New York Review of Books

‘Fuck’-ing Around

What the F: What Swearing Reveals About Our Language, Our Brains, and Ourselves

by Benjamin K. Bergen

Basic Books, 271 pp., $27.99

In Praise of Profanity

by Michael Adams

Oxford University Press, 253 pp., $17.95

Obscene language presents problems, the linguist Michael Adams writes in his new book, In Praise of Profanity, “but no one seems to spend much time thinking about the good it does.” Actually, a lot of people in the last few decades have been considering its benefits, together with its history, its neuroanatomy, and above all its fantastically large and colorful word list. Jesse Sheidlower’s The F-Word, an OED-style treatment of fuck that was first published in 1995, has gone into its third edition, ringing ever more changes—artfuck, bearfuck, fuck the deck, fuckbag, fuckwad, horsefuck, sportfuck, Dutch fuck, unfuck—on that venerable theme.

Meanwhile, Jonathon Green’s Green’s Dictionary of Slang, in three volumes (2010), lists 1,740 words for sexual intercourse, 1,351 for penis, 1,180 for vagina, 634 for anus or buttocks, and 540 for defecation and urination. In the last few months alone there have been two new books: What the F, by Benjamin Bergen, a cognitive scientist at the University of California at San Diego, together with Adams’s In Praise of Profanity. So somebody is interested in profanity.

Many writers point out that there hasn’t been enough research on the subject. As long as we haven’t cured cancer, it’s hard to get grants to study dirty words. Accordingly, there don’t seem to have been a lot of recent discoveries in this field. Very many of Bergen’s and Adams’s points, as they acknowledge, have been made in earlier books, an especially rich source being Melissa Mohr’s Holy Shit: A Brief History of Swearing (2013). Mohr even reads us the graffiti from the brothel in ancient Pompeii—disappointingly laconic (e.g., “I came here and fucked, then went home”), but good to know all the same.

Of course one wants to know the history of the words, and all the books provide it, insofar as they can. Fuck did not get its start as an acronym, as has sometimes been jocosely proposed (“For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge,” etc.). If it had, there wouldn’t be so many obvious cognates in neighboring languages. Sheidlower lists, among others, the German ficken (to copulate), the Norwegian regional fukka (ditto), and the Middle Dutch fokken (to thrust, to beget children), all of them apparently descendants of a Germanic root meaning “to move back and forth.” Sheidlower says fuck probably entered English in the fifteenth century, but Bergen, writing later, reports that the medievalist Paul Booth recently came across a legal document from 1310 identifying a man as Roger Fuckebythenavel. Booth conjectures that this might have been a metaphor for something like “dimwit.” On the other hand, it could have been a nickname inflicted on an inexperienced young man who actually tried to do it that way, and whose partner could not resist telling her girlfriends.

Something to note here is that the word appeared in a legal document. For a long time fuck was not considered especially vile. Cunt, too, was once an ordinary word. A fourteenth-century surgery textbook calmly states that “in women the neck of the bladder is short and is made fast to the cunt.” Until well after the Renaissance, the words that truly shocked people had to do not with sexual or excretory functions but with religion—words that took the Lord’s name in vain. As late as 1866, Baudelaire, who had been rendered aphasic by a stroke, was expelled from a hospital for compulsively repeating the phrase cré nom, short for sacré nom (holy name).

Many exclamations that now seem to us merely quaint were once “minced oaths.” Criminy, crikey, cripes, gee, jeez, bejesus, geez Louise, gee willikers, jiminy, and jeepers creepers are all to Christ and Jesus what frigging is to fucking. The shock-shift from religion to sexual and bathroom matters was of course due primarily to the decline of religion, but Mohr points out that once domestic arrangements were changed so as to give people some privacy for sex and elimination, references to these matters became violations of privacy, and hence shocking.

Though research has not done much for profanity, the opposite is not true. Neurologists have learned a great deal about the brain from studying how brain-damaged people use swearwords—notably, that they do use them, heavily, even when they have lost all other speech. What this suggests is that profanity is encoded in the brain separately from most other language. While neutral words are processed in the cerebral cortex, the late-developing region that separates us from other animals, profanity seems to originate in the more primitive limbic system, which lies embedded below the cortex and controls emotions. As a result, we care about swearwords differently. Hearing them, people may sweat (this can be measured by a polygraph), and, tellingly, bilingual people sweat more when the taboo word is in their first language.

The very sound of obscenities—forget their sense—seems to ring a bell in us, as is clear from the fact that many of them sound alike. In English, at least, one third of the so-called four-letter words are indeed made up of four letters, forming one syllable, and in nine out of ten cases, Bergen writes, the syllable is “closed”—that is, it ends in a consonant or two consonants. Why? Probably because consonants sound sharper, more absolute, than vowels. (Compare piss with pee, cunt with pussy.) It may be this tough-talk quality that accounts for certain widely recognized benefits of swearwords. For example, they help us endure pain. In one widely cited experiment, subjects were instructed to plunge a hand into ice-cold water and keep it there as long as they could. Half were told that they could utter a swearword while doing this, if they wanted to; the other half were told to say some harmless word, such as wood. The swearing subjects were able to keep their hands in the water significantly longer than the pure-mouthed group.

Related to this analgesic function is swearing’s well-known cathartic power. When you drop your grocery bag into a puddle or close the window on your finger, geez Louise is not going to help you much. Fuck is what you need, the more so, Adams says, because it doesn’t just express an emotion; it states a philosophical truth. By its very extremeness, it is saying that “one has found the end of language and can go no further. Profanity is no parochial gesture, then. It strikes a complaint against the human condition.” And in allowing us to do so verbally, it prevents more serious damage. “Take away swearwords,” writes Melissa Mohr, “and we are left with fists and guns.” The same is no doubt true of obscene gestures. According to Bergen, people have been giving each other the finger for over two thousand years, and that must certainly be due in part to its usefulness in forestalling stronger action.

But even when anger is not involved, obscenity seems to operate on the side of fellowship. The philosopher Noel Carroll told me once of an international conference in Hanoi in 2006. On the first day, to break the ice, the Vietnamese and the Western scholars, taking turns, had a joke-telling contest. The first two Vietnamese scholars told off-color jokes, but the Westerners, still fearful of committing some social error, stuck to clean jokes. A stiff courtesy reigned. Finally, the third Western contestant (Carroll, and he recounted this proudly) told a filthy joke about a rooster, and everyone relaxed. The conference went on to be a great success.

This barrier-crossing function, together with other forces—boredom, machismo, the analgesic effect—helps to account for the notorious frequency of fuck and, perhaps more frequently, of motherfucker in speech exchanged by people in the military and by men in work crews, jazz groups, and similar situations. Adams proposes that the reason dirty words foster human relations is that they depend on trust, our trust that the person we are talking to shares our values and therefore won’t dislike us for using a taboo word. “If a relationship passes the profanity test,” he writes, “the parties conclude a pact that whatever they say in their intimate relationship stays in their intimate relationship.” I would say, indeed, that they make a pact that they have an intimate relationship. (This is the place to add that many people find that “talking dirty” enhances sex.) But such considerations seem too tender to apply to the ubiquity of fuck and motherfucker among soldiers and workmen, to whose interchanges these words seem, rather, to apply a sort of hard, even glaze, a compound of irritation and stoicism, together with, yes, a sense of subjection to a common fate.

But situations vary. According to the largest surveys that Bergen could lay his hands on, the English, the Americans, and the New Zealanders all agree that of sexually related profanities, cunt is the dirtiest. Yet there is huge disagreement within these countries about how foul a word is. (About one third of New Zealanders thought cunt would be acceptable for use on television.) There is great variation in the investment that different societies have in religious profanity, and in some, the taboo on blasphemy has survived considerable secularization. In Quebec, Bergen says, tabarnack (tabernacle) and calisse (chalice) are far stronger obscenities than merde (shit) and foutre (fuck). Germany has a sort of specialty in scatological obscenities: Arschloch (asshole), Arschgesicht (ass face), Arschgeburt (born from an asshole), et cetera.

Japan, curiously, does not have swearwords in the usual sense. You can insult a Japanese person by telling him that he has made a mistake or done something foolish, but the Japanese language does not have any of those blunt-instrument epithets—no ass face, no fuckwad—that can take care of the job in a word or two. The Japanese baseball star Ichiro Suzuki told The Wall Street Journal that one of the things he liked best about playing ball in the United States was swearing, which he learned to do in English and Spanish. “Western languages,” he reported happily, “allow me to say things that I otherwise can’t.”

The West is moving toward further liberalization, a trend hastened by cable TV and the Internet. Melissa Mohr reports that in March 2011, three of the top-ten hit songs on the Billboard pop music chart had titles containing obscenities. Nevertheless, the Federal Communications Commission still imposes fines on broadcasters who use what it regards as profanity. Steven Pinker, in his The Stuff of Thought (2007), reprints the excellent “FCC Song,” by Eric Idle, of Monty Python:

Fuck you very much, the FCC.

Fuck you very much for fining me.

Five thousand bucks a fuck,

So I’m really out of luck.

That’s more than Heidi Fleiss was charging me.

But though the FCC levies fines, it has never published a list of the words that in its view merit this penalty, nor does the ratings board of the Motion Picture Association of America specify what material leads to what ratings. Bergen records that when Matt Stone and Trey Parker submitted their South Park feature to the MPAA board, it came back with an NC-17 rating, one level below R. (No one under the age of seventeen, even if accompanied by an adult, may be admitted to a film rated NC-17.) In the filmmakers’ view, this would have sunk the film financially. At the same time, they resented the meddling, so, while they changed passages that the board singled out as problematic, they took advantage of its failure to explain exactly what the problem was. Stone told the Los Angeles Times, “If there was something they said couldn’t stay in the movie, we’d make it 10 times worse and five times as long. And they’d come back and say, ‘OK, that’s better.’”

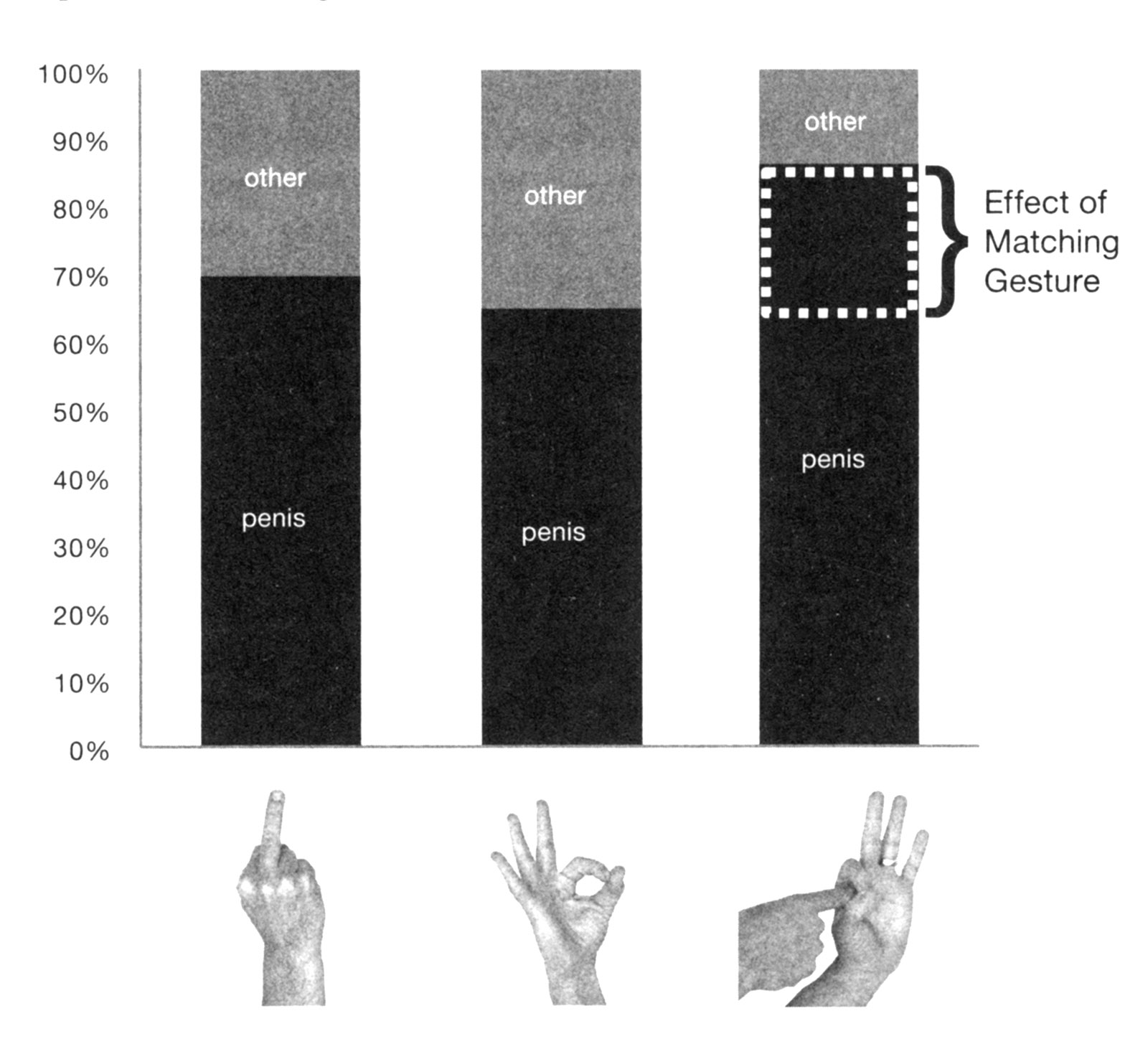

The act of writing a sober book, with charts and notes and bibliography, about dirty words is itself a species of comedy, and Bergen and Adams use this for all it’s worth. While actually doing a serious job—Bergen offers useful information, and Adams supplies subtle, nuanced reflections (he is the most philosophical of the writers I have read on obscenity)—they are also, unmistakably, having a good time, and trying to give us one. Bergen publishes scholarly graphics full of filthy gestures, and, on the stated assumption that we need to know how American Sign Language lines up with spoken English, he reproduces photos of an attractive woman signing “You bitch you” and worse.

Adams, in a long digression, pays tribute to a book on latrine-wall graffiti by the linguist Allen Walker Read. Ostensibly, he is trying to rescue Read’s findings from oblivion (the book was privately printed in Paris in 1935 and is now more or less unobtainable), but the quotations, like Bergen’s dirty pictures in ASL, are suspiciously numerous and entertaining. In an auto camp in Truckee, California, Read found the following:

Shit here shit clear

Wipe your ass

And disappear

Shakespear

Adams himself has made a long study of the walls of public bathrooms and adds his findings to Read’s. The traditional offerings, he says, are reflections on the meaning of life, contact information for people who would like to make friends, specifications of the length and girth of one’s penis (“My dick is so long it can turn corners”), teacher evaluations (“Mr. Radley is a cocksucker”), and art, of course, together with art criticism (“The man that drew this never saw a cunt”). The discussion goes on for twenty-five pages, all of them rewarding.

But while the subject of these books sends the writers off on enjoyable tangents, it also encourages some tediousness. Adams cannot avoid the temptation to set up straw men—for example, a book, The No Cussing Club: How I Fought Against Peer Pressure and How You Can Too!, brought out in 2009 by a fourteen-year-old boy, McKay Hatch. Hatch, disgusted by the amount of obscenity he heard in his school, founded this clean-speaking organization. According to publicity materials, the No Cussing Club now has 20,000 members. “I was just a regular kid,” Hatch writes. “Except, now, my dad, my teachers, even the mayor of my city and people from all different countries tell me that I’ve made a difference. Sometimes, they even say I changed the world.”

This kind of thing is fun to read about for a paragraph or two, but Adams gives us five. Also, the implication that objections to obscenity are gaining ground seems to be just plain wrong. As noted, many signs point to increasing linguistic permissiveness in our country, a good example being the public reaction to the release of Donald Trump’s 2005 “pussy tape.” Many people (me too), seeing the tape when it was released, four weeks before last year’s election, concluded that, after this, Trump could not possibly be elected. We have learned otherwise.

As for Benjamin Bergen, his problem is that he cannot get over his joy in being naughty. Often, very often, he reminded me of a little boy who runs into the kitchen, yells “Fuck, fuck, doody, doody” at his mother, bursts out laughing, and runs off, expecting her to come after him with a rolling pin or something. There’s not a dirty joke in the world that he doesn’t think is funny.

In 2014, Pope Francis, trying, in his weekly Vatican address, to say “in questo caso” (in this case), ended up saying “in questo cazzo” (in this fuck [jb note: cazzo means "prick," not "fuck"]) instead. This was an understandable mistake. The two words are close, and the pope’s first language is not Italian. He corrected himself immediately.

Nevertheless, Bergen, in a chapter entitled “The Day the Pope Dropped the C-Bomb,” goes on and on about the supposed implications. Uttering a profane word like cazzo places the pope “in an ideological double bind,” he writes. And what might that be? Well,

if the curse word was accidental, then he’s just as linguistically fallible as the next guy, which isn’t necessarily the ideal public image for the professed terrestrial representative of God. Conversely, he might still be infallible, yet have intended to say cazzo. Again, likely not the image he means to project.

But clearly the substitution was accidental. Bergen just can’t bear not to have a good snigger over the pope’s saying fuck. Sometimes he seems to have written this book for teenagers. He explains what a syllable is, and a pronoun. He calls us “dude.”

So great is Bergen’s passion to liberate dirty words from censorship that he includes racial slurs among them. He says he has a principle—he calls it his “Holy, Fucking, Shit, Nigger Principle”—that almost all obscenities in English have to do with religion, sex, excretion, or ethnic difference, and he thinks that words in the fourth category deserve the same safe-conduct as those in the other three. He summons several old arguments, notably that people saying nigger are not using standard English but a different language, AAE, or African-American English (which seems to be the same as the “Ebonics” so argued over in the late 1990s), and that suppressing nigger means punishing the very people we are supposedly trying to protect, since users of AAE are primarily African-American.

But I think that lurking behind these arguments is another circumstance, the so-called “I’m offended” veto, which is causing students at our universities, and many other people, to demand that they be shielded from any information they might find disagreeable. Bergen hates righteousness, which, to him, I believe, would include all those who, when under the necessity of saying “nigger,” even to designate a word (e.g., “He said ‘nigger’”), not a thing (e.g., “He’s a nigger”), will substitute the phrase “the n-word”—a usage that seems designed not so much to avoid giving offense as to point to the speaker as a person who could never commit such a wrong. And like other recent commentators on this matter—Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt in their much-discussed essay “The Coddling of the American Mind” in The Atlantic of September 2015 and Timothy Garton Ash in his recent book Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World—he is worried that our brains will become enfeebled if we avoid disagreement and debate.

I applaud his sentiment. But he should not have tried to make this controversy parallel to quarrels over obscenity. Calling someone a fuck face is not nice, but it is meant to insult only one person. By contrast, a white person calling a black person nigger, the word the slave owners used, is insulting 13 percent of the population of the United States and reinvoking, in a perversely casual tone—as if everything were okay now—the worst crime our country ever committed, one whose consequences we are still living with, every day. (By the end of his discussion of slurs, Bergen seems to agree. I think his editor may have asked him to tone it down.)

As for fuck and its brothers, though, you can see Bergen’s point. Sometimes they are simply the mot juste, and even if you could come up with an inoffensive substitute, chances are it would be a lot less satisfying. Swearwords, as he says, are “good dirty fun.” Michael Adams, too, is fond of them and, more than that, feels that they emerge from a kind of shadowland in our minds and our lives—an intersection of anger and gaiety—that demands acknowledgment. Bergen is sometimes silly, and Adams sentimental, but both are on the right side.

No comments:

Post a Comment