via MT on Facebook

bbc.co.uk

By Stephen Ennis

Russian TV's relentless propaganda onslaught during the Ukraine crisis has not only turned large sections of the population against the West. It also appears to be having an effect on social relations inside the country.

Numerous stories have emerged in the media over the past year of how state TV's highly emotive coverage of Ukraine has turned friends and family members against each other, leading in some cases to serious breakdowns in communication.

It also seems to be creating a society with an appetite for war and aggression.

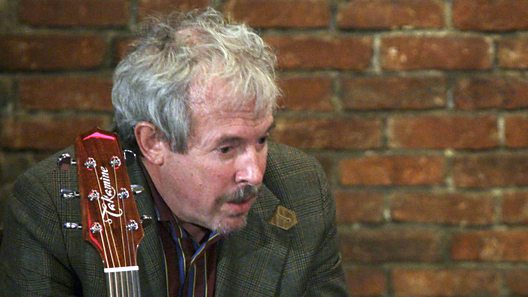

Musician Andrei Makarevich is among many liberals attacked by state TV over their stance on Ukraine

Last summer, Gazprom-Media's NTV ran a series of programmes attacking Russian celebrities and politicians seen as sympathetic to the new government in Kiev.

One was called "13 friends of the junta" and began with footage of veteran rock star Andrei Makarevich performing a charity concert for displaced children in the town of Svyatohirsk in government-controlled east Ukraine.

But according to NTV, the concert was a cynical ploy to revive Makarevich's flagging career and was somehow timed to coincide with a Ukrainian army offensive.

Cue a sequence in which Makarevich's guitar chords were synched with artillery volleys and culminating in a massive fireball of destruction. Two of his Russian music business colleagues were then shown denouncing him as a "traitor".

It was a classic state TV smear, but also a clever piece of psychological manipulation.

'Propaganda carpet-bombing'

In an article published on Latvia-based website Spektr just a few days later, Moscow family psychologist Lyudmila Petranovskaya described how Russian state TV tries to get inside people's heads.

"One can say that over these past months Russian viewers have been subject to mass emotional rape, propaganda carpet-bombing," Ms Petranovskaya wrote.

"The point here is not to impart a certain point of view. Reports and messages are constructed so that the viewer understands that he himself should make a moral choice."

The effect of this intense bombardment can be seen in the sharp rise of anti-Western sentiment captured in numerous opinion polls. But it also appears to be having an impact on people's personal lives.

Ms Petranovskaya said her post-bag had been filled with letters from people asking in different ways the question: "What's happened to them?"

Some wrote of pleasant elderly neighbours who out of nowhere and "with hatred and rising blood pressure" started ranting about the "bloody Kiev junta".

Others, she said, were astounded to find friends, who they had thought of as intelligent and ironic, launching into diatribes about how President Putin had "raised Russia from its knees".

'Zombified'

Ms Petranovskaya was writing a year ago. But similar stories continue to emerge today.

In an interview with the liberal website Colta, TV producer Stanislav Feofanov said his mother had been "zombified" by propaganda to such an extent that the only thing he could talk to her about were "domestic details".

The effects of Russian TV propaganda have been compared to the nightmare scenarios of Stephen King

Case histories recorded in an article on the social activist website Takiye Dela echoed Feofanov's experience.

"Anna" (not her real name), who edits a magazine in London, spoke about how her mother started calling her an "enemy of the people" because she had published an interview with one of President Putin's opponents.

For both her parents, the "correct opinion has become what is said on TV", she said.

The situation was all more the perplexing for "Anna" because her parents were "educated, intelligent people" who had supported the reforms of the 1990s and at the last presidential election had voted not for Vladimir Putin, but his liberal opponent, businessman Mikhail Prokhorov.

Moscow student "Lena" had similar problems with her 78-year-old grandfather, who had also appeared until recently to be liberal and open-minded.

When she declined his invitation to watch a film on state TV about Putin, he waved her away muttering: "How did I raise a fifth column in my own home."

But it is not just a generational divide. "Ivan", an IT specialist from Samara, described how he had grown apart from his wife of 11 years because of her support for Putin's actions in Ukraine.

"We are both afraid to make any comment at all about the news, even though we used to be able to discuss politics calmly," he said.

'Unthinkable'

This kind of breakdown in communication was also noted by sociologist Karina Lipiya of the Levada polling organization.

"People generally do not want to hear another point of view," she told Radio France Internationale's Russian-language website.

State TV presenter Konstantin Semin predicts a propaganda escalation

Her Levada colleague Alexei Levinson noted how significant numbers of Russians were now entertaining thoughts that "until yesterday were unthinkable and unacceptable".

As he wrote in business daily Vedomosti in April, 47% men said Mr Putin's statement about being ready to use nuclear weapons "did not make them fearful". A large proportion of young people (40%) also thought Russia could defeat the United States in a nuclear war, he said.

Mr Levinson linked these bellicose opinions to the influence of television.

Recent research suggests that Kremlin TV propaganda may have declined in popularity from a peak in the summer and autumn of 2014.

But Ukraine still dominates the TV news, and talkshows where guests rant about US plans for world domination continue to command large audiences.

For veteran TV critic Yury Bogomolov, this suggests that many Russian people have somehow become "addicted to propaganda" and now have an "appetite for aggression".

"There is a cycle of hatred in our society," he wrote in a blog on the website of independent radio station, Ekho Moskvy.

More to come?

Vedomosti's Maxim Trudolyubov reached a similar conclusion, suggesting that TV propaganda now induces a form of "intoxication" in the viewer.

He also stressed that pro-Kremlin TV's apparent power to exert such phenomenal influence over large numbers of Russians was not because of an absence of available alternatives, as was largely the case in the USSR.

TV would not be so "pre-eminently successful" at this if the "citizens did not want it to be", he wrote.

Both Ms Petranovskaya and Trudolyubov have likened the effects of TV propaganda to scenarios in novels by the US author, Stephen King.

Ms Petranovskaya alluded to "Cell", in which a mobile-phone signal turns previously normal people into savage zombies.

For Trudolyubov, the alternative reality created by Russian TV was reminiscent of the small town cut off from the outside world in "Under the dome".

The scale and intensity of the current propaganda campaign is unprecedented in modern Russia. One would probably have to go back to the Stalin era to find anything comparable.

But there may be more to come - certainly, if state TV presenter Konstantin Semin gets his way. Writing on the Odnako website, Semin said that what passed today for ideology on state TV was a mere hotch-potch of liberalism and patriotism with a sprinkle of Soviet nostalgia.

But if things really get tough, he said, the state will have to overhaul the media and develop a proper "mobilising ideology - the ammunition for propaganda artillery".

No comments:

Post a Comment