Are Crimeans really Russian nationalists and separatists?

Posted on February 24, 2014 by VOSTOKCABLE Via MP on Facebook

With Ukraine’s protests apparently lacking the support of much of the country, attention has again focused on Crimea – an ethnically Russian region described by some as ‘the dog that didn’t bark.’ According to Ellie Knott, who studies the region, concerned journalists are only telling half the story.

The majority of the news pieces written about Crimea follow the same logic. Following the 2008 crisis in Georgia, Crimea was described as “the next South Ossetia”, Ukraine’s “Achilles heal” and “Russia’s next target.” Similarly in recent weeks, there has been a connection drawn between Crimean violence in the 1990s and its call to secession with the idea that it “has a strong Russian identity”. However, the lack of engagement with people on the ground means many observers miss much of what has happened since 1991.

Such a logic uses the 2001 census in support to suggest that the majority of the Crimean populace (almost 15 years ago) identifying as ethnically Russian is an indication of the state in which the majority would like to live. This has further entrenched the notion of Crimea as a peninsula of hotbed Russian nationalism waiting to secede. An article in RFE/RL recently tried to suggest that Russian nationalist separatism was increasing in Crimea based on an interview with a long known, and infamous, Russian nationalist Sergei Shuvainikov.

However, as Gwendolyn Sasse indicates, the Russian nationalist movements reached a crisis point in 1994 from which they never recovered because of their conflicting aims. Therefore to have any idea about the depth of this nationalist sentiment, it is necessary to talk to those outside of the Russian separatist movements, and in particular with everyday normal people, to see how far this idea resonates.

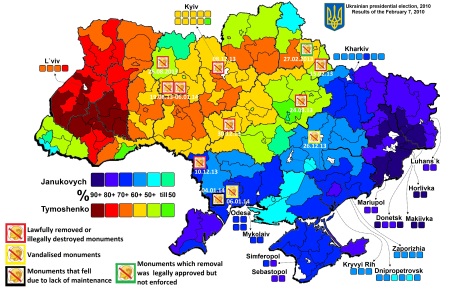

Interestingly, in around 50 interviews I conducted in Simferopol, the capital of the Autonomous Region of Crimea, in 2012-2013, I discovered that there was a general feeling that the chaos of the Russian nationalist movements had never really subsided. Organisations like Russkaia Obschina Kryma (Russian Community of Crimea) and the Crimean party, Russkoe Edinstvo (Russian Unity), continued to fail as a result of the infighting between their contrasting characters, some wanting to use the movements in support of their personal aims against their rivals, but less against mainstream politics. Local election results support this, with Russkoe Edinstvo consistently winning few seats and far behind the majority Party of Regions, and even the Communist Party.

I also found a plethora of different opinions regarding what it meant to be Russian. Indeed, many young people preferred to identify politically as Ukrainian instead of any ethnic identification. These young individuals described a big shift between themselves and the older generation including their parents, who identified as Russian. In comparison these young people identified as “more Ukrainian” and “Ukrainian citizens first” because they had been born in Ukraine, so that to them Russia was somewhere foreign. Yet they described how once in the peninsula you would identify as Ukrainian only if you were ethnically Ukrainian, and probably born elsewhere in Ukraine, whereas for the post-Soviet generation they would identify as Ukrainian based on their citizenship and place of birth.

There certainly was a significant number who identified as ethnically Russian, but in my research I split this between two categories: ethnic Russians and discriminated Russians. The discriminated Russians were a small group, mostly aligned with the Russian nationalist organisations discussed above, who identified not just as Russian but as anti-Ukrainian and as victims of Ukrainisation policies. In contrast, there were a far greater number who identified as ethnically Russian but without any sense of discrimination by Ukraine. These individuals were able to reconcile their ethnicity with residing in Ukraine, feeling that they were part of a normative project in which they wanted to be able to speak Ukrainian, as the state language, more proficiently.

Generally, the overwhelming feeling of those outside the discriminated Russians was that the feeling of discrimination in the peninsula and in Ukraine was unjustified given that Russian could be spoken freely (indeed, in 2012 Russian became a second state language in a parliamentary vote that invigorated Ukrainian nationalist movements in Kyiv and L’viv). Moreover, there was the feeling that ethnicity and language were not related to quality of life, because in Crimea and Ukraine “everyone lives badly”. Using the 2001 census is therefore tenuous because of the amount of change in the peninsular, in particular among the post-Soviet generation, and because of the fuzziness of identity which does not pair neatly with the hard and mutually exclusive census categories of ethnically Russian and ethnically Ukrainian.

On the issue of passports, during my first trip to Crimea in 2011, I expected to hear that everyone was acquiring Russian citizenship. However, in my interviews no one indicated that they had acquired Russian citizenship, in part because both Russian legislation and Ukrainian legislation prohibits it and because interviewees had no interest or need for Russian citizenship. I shifted therefore in 2012 to look at the use of the Russian Compatriot policy, which facilitates migration to Russian regions and offers a few scholarships in Russian universities. The story was largely the same: a lack of interest and knowledge of what Russia was offering, outside of those involved with Russian organisations, and an absence of identification with the discourse of the policy. As two interviewees discussed, they did not identify as “compatriots” of the Russian Federation but rather compatriots of each other because they were from Ukraine.

There should be caution with regards to how evidence is used about Crimea and what conclusions are drawn from this. I would argue that the biggest issue facing Crimea, and southern and eastern regions of Ukraine more generally, is the vacuum that might be left from the disappearing power vertical of the Party of Regions, and not from weak Russian separatist movements.

No comments:

Post a Comment