Alia E. Dastagir, USA TODAY

JOBS, JOBS, JOBS!"

The exclamation was part of President Trump's tweets last month, hammering home a promise that helped get him elected.

But the unemployment rate is (and was before the election) between 4 and 5% which many economists consider full employment. The U.S. had a record 75 straight months of job growth under President Obama. The poverty rate has decreased from 19% in 1964 to 13.5% in 2015, according to the Census Bureau.

So why do American workers feel worse off? Why does lamenting the state of work seem right?

In the last half century, economic, political and social changes have altered not only the makeup of the workforce, but also what it takes to get a job and support oneself, let alone a family.

What's changed?

"What's changed? Everything's changed," said Alice Kessler-Harris, a Columbia University professor who focuses on gender and labor history.

► Once dominant industries, like manufacturing — which paid well even without a college degree — have been overtaken by service sector jobs, most of which are low-paying, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. At the same time, knowledge-based jobs, which exclude lower-skilled workers, are continuing to grow.

“The boundaries of who's legally and culturally considered a worker are redrawn persistently," said Jennifer Klein, a Yale University history professor and author of Caring for America: Home Health Workers in the Shadow of the Welfare State.

► The cost of getting a college degree is up more than 1,000% since 1978, according to Bloomberg. Millennials are saddled with more student loan debt and, despite being more educated, earned 20% less in 2013 than Boomers did at their age in 1989, adjusted for inflation.

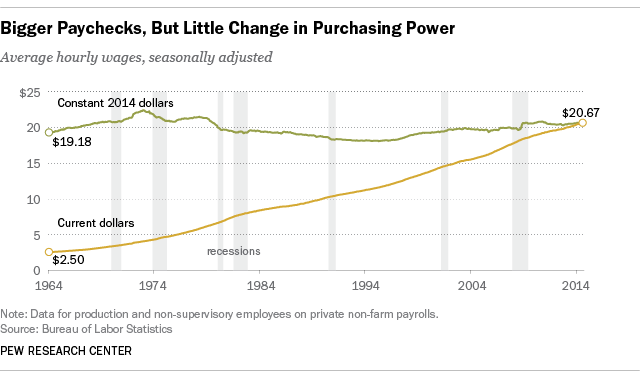

► Decades of stagnant wages mean both parents must often work to make ends meet, creating a need for child care and elder care that didn't exist in 1950, for example, when two-thirds of women were full-time "homemakers" aka caregivers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Women now make up nearly half of the U.S. workforce, but are paid less than men on average in the same jobs, according to the non-profit Institute for Women's Policy Research.

► The power of unions has waned, which some research suggests has contributed to lower pay for non-union workers, too, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

► The gig economy (Uber, Airbnb) has exploded, giving workers more control and flexibility, but fewer benefits or legal protections.

The result?

America's work structure doesn't work with many realities of American life.

Americans fear that demands of work mean they don't spend enough time bonding with their children, connecting with their spouses or caring for themselves. Many workers are emotionally and financially drained from juggling the health costs of aging parents and childcare needs of growing families. Americans are constantly arranging and rearranging the puzzle pieces of work, family and (if they're lucky) leisure that never seem to fit quite right.

"You end up with this perfect storm where workplace and public policies are mismatched to what the workforce and families need," said Vicki Shabo, vice president at the non-partisan National Partnership for Women & Families (NPWF).

Paid leave: Little to none

More than 60% of Americans say they've either taken or are very likely to take time off from work for family or medical reasons, Pew Research Center reported in March. However, fewer than 40% of workers qualify for the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), according to the NPWF, and those that do are guaranteed 12 weeks of unpaid leave — far less than workers in other industrialized nations.

MacKenzie Nicholson was pregnant with her second baby when she found out her mother had a brain tumor. She was forced to take time off to care for her, which cut into the vacation and sick time she was saving to supplement the three weeks of paid maternity her company offers. She knew she needed 6 weeks to medically recover from a scheduled C-section.

"It's not just having a baby," she said. "It's taking care of a sick parent. These kinds of life events don't discriminate. There are so many things that happen that we can't expect or plan for. I don't think it's right to almost punish an employee for trying to do what's best for their family when we all have families. It's a dangerous thing that we do."

Bills on both sides of the aisle have been introduced to address the need for paid leave. The GOP-backed Strong Families Act, first introduced in 2014, was reintroduced by Sen. Deb Fischer (R, Neb.) in February. The bill would provide tax credits to encourage companies to offer employees at least two weeks of paid leave per year. Employers would receive a tax credit equal to 25% of what they pay employees during their leave.

The Democrats plan, reintroduced in February by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D, N.Y.) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D, Colo.), is The FAMILY Act, which would create a national fund to provide workers with two thirds of their income for up to 12 weeks, no matter where they live or work. The Democrats' proposal would be funded by employee and employer payroll contributions, averaging less than $1.50 per week for a typical worker.

The paid parental leave plan Trump proposed in his 2018 budget would cover mothers, fathers and adoptive parents for six weeks. Championed by the president's daughter Ivanka Trump, the plan is the first of its kind to come out of a Republican White House. However, it's up against a Republican-controlled Congress that supports few new domestic expenditures.

Childcare: Hard to find and fund

For working parents, finding and paying for childcare can be a punishing process. One in three parents say it’s difficult to find child care, according to a 2016 poll from NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. And once they do find it, cost can be a significant burden. Nearly a third of parents who have a fee for child care say the cost has caused a financial problem for their household.

Marine veteran Charlotte Brock was working at a Washington, D.C., think tank and going to school full-time when she found out she was going to become a single mom. Her company did not offer paid maternity leave.

Brock said that the high cost of childcare in Washington, D.C., — over $2,000 a month — was one of the reasons she decided to pause school, quit her job and move back in with her parents.

For two years she stayed home with her son. Eventually, she went back to school, and began the difficult work of trying to re-establish her career. Her mother helped fill in the gaps with her son's childcare when she was at work or school.

"If it weren't for my mom, I don't know how I would have done anything," she said.

Brock eventually received her masters in industrial organizational psychology from George Mason University and now works at NASA's Office of Inspector General, though she says her career has never recovered from the time she took off after having her son.

"At my high point, I was making almost $30,000 more than what I'm making now," she said.

"I'm disgusted by our country's lack of morality," she said. "Of not putting families first, of not putting babies first, especially those who tout family values and then don't do a thing to actually support families."

Trump said he wants to make child care more affordable, though an analysis from the non-partisan Tax Policy Center found his plan is likely to benefit mostly wealthy families. The report found 70% of the benefits will go to families that make $100,000 or more and 25% will go to people earning $200,000 or more, with few benefits going to the lowest income families who struggle to pay for child care, and who stand to benefit from it the most. Those making below $40,000 would save just $20 or less per year.

Always-on culture

In the U.S., the average workweek is now 34.4 hours, according to data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), but Shabo says this does not necessarily reflect the realities of work at both the highest and lowest ends of the economic spectrum.

“For many families, there is no 40-hour work day or five-day work week,” she said. “That’s both for the knowledge-economy workers who are working all the time, for whom flexibility may be leaving in time for dinner but getting back online, and it's also for that other huge share of Americans who don’t have enough hours to work, who don’t know when and where and for how long they will be working, who can’t sync up their child care or educational opportunities with one or two or three jobs."

Longer commutes

The Census's 2015 American Community Survey data found the typical American commute keeps getting longer, with a growing body of evidence showing the negative effects those commutes have on workers’ health and emotional well-being. People with long commutes are more likely to say they are obese, have high cholesterol and neck or back pain.

Minimum wage

According to Pew Research Center, 58% of Americans are in favor of raising the federal minimum wage — which, at $7.25 per hour hasn’t budged since 2009. A parent earning minimum wage, even if they can get enough hours to be considered full time, struggles to stay above the poverty line.

Labor groups have been pushing to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. There are few details on whether Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta supports raising the minimum wage. Trump's position on the issue has shifted. He has said both that the minimum wage should not be increased, and that he doesn’t “know how people make it on $7.25 an hour.” Some states and municipalities are at or closing in on the $15 level.

Overall progress for workers has been slow, Shabo says, because the country is attached to an “ideal myth of America." One where you pull yourself up by your bootstraps.

“You think about your family challenges as individual problems,” she said. “Not as a thread that really does bind virtually everybody together in one way or another.”[JB emphasis]

***

For details on the "E Pluribus Unum?" presentation, see.

No comments:

Post a Comment