Abigail Rockwell Jazz singer/songwriter; granddaughter of Norman Rockwell, huffingtonpost.com

[JB Note: For years I had hoped to organize, with a Russian friend, an exhibit comparing Rockwell and Russian "socialist realism" artists. The project -- arguably more a sociological/political rather than a strictly artistic one -- regrettably did not materialize, but some of my notes on Rockwell/Socialist Realists are available: (a) (b) (c) (d) (e).]

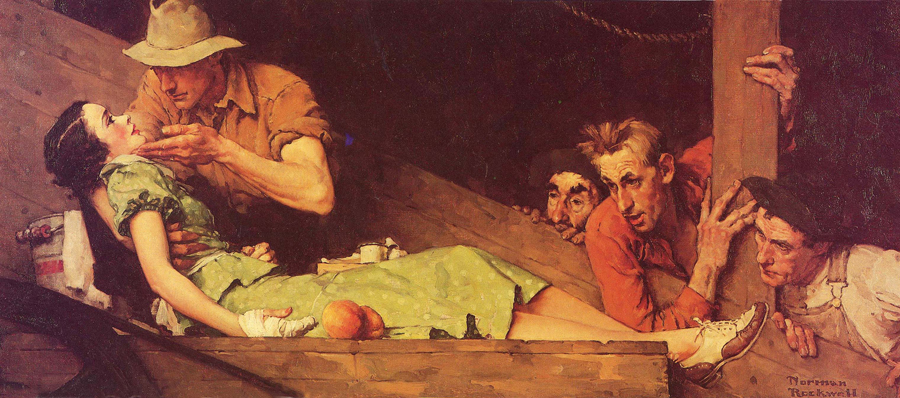

"Peach Crop," American Magazine, 1935 (Courtesy Norman Rockwell Family Agency)

Was Norman Rockwell an artist or an illustrator? My initial thought is, "Isn't every illustrator an artist?" Yet the debate continues -- especially when it comes to Norman Rockwell. The modern take on illustration is much too limited. A reevaluation of the medium through history is called for.

Thomas Buechner, director of the Brooklyn Museum, published his monumental book on Rockwell and his work in 1970:

"Norman Rockwell may not be important as an artist -- whatever that is -- but he has given us a body of work which is unsurpassed in the richness and variety of its subject matter and in the professionalism -- often brilliant -- of its execution. Unlike many of his colleagues (painters with publishers instead of galleries) he lives in and for his work and so he makes it important."

This statement is contradictory at best. It is the kind of ambivalence and confusion that follow my grandfather's work to this day. But Buechner then goes on to make an appeal that "illustration should be considered an aspect of the fine arts."

Admittedly, it is Rockwell himself who kept publicly pronouncing, "I'm not a fine arts man, I'm an illustrator." Two separate and distinct worlds and sensibilities. One of the reasons my grandfather led with this was emotional safety -- if he limited the way his artwork would be observed he could avoid the derision that might have come from the critics for trying to pass himself off as an artist with a capital A. He did this with other aspects of his work, such as his quips that he couldn't paint pretty, sexy women (this, of course, wasn't true, as evidenced by the many appealing women he painted throughout the years). He was humble to a fault.

Illustration is what Rockwell trained for. In my grandfather's mind, fine arts painters will not accept limitations or restrictions -- they are free to express themselves, encouraged to break all the rules. The illustrator is working not just to express him/herself but must work to please the client, art editor and the public. The illustrator's work is "meant to be seen in mass reproduction," the fine artist's "in the original" (Buechner). Rockwell embraced and accepted these restrictions. In fact, he thrived under these limitations and found ways to excel, grow and expand his work within, and in spite of, these confines.

Rockwell's artistic gods were Rembrandt and Pieter Brueghel. Rembrandt was great, according to my grandfather, because he was a great lover of humanity and that translated into his work in the most powerful way. What do we think of when we think of Rembrandt? The extraordinary faces and the incomparable light he captured. Rockwell revered Brueghel because he was a "great recorder of the times." Both observations could easily be applied to Rockwell's own work -- he was a great observer of human behavior, his love for humanity was an integral part of his art and, first and foremost, he was a storyteller:

"My life's work -- and my pleasure -- is to tell stories to other people through pictures... I try to use each line, tone, color and arrangement; each person, facial expression, gesture and object in my picture for one supreme purpose -- to tell a story, and to tell it as directly, understandably and interestingly as I possibly can."

He painted with the work of the masters all around him -- strewn on the floor, clipped on top of his canvas or tacked to the walls. Vermeer, Velasquez, Durer, Holbein, Klee, Rubens.

He looked to the Leyendecker brothers, Whistler, Homer, Rackham and Pyle for illustration inspiration. Howard Pyle was his guiding light when it came to the possibilities and potential of illustration; Pyle broke out of the mold to elevate the medium with a fresh authenticity -- his artwork is meticulously detailed and pulls you in. He expanded illustration beyond what it had been before.

Like Rembrandt, Rockwell found a way to capture light in a wholly unique, striking way. I noticed that most of my grandfather's memories in his autobiography are connected to light; light was emotion to him: in the midst of a nervous collapse in his teens he observed, "... the light faded along the walls, grayed, and was gone." In another memory, he said, "I watched the sunrise firing the river between the dark wall of houses on either bank. It looked like a scarlet lizard slithering in a coal bin." It is that awareness of light that is readily felt in all his work; it is one of the vital, subtle elements that creates a revelatory power that the viewer can viscerally feel when he sees the work in person. It is part of Rockwell's ceaseless drive to convey a powerful feeling or need in his art:

"This ability to 'feel' an emotion so intensely that you can project your feeling to someone else is one of the real joys of creative work. If you can do this, then you have creative ability."

He insists over and over again about the importance of focusing on the "original feeling" he wants to evoke and translating it onto the canvas. Thomas Fogarty coaxed Rockwell and the other students at the Art Students League in NYC to "Step over the frame and live in the picture." My grandfather tended to feel paralyzed by his emotions, but here he had finally found the perfect outlet for understanding and working through them.

To Rockwell, the human face was "the most important single element in any human interest picture," and when he would paint the head of a character he wanted to feel it: feel the structure of the skull beneath it... not just paint it, but "caress it." He didn't mind when people stopped by the studio if he was painting a background or an arm, but he didn't want any distractions or disturbances when he painted a head. Feeling, feeling, feeling. This drive extended to all his work, even the most commercial -- the advertisements. He didn't seem to give any job short shrift -- though some were more successful than others, of course. His early series for Edison Mazda lamps in the 1920's is dramatically effective and moving -- again, they are about electric light -- and light was emotion to Rockwell.

Like all great storytellers, from Dickens -- whose work had a profound influence -- to great movie directors like David Lean, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Rockwell's work was not completely "true to life," not photographically exact, but rather, he said, "the scene as I saw it." He was known as "The Kid with the Camera Eye," but his best work transcends the realism of photographs. When you study the photographs he used for each painting, you can see how he went past what they depicted and revealed his own truth beyond the photo. He understood the need for humor and pathos, the play between tragedy and comedy that he first discovered in Dickens.

"And the Symbol of Welcome is Light," Edison Mazda, 1920 (Courtesy Norman Rockwell Family Agency)

Rockwell's individual vision always ended with an affirmation of life, the essential resolution of all his work. His pictures were like Frank Capra's films in that way [JB note: Capra is of course well known for his WWII propaganda films]. No matter how much disappointment and struggle you may face, all will be well -- all is well. He produced his pictures much like a movie director would: Get the idea, then the actors, the sometimes lengthy search for costumes and props, and then direct the scene and throw yourself completely into the creation of the story you need to tell. Intensive research and an astonishing amount of preliminary work went into each painting: the idea sketch, then the charcoal sketch, in which he developed the story, then the color sketches -- finding the right color scheme to convey the mood -- then the layered process of the final painting, the under-painting on to the painstaking detail work of the characters, their clothing and the background. And naturally there were revisions along the way. At last came the fun of the final touches, which was something my grandfather particularly enjoyed, the stress of completion no longer nagging him.

How is Norman Rockwell not an artist? At his core, he was a true artist. And like all great artists he was high-strung, driven. Like tuning a guitar -- the strings must be tightened to arrive at the perfect pitch -- the artist has to be highly sensitized and attuned, inspired by something greater than he is. A laser focus is required to express a deeply personal longing that moves into a more universal need, ultimately a "resolution of an eternally familiar need," as Mark Rothko said.

What makes an artist great? Work that makes a great impact, strikes a resonant, resounding, lasting chord with the viewer, the audience. Many artists deal with the heightened sensitivity by escaping into addictions -- to alcohol, drugs, sex, food. They lose themselves in mental illness -- the mind and spirit break down from the high-wire tension. If Rockwell had an addiction, it was to his work; the smell of the turpentine, the feel of his brushes, squeezing a generous gob of Cadmium Red or Mars Violet onto his palette in the sanctuary of his studio. His work was unquestionably his greatest passion. Throughout his life he suffered several extended periods of depression -- not chronic depression -- and these were usually connected to struggles with his work. He would feel that he was not progressing, fueled by a nagging fear that his work would be perceived as "old-fashioned," out-of-date. Even at the height of his dementia at the end of his life when he had lost his abilities, he insisted on being wheeled out to his studio, where he would just sit and hold his brushes. It is what he knew. It was who he was.

Doesn't this make the charge of Rockwell being only a "recreationist," a "sentimental traditionalist" absurd and irrelevant? This extends into the endless debate about whose work is more valuable and lasting -- realists or abstractionists? Why is either art lesser than? Perhaps it is time to see beyond the imposed categorizations to the bigger picture of the importance of all art that has an impact. As a singer, to me it's like asking if Billie Holiday is more important than Renee Fleming. One, an unschooled jazz singer with an indescribable existential wail; the other, a technically brilliant singer who has trained her instrument to produce a clarion call of sublime longing and beauty. Both are equally important and essential as artists. Van Gogh admired Howard Pyle. Artists of all kinds have respected and been profoundly influenced by Norman Rockwell. True art fuels, sustains and inspires.

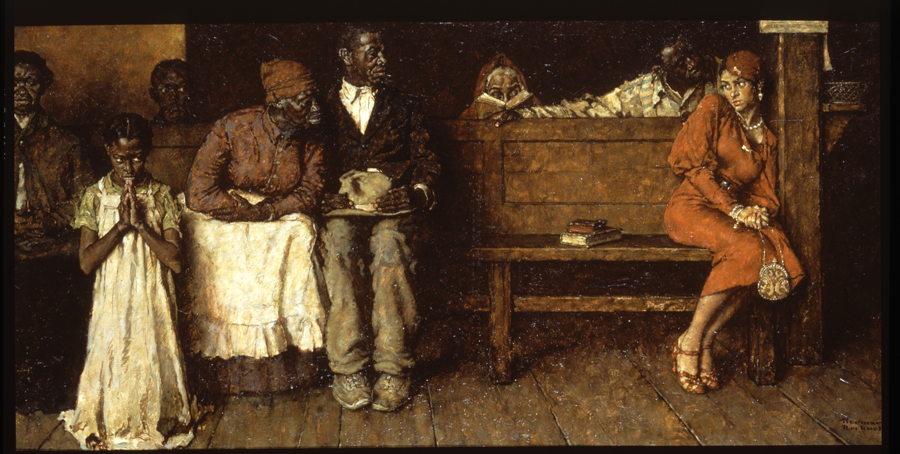

"Love Ouanga," American Magazine, 1936 (Courtesy Norman Rockwell Family Agency)

Rockwell himself divided art into three categories: fine art, illustration (covers and magazine illustrations) and commercial (advertisements and calendars). In truth, Rockwell was an artist with three distinctive sides. He aspired to paint like the masters and continually pushed his own envelope to improve, never resting on his laurels. There was the illustrator and storyteller, his artistic home. And then there was the necessity of being a commercial artist; this ensured that he survived financially.

His commercial work was sometimes too caricatured and sentimental -- the elongated limbs of the boys in his Four Seasons calendar, "Four Boys"(1951) is a perfect example of this. The only way to get to know the real Rockwell is to study his prolific body of work. Fine artists like Rembrandt and Michelangelo were storytellers and illustrators, too. The lines are sometimes nebulous, not always clear. All great art has its origin in illustration, from the cave paintings in Lascaux to the Egyptian pyramid paintings -- in particular the religious illustrations of the Middle Ages through the Renaissance and the tradition of genre painting -- all are examples of this. It is still not known if the cave drawings from almost 20,000 years ago were illustrations, stories or part of a spiritual ritual. Nevertheless, the downgrade of all illustration in this modern era is a step in the wrong direction, a modern construct that needs to be reexamined.

I found an unexpected ally in Mark Rothko, the abstract painter whose work is the antithesis of Rockwell's. Both trained briefly at the Art Students League and both studied with the renowned George Bridgman; Rockwell was born nine years before Rothko.

"It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted... There is no such thing as good painting about nothing," Rothko once said. He transcended the necessity of the figure by creating symbols and shapes in its place. His pictures, to him, were "dramas" conveying a fundamental, universal longing, illustrating the "condition of man."

In the two artists we see the ultimate abstractionist and the quintessential realist. Both driven, both with similar agendas in surprising ways, but a completely different mode of expression and conclusion -- Rockwell's ended with affirmation, Rothko's in "tragedy, ecstasy and doom." Both were gifted draftsman. One worked to improve that talent and reach a place of mastery with it; the other worked to break out and innovate. Rockwell needed the public to like him and his work -- connecting with the audience was essential to him. But fine artists like Rothko need acceptance also -- not on a mass level, but they cannot reach their audience without approval from critics, scholars, galleries, etc. All artists look to connect -- if they are truly good, that is. All other art is masturbatory and self-indulgent.

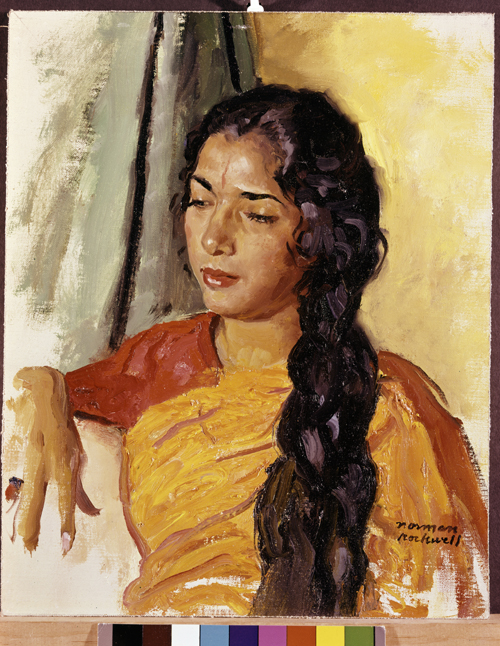

"Portrait of an Indian Art Student," 1962 (Courtesy Norman Rockwell Family Agency)

Approval and acceptance of Rockwell's work eluded him for many years. But the truth of his work still eludes many of the critics. The New York Times, for example, has a long history of denigrating his work. John Canaday dubbed Rockwell, the "Rembrandt of Punkin' Crick" in 1972. Michael Kelly branded him the "quintessential middlebrow American artist" in 1992. Before the "Pictures for the American People" exhibition in 2001 that traveled to the Guggenheim, the Corcoran and the High Museum -- an exhibition that illustrated the beginning of a critical reevaluation of his work -- Deborah Solomon, an art critic writing for the New York Times, belittled Rockwell's work in her assessment of "bad art" in her 1999 article, "In Praise of Bad Art":

"... nothing seems more outrageous than middlebrow art and the sort of pictures your grandmother savored -- the art, in short, of 100 percent normal Norman Rockwell... When you look beneath the surface in Rockwell, you find more layers of surface. What does it mean when ultrahipsters embrace an ultra cornball like Rockwell? You can see their stance as merely perverse, or you can see it instead as an honest vote for mass taste."

Solomon then goes on to compare the love of Rockwell's art to the appeal of cheeseburgers at Burger King.

(What's interesting to note is Solomon's complete reversal on everything Rockwell: her view on his art and person in her biography on him over a decade later. No art critic does a complete 360 without a powerful agenda driving them -- and it wasn't a genuine epiphany born of solid research.)

Lennie Bennett, art critic for the Tampa Bay Times, added her voice to the misleading assessments of Rockwell's work in March, 2015:

"... Rockwell never seems to stretch himself the way a great artist does. He avoids nuance and the complexities of relationships. The inner life holds no interest for him. But how fabulously he painted the outer life."

Neither Solomon, Bennett or the others seem to have made a comprehensive study of Rockwell's more than 4,000 paintings and 60 years of work, and they make definitive, generalized judgements about his work that are simply wrong. My grandfather searched for new techniques and concepts and utilized them throughout his career. There were pronounced shifts in his methods; Gottaist techniques in a different kind of paint, dynamic symmetry, he experimented with other artists' approaches, such as those of John Falter and Al Parker.

In the late 40's my grandfather learned a technique of the old masters, involving multiple glazes, when he was working at the Los Angeles Art Institute. An important shift occurred in his work after the Saturday Evening Post redesigned its cover in the early 40's to include full paintings instead of just vignettes with one or two characters and almost no background. That is when Rockwell's stories and technique took flight in a fresh, powerful way, leading to "The Four Freedoms" in 1943; afterwards, his pictures carried more serious subject matter.

One of the most astonishing things is to view all of his Saturday Evening Post covers from 1916 to 1963 in the downstairs room of the Norman Rockwell Museum at Stockbridge. The progression of his technique and vision from a promising beginning to mastery took me by surprise. When he reached 1950, coinciding with my grandmother's breakdown, a very dark time in my grandfather's life, his art evolved into something with unexpected layers of depth -- "Shuffleton's Barbershop" is one of his true masterpieces. Rockwell is the isolated, unseen observer looking through a cracked windowpane into the darkened barbershop, the musicians beyond his reach in the joy and light of creativity in a back room. An ominous, lone black cat sits in the shadows. This is "surface" art? Come on. Norman Rockwell's work rises significantly beyond what is known as "Rockwellian" when you study his work.

In Rothko's words:

"I hate and distrust all art historians, experts and critics. They are a bunch of parasites, feeding on the body of art. Their work is not only useless, it is misleading. They can say nothing worth listening to about art or the artist."

I recently visited the National Museum of American Illustration in Rhode Island. I don't know of any other museum that exhibits many of the leading illustrators together, side by side -- J.C. Leyendecker, Maxfield Parrish, Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, Mead Schaeffer, Charles Gibson, George Hughes and Stevan Dohanos, among others. As much as I admire his "Arrow Collar" man and technique, Leyendecker's work feels constricted and overworked; Parrish's landscapes of light are silent, shimmering revelations, though his characters are less fully realized.

Rockwell's work stood out in a pronounced way. Why? I came upon a painting I had never seen before, "Cat's Cradle" (1943), part of the Willie Gillis series. As I began to study the image, it was like a secret door had opened, a password was whispered, and the small mysteries and details became illuminated and revealed. The thread of the cat's cradle in Willie's hands stands out as almost three-dimensional through the texture created with the oils, the heightened white to draw the viewer in. The tiny blaze of brilliant orange of the mirrored cigarettes, the glint of the gold touches of the swami's earrings and adornments, the surprising depth and darkness of the background, the language guide put aside -- they are connecting without words. You are not just the observer anymore, you are there, part of the story. And that is the great impact of Rockwell's work: He connected with his audience, without words, for over half a century.

Another way he transcended illustration? Look at "The Problem We All Live With," Rockwell's celebration of the triumph of the Civil Rights movement with the story of Ruby Bridges. He made the radical move in taking off the heads of the marshals; they are visible from their shoulders down. They are not important, except as pillars of protection and support. Ruby is the focus. My grandfather dresses her differently: not in the dark dress and shoes with the white cardigan that she actually wore, but in the pristine white dress and shoes that illuminate the contrast with the color of her skin. He used two different local girls as models; he didn't just work from the photos of Ruby. She is a symbol of promise for all black children. He doesn't play it safe and creates a wall behind her with offensive epithets -- "Nigger," "KKK" -- but then in typical Rockwell fashion he paints an almost unseen love note to his third wife, Molly -- a tiny heart with "MP + NR" -- to counterbalance the hate.

Rockwell elevated illustration to a fine art, defying categorization. That is why he confounds critics and historians to this day.

I confess that for most of my life I remained ignorant of my grandfather's work. I did this to distance myself from what felt, at times, like an overwhelming legacy. I didn't even know the names of his most famous paintings and even, I think, unconsciously accepted the notion that Rockwell's art was overly sentimental and not "real art." I came to this recent investigation of his life and work with surprising objectivity and a fresh perspective.

"A laborer works with his hands,

A craftsman works with his hands and his mind,

But an artist works with his hands, his mind and his heart."

A craftsman works with his hands and his mind,

But an artist works with his hands, his mind and his heart."

~ From Louis Nizer

______

Abigail Rockwell is a jazz singer/songwriter. She recently finished the final draft of show she has written, called Torch Light, about deconstructing the concept of torch music. She has worked in voiceovers for years. Abigail joined the Norman Rockwell Family Agency to assist her father, Thomas Rockwell, a year ago in April. She has since left the agency and has written a comprehensive 62-page paper on the Deborah Solomon book -- extensively detailing the hundreds of errors and omissions.

No comments:

Post a Comment