals. The rest of their design was thrown out. The parts included from the second committee were the thirteen red and white stripes; the blue shield; the 13 stars surrounded by clouds; and the olive branch and arrows. The third committee contributed the eagle (not originally a bald eagle), and the unfinished pyramid. Charles Thomson then put it all together, switching the eagle to be a bald eagle, then adding the Latin phrases Annuit Cœptis and Novus Ordo Seclorum on the back.

- The official seal of the United States is kept by the Secretary of State and is used to authenticate various documents.

- So far the Great Seal has been replaced six times in the history of the U.S., with a new one engraved once the old one gets too worn to be used.

Expand for References

***

Both "In God We Trust" and "E Pluribus Unum" are firmly embedded in Americans' consciousness primarily because of their long, regular use on the nation's money. "E Pluribus Unum" has been an important part of American heraldry since before the ratification of the Constitution. It was incorporated into the Great Seal of the United States when that emblem was adopted in 1782 under the Articles of Confederation. Since 1796, it has been inscribed on most of the federal coinage and currency issued by Uncle Sam.

At no time, however, did it ever receive congressional recognition as the nation's official motto. That honor belongs instead to a phrase that is just as familiar, but holds much more personal meaning for most Americans: "In God We Trust."

"E Pluribus Unum" appealed to the Founding Fathers because it conveyed in a short, simple statement the way the 13 original colonies came together to form a single nation. Its English translation is "Out of many, one." But while the words are meaningful in explaining the nation's origin, they lack the emotional impact of the phrase "In God We Trust," which expresses Americans' deep, abiding faith that a higher power has guided the ship of state on its several-century journey through human history's often stormy seas.

On July 30, 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed legislation establishing "In God We Trust" as the nation's official motto. Sentiment favoring adoption of this motto had been building since the end of World War II, a conflict that — like the Civil War — caused many Americans to turn to a higher power for guidance, solace and hope. A year earlier, in 1955, Congress had approved the insertion of the words "under God" into the Pledge of Allegiance and mandated use of "In God We Trust" on all U.S. paper money.

Anyone who missed these well-publicized developments got a reminder on July 30, 2006 — the 50th anniversary of the original legislation — when President George W. Bush issued a proclamation reaffirming the status of "In God We Trust" as America's national motto and declaring anew its worthiness for that designation.

Yet, in the face of all this incontrovertible evidence, some federal officials have continued to maintain that "E Pluribus Unum" is the nation's official motto. Consider these examples, all from the 21st century:

• During construction of the Capitol Visitors Center, a three-level, 580,000-square-foot "waiting room" for tourists beneath the U.S. Capitol, a plaque was placed declaring "E Pluribus Unum" to be the official U.S. motto. The plaque has been replaced by one that correctly identifies "In God We Trust" as the national motto. But as of this spring, "E Pluribus Unum" was still being repeated throughout the introduction film shown to visitors taking the Capitol Tour, and "In God We Trust" reportedly wasn't mentioned in the film.

• "Coins for You — Old and New," a U.S. Treasury publication described as "A Starting Guide for Young Collectors," tells fledgling hobbyists that "many coin legends were written in Latin, formerly the international language of educated people. That's why one of our national mottoes, 'E Pluribus Unum,' is Latin." There is just one official national motto. It isn't "E Pluribus Unum." And it's readily understandable even to young Americans with little formal education — for it's written in English: "In God We Trust."[JB emphasis]

• Perhaps most alarmingly, President Obama showed similar ignorance about "In God We Trust" — and lack of appreciation for how meaningful it is for many Americans — in 2011, when he incorrectly identified "E Pluribus Unum" as the national motto, then dismissed congressional critics when they passed a resolution setting the record straight. The resolution was sponsored by Rep. Randy Forbes, R-Va. It supported and encouraged the display of the words "In God We Trust" in all public schools and government buildings.

Obama said the time devoted to drafting and passing the resolution could have been better spent hammering out a job creation bill.

President John Adams said, "It is religion and morality alone, which can establish the principles upon which freedom can securely stand."

As President Reagan warned, "If we ever forget that we're one nation under God, then we will be a nation gone under."

Mr. President, when all is said and done, one fact remains crystal clear: Out of all the potential selections for the nation's official motto, including "E Pluribus Unum," Congress chose only one: "In God We Trust."

***

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Journals/CJ/18/7/E_Pluribus_Unum*.html

[JB note: Written in 1923, before "In God We Trust" became the USA official motto.]

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Journals/CJ/18/7/E_Pluribus_Unum*.html

[JB note: Written in 1923, before "In God We Trust" became the USA official motto.]

E PLURIBUS UNUM

By Monroe E. Deutsch

University of California

University of California

An American cannot fail to have at least some interest in the phrase E Pluribus Unum; it meets him in many different places as an official expression of our national unity. What was its source? How did it come to be employed as the motto of the United States?aThese are the questions which this paper will endeavor to answer.

E Pluribus Unum was first used as an official motto of the United States when it was adopted as part of the Great Seal of our nation. It is necessary, therefore, in making an investigation of the history of the phrase to devote attention first to the steps that led to the adoption of our national seal.

Late on the afternoon of July 4, 1776 (a day famous in the annals of our country), the following resolution was adopted by the Continental Congress: "Resolved, that Dr. Franklin, Mr. J. Adams and Mr. Jefferson be a committee to prepare a device for a Seal of the United States of America." These are illustrious names in the history of our nation; it will be recalled that the men designated were the three leading members of the committee of five that had drawn up the Declaration. The committee made its report on August 20, 1776,1 a month and a half after its appointment. In this, the first recommendation concerning our national seal, appears the proposal: "Motto: E Pluribus Unum."

It should be said at this point that it is not the intention of this paper to trace the history of the various elements in our seal, but merely to follow the fortunes of our motto.

No action was taken on this report other than to lay it upon the p388table. In the years that followed, the matter of a seal was revived at intervals, and, in the course of the discussion, two new committees in turn were charged with the problem. The second definite proposal was not made until May 10, 1780; E Pluribus Unum had disappeared, the motto on the obverse being Bello vel Paci and on the reverse virtute perennis. This report, read May 17, was recommitted.

Again the decision as to our national seal restored, this time until May, 1782, when the third committee was appointed. They called upon the assistance of William Barton of Philadelphia, who had been a student of heraldry. In neither of the designs submitted by Barton did E Pluribus Unum appear. His second design was adopted by the committee and submitted as its recommendation on May 9, 1782. Congress did not, however, adopt it, but on June 13 referred the matter to Charles Thomson, its secretary; he proceeded energetically to work, and exactly one week later (June 20, 1782) our national seal was adopted.

Thomson modified Barton's second design, the one which the committee had formally recommended to Congress. For the reverse he adopted Barton's device, but changed the mottoes to Audacibus annue coeptis ("Favor the bold attempts"), Virgil, Aeneid IX.625 andGeorgics I.40, and Magnus ab integro seclorum nascitur ordo ("The great series of ages begins anew"), Virgil, Eclogue IV.5. The reverse (which is the only part of the seal now in use) differed in almost all respects from Barton's, and on this Thomson restored E Pluribus Unum. Barton made certain minor changes before the report was presented, and in this report, dated June 19, 1782, the mottoes on the reverse were curtailed to Annuit Coeptis and Novus Ordo Seclorum.

We find, therefore, that in the report of the first committee presented August 20, 1776, E Pluribus Unum appeared as a motto; it disappeared from all subsequent proposals for the seal until Charles Thomson, Secretary of Congress, restored it between June 13 and June 20, 1782, on which date our seal was adopted. Possibly the attentive secretary had been impressed by the first motto possessed, and when the matter was assigned to him, restored it.

p389It is, accordingly, necessary to return to the report of the first committee, composed of Franklin, Adams, and Jefferson, and endeavor to ascertain how the phrase came to appear in that report. There is extant an interesting letter from John Adams to his wife, dated Philadelphia, 14 August, 1776,2 which throws considerable light on the work of that committee. It will be noted that the letter was written while the committee was in the midst of its labors. The pertinent passages are as follows: "I am put upon a committee . . . . to prepare devices for a great seal of the confederated States. There is a gentleman here of French extraction, whose name is Du Simitiere, a painter by profession, whose designs are very ingenious, and his drawings well executed. He has been applied to for his advice. I waited on him yesterday, and saw his sketches. . . . For the seal, he proposes the arms of the several nations from whence America has been peopled, as English, Scottish, Irish, Dutch, German, etc., each in a shield. On one side of them, Liberty with her •pileus, on the other, a rifler in his uniform, with his rifle‑gun in one hand and his tomahawk on the other; this dress and these troops, with the kind of armor, being peculiar to America, unless the dress was known to the Romans. Dr. Franklin showed me yesterday a book containing an account of the dresses of all the Roman soldiers, one of which appeared exactly like it. . . . . Dr. F. Proposes a device for a seal: Moses lifting up his wand and dividing the Red Sea, and Pharaoh in his chariot overwhelmed with the waters. This motto, "Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God." Mr. Jefferson proposed the children of Israel in the wilderness, led by a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night; and on the other side, Hengist and Horsa, the Saxon chiefs from whom we claim the honor of being descended, and whose political principles and form of government we have assumed. I proposed the choice of Hercules, as engraved by Gribelin, in some editions of Lord Shaftesbury's works. The hero resting on his club; Virtue pointing to her rugged mountain on one hand, and persuading him to ascend; Sloth, glancing at her flowery paths of pleasure, wantonly p390reclining on the ground, displaying the charms both of her eloquence and person, to seduce him into vice. But this is too complicated a group for a seal or medal, and it is not original."

This letter, it will be noted, was written August 14, 1776; as the report of the committee was presented August 20, 1776, it is obvious that the recommendation must have agreed upon in a period of less than a week. It is interesting to observe that of the proposals of Adams and Jefferson, as described in this letter, not the slightest detail was employed in the report of the first committee, whereas Franklin's proposal was accepted in its entirety, including the motto he suggested, for one side of the seal. It was for the other side of the seal that E Pluribus Unum was proposed as the motto.

In the Jefferson papers in the Library of Congress is a description of the seal almost identical with that approved by the committee, and this, it is believed, is in the handwriting of Du Simitiere, mentioned in Adams' letter; the sketch accompanying it, which shows the motto E Pluribus Unum, is doubtless his work. We have, accordingly, four persons, one of whom must have suggested the phrase to the committee; these are obviously Franklin, Adams, Jefferson, and Du Simitiere.

Leaving for the time the question of the individual who may have proposed the motto, let us now take up the consideration of the various sources hitherto suggested. It has been urged (and quite frequently) that our motto comes from Virgil's Moretum (verse 103), wherein appear the words color est e pluribus unus. This passage deals with the making of a salad, and is thus translated by H. R. Fairclough:3 "Round and round passes the hand; little by little the elements lose their peculiar strength; the many colors blend into one."

The objections to believing that this is the source of our motto are: (1) the phrase is actually e pluribus unus, (2) the word color is an essential part of the sentence, (3) the idea in the Moretum is not one likely to imbed itself in the mind, (4) the Moretum is and was little read and quoted, and (5) the thought of a "salad of states" hardly seems a happy or appropriate one, or one likely p391to seem so to men who had completed the Declaration of Independence but a month and a half before.

A second theory takes us to St. Augustine. In his Confessions (IV.8) he says: "flagrare animos et ex pluribus unum facere." The idea is certainly on a loftier plane, but we have not the slightest evidence that any one of the four had the phrase in mind at that time or, indeed, at any other.

A third theory recalls the fact that the motto of the Spectator for August 20, 1711, was Exempta juvat spinis e pluribus una.4 This is a modification of Horace Epistles II.2.212, which is now read: "Quid te exempta levat spinis de pluribus una?" Conington translates it: "Where is the gain in pulling from the mind one thorn, if all the rest remain behind?" Clearly Horace and the Spectator mean "one selected from many," not "one composed of many"; moreover, the colonies would hardly appear to men like Franklin, Adams, and Jefferson, thorns to be removed. And, as in the case of the other suggestions, we have not a shred of proof that the passage in the Spectator was the source of our motto.

The suggestion of Powers in the Overland Monthly that the phrase came from a Latin poem by John Carey of Philadelphia entitled "The Pyramid of Fifteen States," is, as has been pointed out, overthrown by the very title of Carey's poem, i.e., after the addition of Vermont and Kentucky to the original thirteen.

The theory most often advanced, however, and which is, in my opinion, exceedingly well grounded, is that our motto comes directly from the legend printed on the title-page of the Gentleman's Magazine. This publication was issued in London, the printer and publisher being Edw. Cave, Jr., but employing the pseudonym "Sylvanus Urban, Gent." The first volume appeared in 1731. On the title-page of this magazine was a drawing of a hand holding a bouquet of flowers, to the left of the bouquet being the words "Prodesse et Delectare" and to the right "E Pluribus Unum." The former phrase is undoubtedly derived from Horace's Ars Poetica, verse 333: "Aut prodesse volunt aut delectare p392poetae." The other motto, E Pluribus Unum, which the Gentleman's Magazine used for over a century (save for the years 1789 to 1794) was without question taken in its turn from the Gentleman's Journal or the Monthly Miscellany, a publication issued in London from 1691 to 1694, of which the editor was Pierre Antoine Motteux, a Huguenot refugee. Motteux is of some note in the history of literature, particularly as the translator of Don Quixote.5 It has been charged that nowhere in the Gentleman's Magazine was there any acknowledgment of the fact that the bouquet and motto had been derived from the Gentleman's Journal. There is, however, a very explicit acknowledgment (tardy though it be) in the Gentleman's Magazine 3rd N. S. 1 (1856), page 9, where in the Autobiography of Sylvanus Urban (the founder) we read: "A typical device was added being a hand holding a nosegay of flowers with the motto 'E Pluribus Unum' — which device, I may inform you, was directly copied from the bouquet which Pierre Motteux had displayed, with the same motto, in his Gentleman's Journal." Motteux first used it in the number of his journal for January, 1692, and continued to employ it till the last number, November, 1694.

The sense which Motteux gave to the motto (he printed it with a comma between pluribus and unum) is indicated in his magazine for January, 1692: "That which is prefixed to this Miscellany, among other things, implies that tho' only one of the many Pieces in it were acceptable, it might gratify every reader. So I may venture to crowd in what follows, as a Cowslip and a Dazy among the Lillies and the Roses."6 Clearly then, Motteux meant "one selected from among many."

However, in the Gentleman's Magazine for 1734, the introductory poem, dealing with the motto E Pluribus Unum, shows a different meaning for the phrase. It closes thus:

"To your motto most true, for our monthly inspection,

You mix various rich sweets in one fragrant collection."

|

Here, clearly, the interpretation is "one composed of many."

p393The Gentleman's Magazine, founded forty-five years before the report of the first committee on our national seal, was undoubtedly well-known in the colonies, and the phrase on the title-page was, we may assume, likewise well-known. The question naturally arises: "How did the committee come to use a phrase of such origin and such association as a motto applied to the colonies welded into one nation?"

Of course, there are a number of phrases easily to be found in Latin literature, among them some in so well known an author as Cicero, in which appears the thought of making one out of many and, in particular, in relation to friendship. Thus in De Amicitia 21.81 we read ut efficiat paene unum e duobus, and somewhat later in the same essay (25.92) cum amicitiae vis sit in eo, ut unus quasi animus fiat ex pluribus. And in De Officiis (I.17.56)Cicero says: "Efficiturque id, quod Pythagoras vult in amicitia ut unus fiat ex pluribus."7Though these give us the meaning "one formed out of many" and deal with friendship, so closely related to a union of states, still there is not the slightest hint that any one of them was in the minds of the committee.

There is, however, in existence, a letter which, it seems to me, may have some bearing upon the restoration of the phrase in 1782. The letter is one written by Charles Thomson to William Barton, and is dated June 24, 1782, i.e., four days after Congress adopted the Great Seal with the motto E Pluribus Unum. It reads as follows: "Sir, — I am much obliged for the perusal of the elements of Heraldry which I now return. I have just dipt into it so far as to be satisfied that it may afford a fund of entertainment and may be applied by a State to useful purposes. I am much obliged for your very valuable present of Fortescue 'De Laudibus Legum Angliae,' and shall be happy to have it in my power to make a suitable return. I enclose a copy of the Device by which you have displayed your skill in heraldic science, and which meets general approbation. I am, sir, your obedient humble servant, (signed) Chas. Thomson. June 24, 1782."8

p394This letter is of very great interest; the fact that the writer and recipient were the two persons who had most to do with the Seal adopted and that the letter was written but four days after that adoption, first attract attention. Then one notes that the last sentence deals very directly with the seal; the first and second sentences relating to the elements of heraldry are likewise seen to be connected with it, especially in view of the reference to heraldic science in the last sentence. That leaves the third sentence as having apparently nothing to do with the seal and breaking the connection of thought between the two opening sentences and the last sentence. Anything is possible in letter-writing, but somehow such an arrangement in a letter of four sentences, written at the very time when the preparation of the seal was uppermost in the mindis of both, rouses one's curiosity, to say the least.

Accordingly, I turned to Fortescue's work and quickly found in chapter XIII the following: "Quo, primo Polit. dicit Philosophus 'Quod quandocunque ex pluribus constituitur unum inter illa, unum erit Regens, et alia erunt recta'." This is translated: "Wherefore, the philosopher, in the first of his politics, says 'Whensoever a multitude is formed into one body or society, one part must govern, and the rest be governed'." Here we find the words ex pluribus constituitur unum, meaning "one formed out of many," dealing with government, and found in so respectable an author as Fortescue. This may of course be a mere coincidence, but if so, it is an exceedingly strange one.

It seems to me that the restoration of E Pluribus Unum at the very time Fortescue was passing from Barton to Thomson may well have received some impetus from this phrase quoted by Fortescue from "the philosopher." By "the philosopher" (as is made clear by the beginning of chapter VIII) Fortescue means Aristotle. And turning to the latter's Politics (I.5.3) we readily find the passage employed by Fortescue, which is translated by W. E. Bolland as follows: "For whenever there is a combination of several parts, and one common result arising from it, whether those parts be continuous or distinct, there is in all cases apparent the element which rules and that which is ruled." Fortescue's p395phrase, therefore, goes back to ἐκ πλειόνων . . . ἔν of Aristotle. And in Thomson's restoration of E Pluribus Unum this quotation seems to me in all likelihood to have had some weight.

But after all Thomson merely restored what the first committee proposed, and while it is of interest to learn that Fortescue's use of a phrase from Aristotle played some part in that restoration, yet the proposal itself was made in the period between August 14 and August 20, 1776, and to that time and the original committee we shall accordingly return.

The honor of proposing the phrase must, as we have seen, be given to one of these four — Du Simitiere, Adams, Jefferson, or Franklin. It is indeed true that the sketch of the obverse of the seal found in the Jefferson papers not only is undoubtedly the work of Du Simitiere but also is identical with the seal recommended by the first committee with the substitution in the latter of the figure of Justice for Du Simitiere's "rifler." And in this sketch we find the motto E Pluribus Unum. From this fact it has been strongly urged that it was Du Simitiere who proposed the motto.

The question at once arises: "Is this the sketch which Adams described in his letter of August 14, 1776?" If so, it would seem exceedingly strange that he did not mention this motto in his letter written the day after seeing it, though in that very letter he cites the motto Franklin had proposed. Moreover, in Du Simitiere's sketch also appears "the Eye of Providence," to which Adams makes no reference in his letter. In passing, it is of interest to note that the only portions of the report of the first committee which became part of our national seal are the motto E Pluribus Unum and the eye of Providence, the only features of importance in that report whose originator is not definitely stated.

As one looks at Du Simitiere's sketch,9 he finds it impossible to believe that Adams would not have referred to these two features, had the sketch been the one he saw the day before. One is far more inclined to believe that after meeting Adams and the other members of the committee (i.e., after August 14), Du p396Simitiere drew the sketch referred to, adding the motto either on his own volition or on the suggestion of another.

Obviously, the fact that the motto appears on Du Simitiere's sketch does not prove that the person who drew the sketch, proposed the motto. In the first place, the omission of any mention of the motto or the eye of Providence from

Adams' account, seems to me to make it very unlikely that this was the sketch that he had seen on August 13. If it was not, and if it was drawn between August 14 and August 20, it is at least equally probable that Du Simitiere added to his sketch the motto another had proposed. In the second place, we have an interesting sidelight in reference to the design which Du Simitiere pound for the seal of Virginia, apparently also in August, 1776. Two possible mottoes were proposed for it, the sketch reading: "Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God; or Rex est qui regem non habet (suggested by Mr. Jefferson)."10 It is here definitely stated that the motto was suggested to Du Simitiere by another; the first motto, it will be noted, is, moreover, the one which Franklin proposed that very month as the motto for the seal of the United States.

Adams' account, seems to me to make it very unlikely that this was the sketch that he had seen on August 13. If it was not, and if it was drawn between August 14 and August 20, it is at least equally probable that Du Simitiere added to his sketch the motto another had proposed. In the second place, we have an interesting sidelight in reference to the design which Du Simitiere pound for the seal of Virginia, apparently also in August, 1776. Two possible mottoes were proposed for it, the sketch reading: "Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God; or Rex est qui regem non habet (suggested by Mr. Jefferson)."10 It is here definitely stated that the motto was suggested to Du Simitiere by another; the first motto, it will be noted, is, moreover, the one which Franklin proposed that very month as the motto for the seal of the United States.

After all, it seems less likely that Du Simitiere, a foreigner and "a painter by profession," should have taken upon himself the responsibility of proposing a motto for the seal of the United States than that, as in case he should have incorporated in his sketch the suggestion of another. We must then turn to the three members of the committee.

John Adams taught school and studied law in Worcester from 1756 to 1758 and, interestingly enough, in a list of works dealing with the law that he read at that time, he names Fortescue.11 However, that was twenty years before the date of the report of the committee on the seal, and apparently Fortescue made no greater impression on him than the other books in the list. But it is important to observe that the notion of the need of a union among the colonies was already a firm conviction on his part. He wrote on October 12, 1755: "The only way to keep us from setting up for ourselves is to disunite us. Divide et impera."12

p397Jefferson has been mentioned as the person who proposed the motto. There is, however, not a shred of proof in any account that has come to my notice. It is clear that he was very much interested in mottoes. We have already seen that he suggested a motto for Virginia. In a letter to John Page (1776)13 he discusses another motto proposed for that state. He says: "But for God's sake what is the 'Deus nobis haec otia fecit!" It puzzles everybody here. If my country really enjoys that otium it is singular, as every other colony seems to be hard struggling. . . . This device is too enigmatical. Since it puzzles now, it will be absolutely insoluble fifty years hence."14

Not only did mottoes interest him, but he, too, had again and again stressed the idea of unity. Thus he said: "The States should be one as to everything connected with foreign relations, and several as to everything purely domestic."15

There is, moreover, an incident which shows: (1) that Jefferson's mind had for some time been busy with the matter of a seal and, in particular, with a motto for it, and (2) that the idea of a union as a source of strength had been its main feature. For in 1774 he made this note in his almanac: "A proper device (instead of arms) for the American states would be the Father presenting the bundle of rods to his sons. The motto 'Insuperabiles si inseparabiles' an answer given in parl[iament] to the H[ouse] of Lds, and commons."16 The reference is to the fable, found in Aesop, of the father who makes clear to his sons their individual weakness and their collective strength by showing them how easily single rods can be broken, while the utmost strength cannot break them if bound together.b But nothing direct has thus far been brought forward connecting Jefferson with our national motto.

Let us now turn to the third member of the committee, Benjamin Franklin. It was he, it will be recalled, who proposed the design and the motto accepted by the committee for the other side of the seal; it will also be recalled that the designs which we p398know for certain were proposed by Adams and Jefferson were entirely rejected.

It does not, to be sure, demand a knowledge of Latin for one to suggest a Latin motto; it is, however, of interest to ascertain whether Franklin had any knowledge of the language. In his Autobiography17 he says: "I have already mentioned that I had only one year's instruction in a Latin school, and that when very young, after which I neglected that language entirely. But, when I had attained an acquaintance with the French, Italian, and Spanish, I was surpriz'd to find on looking over a Latin Testament, that I understood so much more of that language than I had imagined, which encouraged me to apply myself again to the study of it, and I met with more success, as those preceding languages had greatly smooth'd my way."

Latin phrases and quotations occur not infrequently in Franklin's writings, particularly in the earlier ones; among the authors cited one notes Cicero, Terence, Sallust, Seneca, Livy, Persius, Horace, and Virgil. On the use of such quotations we have an interesting expression on Franklin's part in the editorial preface to the New England Courant no. 80, 1723:18 "Gentle Readers, we design never to let a Paper pass without a Latin Motto if we can possibly pick one up, which carries a Charm in it to the Vulgar, and the learned admire the pleasure of Construing. We should have obliged the World with a Greek scrap or two, but the Printer has no Types, and therefore we intreat the candid Reader not to impute the defect to our Ignorance, for our Doctor can say all the Greek Letters by heart."

That Franklin had paid attention to mottoes embodying the idea of union, is made evident by an article in the Pennsylvania Gazette for May 9, 1754; at the end of the article is a wood‑cut, in which is the figure of a snake, separated into parts, to each of which is affixed the initial of one of the colonies, and at the bottom in large capital letters the motto "Join or Die."19

![[image ALT: A schematic drawing of a snake cut into segments, labeled from the head at the right to the tail at the left: N. E., N. Y., N. J., P., M., V., N. C., S. C. It is a political cartoon by Benjamin Franklin.]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Gazetteer/People/Benjamin_Franklin/Join_or_Die*.jpg) |

p399Granted that Franklin had some knowledge of Latin, that he used Latin quotations, and that the idea of a union of the colonies had for a number of years been present in his mind; the important question still remains: Did Franklin have an intimate knowledge of the Gentleman's Magazine and, consequently, of the motto on its title page?

In the first place, articles of his frequently appeared in it. With no attempt to give a complete list of his contributions the following may be cited as illustrations:

Letter to Sir Hans Sloane on Asbestos, dated June 2, 1725: G. M., September, 1780.

Letter on the Electrical Kite read at the Royal Society, December 21,

1752: G. M., 1752.

1752: G. M., 1752.

An Act for the better ordering and regulating such as are willing and desirous to be united for military purposes within the province of Pennsylvania: G. M., February, 1756.

Dialogue between X, Y, and Z, concerning the present state of affairs in Pennsylvania: G. M., March, 1756

An Edict by the King of Prussia, Dantzic, September 5, (1773): G. M., October, 1773.

Rules by which a great empire may be reduced to a small one: G. M., September, 1773.

In the second place, Franklin refers often to both the Gentleman's Magazine and Cave, its publisher. In his Autobiography20 he writes: "Mr. Collinson then gave them (i.e., the papers on electricity) to Cave for publication in his Gentleman's Magazine, but he chose to print them separately in a pamphlet, and Dr. Fothergill wrote the preface. Cave, it seems, judged rightly for his profit, for by the additions that arrived afterward, they swell'd, to a quarto volume, which has had five editions, and cost him nothing for copy-money." In a letter of September 14, 1752,21 we read: "I see by Cave's Magazine for May, that they have translated my electrical papers into French and printed p400them in Paris."22 His connection continued until his last years, for we find a letter of his dated October 20, 1789, addressed to Sylvanus Urban, Esq. (the pseudonym of the author) and beginning: "In your valuable magazine for July, 1788, I find a review of Dr. Kippis' 'Life of Cook'23 . . . ." His continuous attention to it is shown by another letter of 1789,24 in which he says: "Whoever compares a volume of the Gentleman's Magazine, printed between the years 1731 and 1740, with one of those printed in the last ten years, will be convinced of the much greater Degree of Perspicuity given by black Ink than by Grey."

On the other hand, the interest in Dr. Franklin on the part of the editor of the Gentleman's Magazine25 and his high respect for Franklin are attested in the number for July, 1767. In it appears the "Examination of Dr. Franklin in the British House of Commons respecting the Stamp Act," and concerning it the editor says: "The questions in general are put with great subtilty and judgment, and they are answered with such deep and familiar knowledge of the subject, such precision and perspicuity, such temper and yet such spirit, as do the greatest honor to Dr. Franklin and justify the general opinion of his character and abilities."

Another compliment is paid to him in the poem introductory to volume 23 of the Magazine (1753), which reads in part as follows:

"The maid (i.e., America) new paths in science tries,

New gifts her daring toil supplies;

She gordian knot of art unbinds;

The Thunder's secret source she finds;

With rival pow'r her light'nings fly,

Her skill disarms the frowning sky;

For this the minted gold she claims,

Ordain'd the meed of gen'rous aims."

|

p401And that no one should fail to understand these lines, the following footnote appears: "Benjamin Franklyn,º Esq; of Philadelphia, in America, obtained the Royal Society's medal for his amazing discoveries in electricity, an account of which first came into our hands."

That Franklin was well acquainted with the magazine, and that his writings and his name appeared often in its pages is, I think, sufficiently clear. Indeed, Franklin's correspondence makes it evident that negotiations were under way for him to serve as its agent in America. In a letter to William Strahan, dated Philadelphia, November 27, 1755,26 he writes: "I shall be glad to be of any service to you in the affair you mention relating to the Gentleman's Magazine, and our daughter (who already trades a little in London) is willing to undertake the distributing of them per post from this place, hoping it may produce some profit to herself. I will immediately cause advertisements to be printed in the papers here, at New York, New Haven, and Boston, recommending that magazine and proposing to supply all who will subscribe for them at 13s. this currency, a year, the subscribers paying down the money for one year beforehand; for otherwise there will be considerable loss by bad debts. As soon as I find out what the subscription will produce I shall know what number to send for. Most of those for New England must be sent to Boston. Those for New York, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Maryland must be sent to New York or Philadelphia, as opportunities offer to one place or the other. As to Virginia, I believe it will scarce be worth while to propose it there, the gentlemen being generally furnished with them by their correspondents in London. Those who incline to continue, must pay for the second year three months before the first expires, and so on from time to time. The postmaster in those places to take in the subscription money and distribute the magazines, etc. These are my first thoughts. I shall write further. That magazine has always been, in my opinion, by far the best. I think it never wants matter, both entertaining and instructive, or I might now and then furnish you p402with some little pieces from this part of the world." Again in a letter of July 2, 1756,27 Franklin discusses with Strahan his "scheme of circulating your magazine"; it is thought, however, that the plan was not carried out.

There is a final and most important tie. Benjamin Mecom, Franklin's nephew, began on August 31, 1758, the publication of The New England Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure; it lived but a few months. But two copies are said to be in existence,28 one being a copy of the first number; in both of these we find on the title-page the familiar bouquet of the Gentleman's Magazine, and both of the mottoes which had appeared with it, Prodesse & Delectare, and E Pluribus Unum. Below them (in the October number) appears the couplet:

Alluring Profit with Delight we blend;

One, out of many, to the Public send.

|

Not only did the bouquet and the two mottoes come from the Gentleman's Magazine but Mecom also used the name of Urbanus Filter, clearly derived from Sylvanus Urban of the English magazine.

We see, accordingly, that Franklin wrote frequently for the Gentleman's Magazine, referred often to it in his letters, and was often, referred to in its pages and in most complimentary manner. He thought very highly of it; he said "(it) has always been, in my opinion, by far the best." In fact negotiations were entered on to have him act as its American agent. His nephew in Pittsburg the New England Magazine shows his indebtedness to the Gentleman's Magazine in a number of ways, one of which is the use of E Pluribus Unum as a motto on the title-page.

Is it not, then, natural to infer that Franklin proposed this motto, which was used on the title-page of every issue of a magazine which he knew and esteemed so highly?

But it may be asked: "Does it seem probable that Franklin would have proposed for the national motto a scrap of a phrase found on the title-page of a magazine along with Prodesse et Delectare and a bouquet of flowers, a phrase having no noble p403associations, and, in particular, identified with an English publication?"

As to the first of these, Franklin would not, I believe, have had any scruples. If the phrase met his needs, he would use it. The motto which we are certain he proposed for the seal ("Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God") is to be found in an article entitled "Bradshaw's Epitaph," published in the Pennsylvania Evening Post on December 14, 1775. The article is anonymous, but it is agreed that it is Franklin's. In the article it is stated that this phrase was part of the epitaph of John Bradshaw, one of the judges who sentenced Charles I. This it certainly was not, but, instead, indubitably the creation of Benjamin Franklin himself.29 If, then, it is clear that Franklin proposed a line of such a history for the nation's motto, it hardly seems likely that he would have hesitated to use a phrase that satisfied him, merely because it appeared on the title-page of a magazine.

But, it may be urged, that the magazine was English would surely have made it unwelcome to the Americans. Possibly it would have done so under ordinary conditions. There is, however, a poem which introduces volume 45 (1775) and which, therefore, must have been written at the end of that year, that, I believe must have so kindled the hopes and

fired the ardor of the Americans that the motto of the magazine containing it would not only have been tolerated but even welcomed. The poem, we must remember, could not have reached the American colonies before the early part of 1776. It is "Addressed to Mr. Urban on completing the XLVth Volume of the Gentleman's Magazine:

fired the ardor of the Americans that the motto of the magazine containing it would not only have been tolerated but even welcomed. The poem, we must remember, could not have reached the American colonies before the early part of 1776. It is "Addressed to Mr. Urban on completing the XLVth Volume of the Gentleman's Magazine:

Close, Urban, close th' historic page

Disgraced with more than civil rage;

And may our annals never tell

To that dire rage what victims fell!

Let dark oblivion hide the plain

O'erspread with heaps of Britons slain;

Friends, brothers, parents, in the blood

Of brothers, friends, and sons imbrued!

*****

p404Griev'd at the past, yet more we fear

The horrors of the coming year.

Ships sunk or plunder'd, slaughter'd hosts,

Towns burnt, and desolated coasts.

Yet, sever'd by th' Atlantic main,

Though great, our efforts must be vain;

Resources so remote must fail,

Nor skill nor valor can prevail:

When winds, waves, elements are foes,

In vain all human means oppose.

At length, when all these contests cease,

And Britain weary'd rests in peace,

Our sons, beneath yon Western skies

Shall see one vast republic rise;

Another Athens, Sparta, Rome

Shall there unbounded sway assume;

Thither her ball shall Empire roll,

And Europe's pamper'd states controul,

Though Xerxes rul'd and lash'd the sea,

The Greeks of old thus would be free;

Nor could the power and wealth of Spain

Th' United Netherlands regain.

|

Think what such a glowing prophecy must have meant to the struggling colonies. Hesitation to accept a motto because it stood on the title-page of the magazine which had published this tribute and exhortation, would surely have been far from their minds.

And so our motto, selected between August 14 and August 20, 1776, was unquestionably taken from the title-page of the Gentleman's Magazine. And the evidence is overwhelming that the suggestion came from Benjamin Franklin, who was so closely bound to the Magazine by numerous ties. And the poem which was introductory to the volume of 1775 must have given added strength to such a proposal and cleared away any doubts as to the propriety of its selection.

From the Gentleman's Magazine we trace E Pluribus Unum back to the second volume of the Gentleman's Journal, a magazine published in London from 1691 to 1694 by Motteux, the Huguenot p405refugee. Its first known appearance is accordingly on the title-page of the Journal for 1692. Whether Motteux found it in some work or composed it himself, we can but surmise. The only evidence upon this question is in Motteux' own words. On page 19 of the number of the Gentleman's Journal for January, 1692, he discusses "devices" and the mottoes used with them; after some mention of those of various academies he continues:30

"Which Devises (by the way) are a kind of Poetry which we do not derive from the Ancients, for the Hieroglyphics of the Egyptians were at best only half or imperfect Devises, and Bodies without Souls; whereas regular Devises sometimes express more in one word, than doth a volume. But there is a great deal of Wit requir'd to find out Subjects proper for the Body of a Devise, and Words or a Soul suitable to it. But of these I hope to treat in some of my next.

"That which is prefix'd to this Miscellany, among other things, implies that tho' only one of the many Pieces in it were acceptable, it might gratify every Reader. So I may venture to crowd in what follows, as a Cowslip and a Dazy among the Lillies and the Roses."

"That which is prefix'd to this Miscellany, among other things, implies that tho' only one of the many Pieces in it were acceptable, it might gratify every Reader. So I may venture to crowd in what follows, as a Cowslip and a Dazy among the Lillies and the Roses."

While there is of course nothing explicit in all this, still the impression it leaves is that Motteux himself composed the motto or adapted it. And of all the phrases resembling our national motto that have been found in classical authors, that in Horace's Epistles II.2.212 seems to me by far the most likely to have been the one modified by Motteux. It will be recalled that all our editions read: "Quid te exempta levat spinis de pluribus una?" But, as we have already seen, it is to be found in the Spectator for August 20, 1711, in the form e pluribus una, a very simple and natural modification. The phrase e pluribus una is almost as near our motto as that in the Moretum; we must, moreover, recall that Motteux clearly meant "one selected from among many," which is the meaning of the Horatian passage, but not of that in the Moretum. Horace was read and quoted with the utmost frequency, and, as we have noted, this very verse was the p406motto for one of the numbers of the Spectator. And, interestingly enough, the words Prodesse et Delectare added as a second motto in the Gentleman's Magazine to accept E Pluribus Unum were unquestionably drawn from Horace's Ars Poetica, the poem immediately following the second book of his Epistles. It seems to me, therefore, not unlikely that E Pluribus Unum is Motteux' adaptation of e (or de) pluribus una, Horace, Epistle II2.212.

In short, our national motto is undoubtedly drawn from the phrase used on the title-page of the Gentleman's Magazine which in its turn obtained it from the Gentleman's Journal (1692‑1694). There our knowledge ceases, but it may easily be that Motteux, the editor of the Gentleman's Journal, adapted it from Horace, Epistle II.2.212. And so a Frenchman adapted and published on the title-page of a magazine issued in England a group of three Latin words which became the national motto of this composite people, the United States of America.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Charles Francis. Familiar Letters of John Adams and his Wife Abigail Adams, during the Revolution (pp210‑211). New York; Hurd and Houghton, 1876.

Arnold, Howard Payson. Historic Side-lights (especially pp279‑315 and pp63‑66); (by far the best and most complete discussion of the subject; many of his conclusions are accepted in this article.)

Champlin, J. D. Jr. The Great Seal of the United States [in Galaxy 23:691‑4].

Chautauquan 31:321‑2 (1900); based entirely on Arnold's Historic Side-lights).

Fortescue. De Laudibus Legum Angliae (The Translation into English published A.D. MDCCLXXV and the original Latin Text with Notes) by A. Amos (Cambridge, 1825), pp220‑221 and 37.

The Gentleman's Magazine or Monthly Intelligencer, London. 1731 and following volumes.

Green, Samuel A. Origin of E Pluribus Unum [in American Journal of Numismatics, V (1870), 27].

p407Green Bag 14:440; (an article quoted from the Boston Herald).

Historical Magazine III, April, 1859, p121 and August, 1859, p255.

Hunt, Gaillard. The History of the Seal of the United States. Washington, D. C.; Department of State, 1909 (a work of great value).

Lander, E. T. The Great Seal of the United States [in Magazine of American History 29 (1893), 471].

Lippincott's Magazine, February, 1868. (A mere reference to the Moretum.)

Lloyd, J. W. "The Great Seal of the United States" [in St. Nicholas 33:790‑1 (1906)] (a popular account).

Lossing, B. J. In Harper's Magazine XIII (July, 1856), 178‑186.

Magazine of American History 2.2 (1878), p636.

Massachusetts Historical Society, Proceedings, 1873‑75, p39; 1866‑7, p351.

Modern Language Association Publications 32 (1917), 22‑58.

Powers, Stephen. Picking Historical Marrow-bones [in Overland Monthly, VI.271‑9 (March, 1871)].

Preble, George Henry. History of the American Flag (pp683‑696). (Second revised edition, Boston, 1880.)

Smyth, Albert Henry. The Writings of Benjamin Franklin. Macmillan & Co.; 10 volumes.

Totten, Charles A. L. The Seal of History. New Haven, 1897; 2 volumes.

Totten, Charles A. L. The Seal of History. New Haven, 1897; 2 volumes.

Zieber, Eugene. Heraldry in America (pp94‑103). Philadelphia, 1909. (Based wholly upon the account by Gaillard Hunt.)

The Author's Notes:

1 This report is on file in the archives of the Department of State in Washington, and is endorsed: "No. 1. Copy of a Report made August 10, 1776." It will be noted that the date is incorrect and should be August 20.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

2 Charles Francis Adams, Familiar Letters of John Adams and his Wife, Abigail Adams, during the Revolution (New York, 1876), p210.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

3 Vergil, vol. II, in the Loeb Classical Library.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

4 This is the reading in "The Spectator," volume second, London, MDCCLIV.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

5 On Motteux see the Cambridge History of English Literature, IX.256, 263, 270‑2.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

6 Arnold, Historic Side-lights, 291‑2.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

7 Cf. also Hieron. ep. 83: "quasi unus in pluribus es, ut sis unus ex pluribus." — The reverse of our phrase is to be found in Cic. De Natura Deorum II.127: "ut ex uno plura generentur."

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

8 Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1866‑7, pp351‑2.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

9 Arnold, Historic Side-lights, opposite page 282.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

10 Burk, History of Virginia, vol. IV, appendix 14.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

11 Charles Francis Adams, The Works of John Adams, I, 46.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

12 Ibid., I, 23.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

13 P. L. Ford, Writings of Jefferson (1892), II, 70.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

14 See also ibid., II, 70.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

15 Arnold, Historic Side-lights, 267.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

16 P. L. Ford, Writings of Jefferson (1892), I, 420.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

17 Albert Henry Smyth, The Writings of Benjamin Franklin, I, 347.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

18 Ibid., II, 52.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

19 Jared Sparks, The Works of Benjamin Franklin (1890), III, 25. The cut is reproduced on page 418 of The Many-sided Franklin by Paul Leicester Ford, 1899.

Thayer's Note: . . . and is not given in the original print article. I have added the (public-domain) illustration from an online source.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

20 Smyth, I, 418.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

21 Ibid., III, 97‑8.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

23 Ibid., X, 43.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

24 Ibid., X, 80.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

25 The Gentleman's Magazine contains many references to Franklin, the index listing forty-nine appearances of his name. The most interesting is probably that in LX.571, where there is a long account of his life together with numerous references to earlier volumes of the Magazine.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

26 Smyth, III, 303.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

27 Ibid., III, 337‑8.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

28 Arnold, Historic Side-lights, 63.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

29 Ibid., 238 foll.; Hunt, The History of the Seal of the United States, 14‑16.

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

30 Arnold, Historic Side-lights, 288, and reproduction of page 19 of the Gentleman's Journal.

Thayer's Notes:

![[decorative delimiter]](http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/Images/Utility/Symbols/WP.gif)

b As with most of "Aesop", the fable exists in several versions under the names of a constellation of ancient authors both Greek and Latin, which in turn have been variously numbered by their modern editors. An English translation is provided at Elfinspell, under Babrius, XLVII.

No comments:

Post a Comment