SETH FREED WESSLER, nbcnews.com

The professor at the head of your college classroom may be on food stamps.

In search of cuts to their bottom line, American colleges and universities are using part time instructors to teach classes that a generation ago would have been the responsibility of tenured professors.

Paid as little as a couple of thousand dollars for each semester-long course, hundreds of thousands of people with doctorates or multiple master's degrees are earning near-poverty wages working as adjunct professors. And as a result, one in four families of part-time college faculty are enrolled in at least one public assistance program, like food stamps, Medicaid or the Earned Income Tax Credit, according to calculations of Census data by researchers at University of California, Berkeley's Labor Center.

"We're seeing a second class status of professors emerging," says Carol Zabin, Director of Research at the Berkeley Center. "More broadly, professional occupations have increased contingency and low pay."

Berkeley also found:

- 1 in 5 families of part-time faculty receive Earned Income Tax Credit payments.

- 7 percent of families of part-time faculty members receive food stamp benefits.

- 7 percent of adjuncts and 6 percent of their children receive Medicaid.

- Families of close to 100,000 part-time faculty members are enrolled in public assistance programs.

All of this amounts to a not-insignificant public cost, the Berkeley researchers found:

- The taxpayer cost of public assistance for families of part-time faculty is nearly half a billion dollars per year ($468 million).

- More than half of these costs, or an average of $274 million per year, is spent on Medicaid.

Alyssa Colton has been teaching college for nearly two decades. When she landed a full time job at the College of St. Rose in Albany, New York, in 2008, she was hopeful it might lead to the kind of tenured professorship that Colton's father, a medical researcher, had when she was a kid in Syracuse, New York. Colton has a Ph.D. in literature from the State University of New York.

When Colton's contract ended in 2012, no permanent offer followed. With a mortgage to pay, a husband whose business had recently failed, and two teenage daughters, Colton started looking for other teaching work. She took a part-time job as an online tutor for a semester, not what she imagined her job would be with a doctorate, and then filed for unemployment.

A semester later, Colton was offered another gig at St. Rose, teaching some of the same English and writing classes she'd taught when she was hired in 2008. This time, however, she worked as a part-time adjunct professor for a fraction of the pay and without the healthcare or retirement benefits that her full-time position had provided.

"I essentially took a pay cut," Colton said, "doing the same work for less money and less respect."

Colson earns $3,200 for each four-credit class she teaches. She estimates that she earns less than $10 an hour after all the course preparation and office hours answering student questions.

"I could go work at Starbucks," she said. "I understand they pay about $10 an hour too."

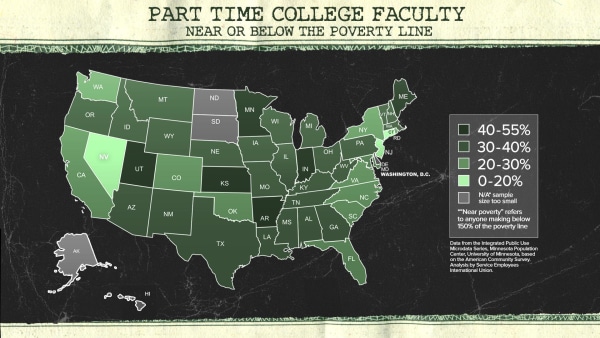

Professors in Poverty

Nearly a third of all part-time faculty have an income that is less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level, far above the average for all Americans. The same is true for just five percent of full time college professors, according to Census analysis by the Service Employees International Union. SEIU has been actively organizing adjunct professors in dozens of colleges around the county, including at St. Rose.

The United Auto Workers and the American Federation of Teachers are organizing on other campuses. On April 15th, adjuncts on many campuses will join workers from dozens of other sectors including fast food and retail workers to call for raises.

But the trend toward greater worker insecurity has continued even as more adjuncts attempt to unionize.

To support her family, Colton, whose husband's small business went under several years ago, uses food stamps, about $600 a month, to buy groceries for her family. She and her children are enrolled in Medicaid. Last year their family income was so low that they pulled in several thousand dollars from the Earned Income Tax Credit, a program for poor families.

"I didn't think that getting more education would lead to harder times," Colton said.

Supplementing her income with online tutoring work, and sometimes picking up a class at the nearby community college, Colton earned $27,000 last year, just over the poverty line for a family of four. Her house is now in foreclosure.

A different life

Had Colton entered academia a generation ago, she would likely have been living very differently. In 1975, nearly 55 percent of college faculty held full-time tenured or tenure track jobs, according to a 2014 report by the American Association of University Professors. In 2011, fewer than 30 percent of faculty held similar jobs.

The average starting salary in the U.S. for a full-time, tenure-track professor is around $65,000 a year. For tenured professors, it's $95,000.

Part-time jobs now account for over half of all professor positions. Another 19 percent of faculty are employed full time but without any hope of gaining the security of tenure.

College of St. Rose's Director of Media Relations Benjamin Marvin says that tenured and tenure-track instructors still teach the majority of the college-course hours — around 70 percent. He added that many adjunct instructors do not want full-time faculty jobs and teach in addition to other professional careers. Still, contingent instructors are comprised largely of academics who entered graduate school aspiring to full-time, stable work.

Growing contingency in the ranks of college instructors, says Daniel Maxey, co-director of the Delphi Project on the Changing Faculty and Student Success at the University of Southern California, is a result of "economic changes such as dwindling public resources allocated to fund higher education, rising corporate influence in the way institutions are managed [and] demands of growing enrollments and access to higher education," among other factors.

The fallout of these changes travels beyond adjunct's own financial stability. Research has shown that the quality of instruction declines as teaching work is shifted from full time to adjunct professors.

"I have less time to prepare for classes, and can't be as present for my students," said Colton. "This isn't good for anyone."

No comments:

Post a Comment