historians.org

via IK on Facebook

Robert B. Townsend, December 2015

Attend almost any reception at the AHA annual meeting, and you are likely to hear someone complain that their subject area is unusually beleaguered in the discipline—suffering from shrinking ranks and limited job opportunities. But are these mere anecdotal impressions or accurate perceptions of changing realities in the discipline?

A survey of 40 years of field specializations confirms the impression among some (such as specialists in European and intellectual history) that their specialties are losing ground in the discipline, while also demonstrating the gains of many other fields on long trajectories of growth in the discipline (such as women’s history and histories of parts of the world outside the Northern Hemisphere) and those rising quickly in recent years (specialties in history of the environment and sexuality).

The listings of US history faculty in the AHA’s Directory of History Departments, Historical Organizations, and Historians (previously the Guide to Departments of History) offer a window on the specializations of historians—albeit primarily at four-year colleges and universities—for four decades.1Even if a tabulation of the specializations used to designate faculty over that span cannot explain why particular fields may be rising or falling, much less changes in the underlying meanings of particular labels and relationships between fields, a textual analysis of the faculty listings can at least provide a measure of the changes and a basis for further self-examination (if not angst).

Topical Specializations

In the 2015 Directory, 15 topical fields of specialization reached a minimum threshold of at least 2 percent of all listed history faculty.

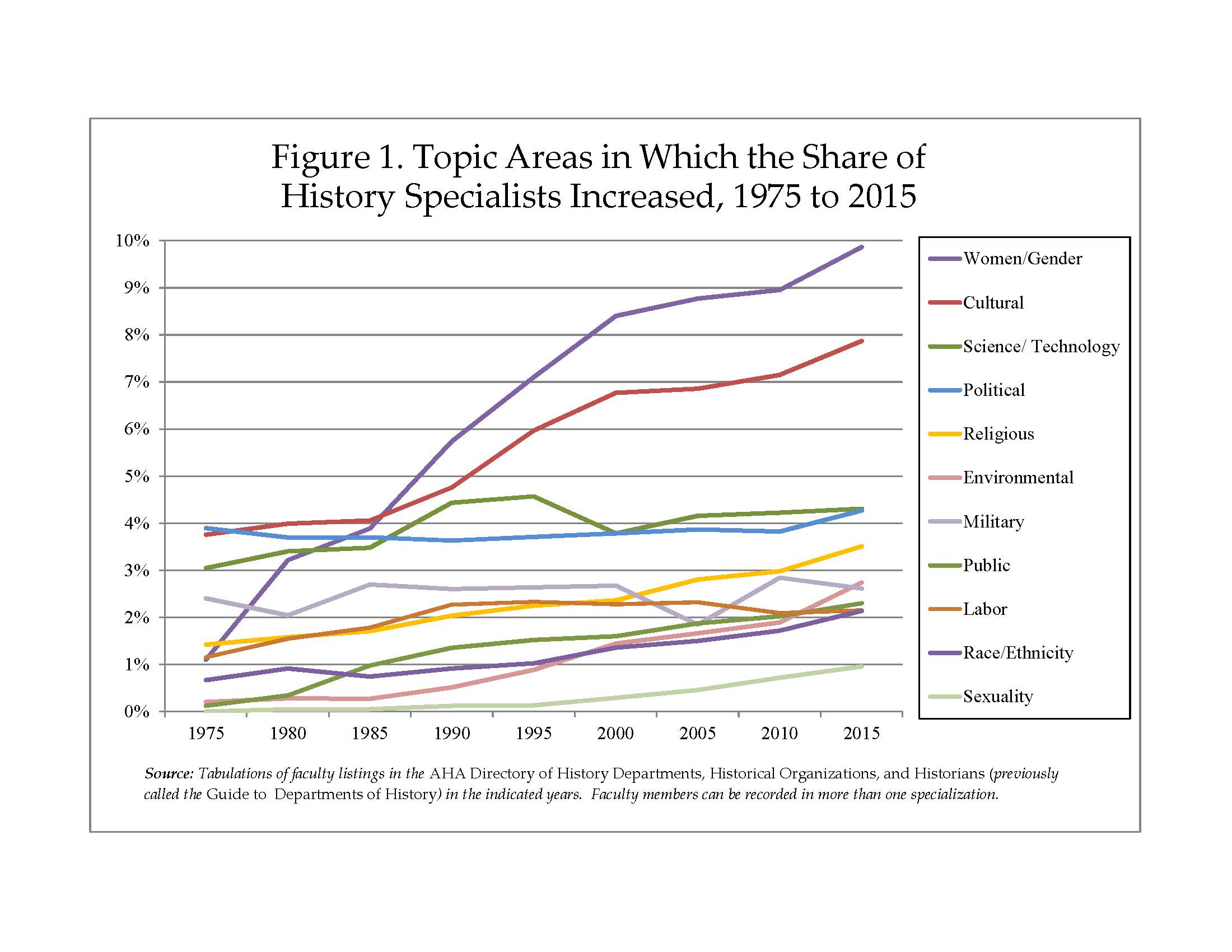

Eleven of these topical fields grew in the past 40 years, as measured by faculty listings in the Directory (fig. 1). The field with the largest proportional expansion was environmental history—from 0.2 percent of the listed faculty in 1975 to 2.7 percent today. That may still seem like a small number, but the share of departments employing an environmental historian grew from 4.3 percent in 1975 to 43 percent in 2015.

Other topical specializations showing substantial growth were histories of culture (up 109 percent since 1975), religion (up 147 percent), race and ethnicity (up 220 percent), and women and gender (up 797 percent).

Interestingly, military history has a larger share of faculty than it had 40 years ago, but it has experienced a reversal in the past 5 years. After the share of faculty reported in the field increased from 1.8 percent in 2005 to 2.8 percent in 2010, the percentage fell slightly (to 2.6 percent) in 2015. (The share of departments with a specialist in the field held steady at 37 percent from 2010 to 2015.)

Public history, which combines both topical and professional dimensions, had the fastest growth of any field in the 1975 Guide—rising from 0.1 percent of the listed faculty to 2.3 percent today. The share of departments with a public history specialist expanded from 1.7 percent to 30.8 percent over the same span. The comparatively new topical/professional field of digital history was ascribed to 0.3 percent of the listed faculty in 2015 and was represented at only 5.6 percent of the listed departments.

Alongside the growth among the larger topic areas, the history of sexuality had the fastest recent increase—rising from 0.1 percent of the listed faculty in 1990 to 1 percent today (with representation of a specialist in departments rising from 2 percent to 18 percent over the same time period).

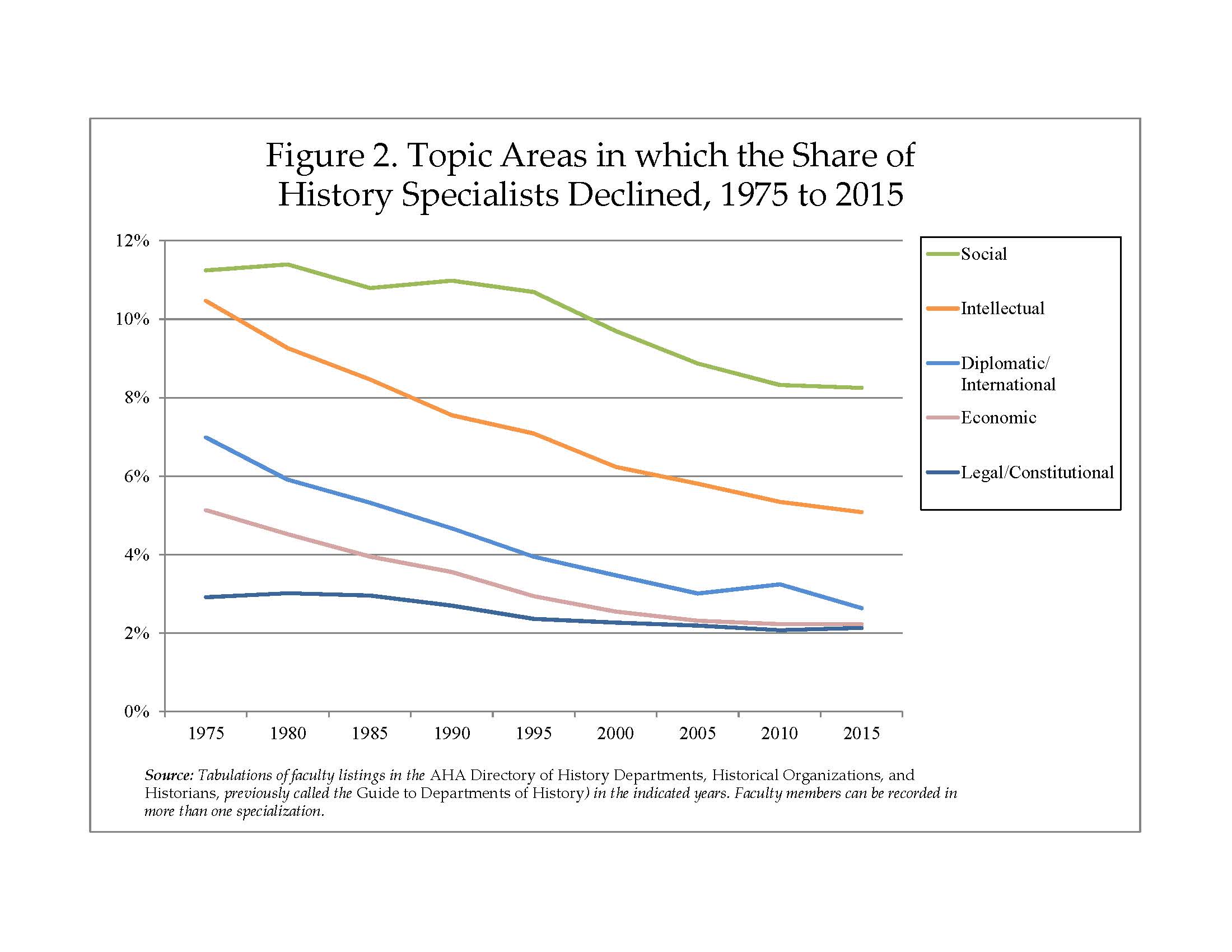

While two-thirds of specializations increased their representation among faculty and departments in the Directory, five others experienced a substantial drop in their share of faculty, with diplomatic, economic, and intellectual history all falling to less than half of their percentages among faculty 40 years earlier (fig. 2). The shares of specialists in legal and social history both fell by 27 percent over the same span.

The share of departments with at least one subject specialist in all five fields also declined over the past 40 years. The total number of departments employing a social historian dropped 7 percent since 1975 (to 68 percent of all departments), while diplomatic history’s representation rate dropped a precipitous 41 percent (to 44 percent of all departments).

Nonetheless, these five fields may be primed for revival. The trajectory of decline for each has slowed in the past 10 years, and the share of specialists in legal history actually rose over the past 5 years. And even though the share of specialists in economic history continued to shrink, the share of departments with at least one specialist in the subject increased slightly over the past 10 years (from 31 to 32 percent of all listed programs).

Trends among Geographic Fields

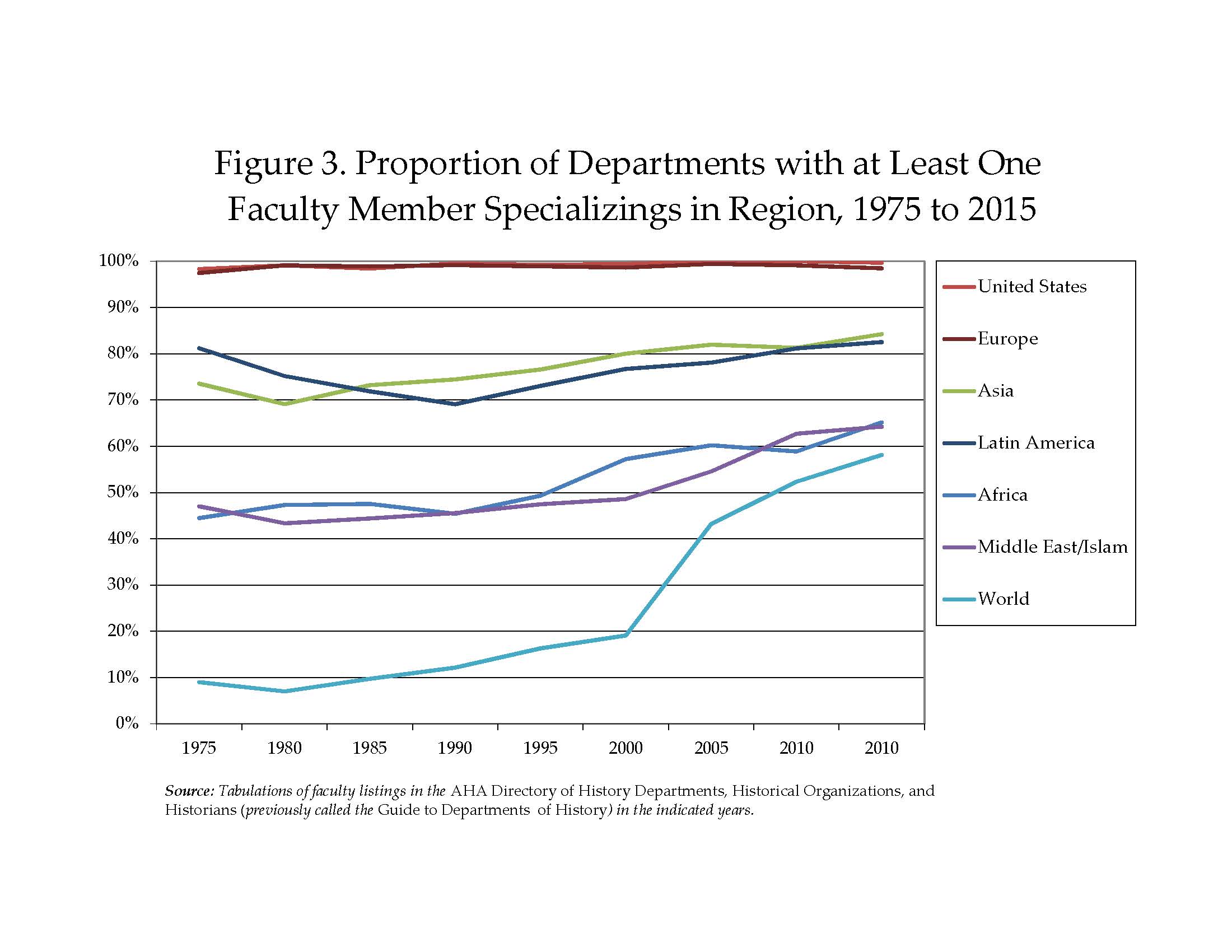

Viewed over the past 40 years, the most notable change in history faculty has been a modest rebalancing in the distribution of geographic field specializations. In 2015, the share of specialists in European history fell to its lowest level in the past 40 years, shrinking to 32.2 percent of the listed faculty (from a high of 39 percent in 1975; fig. 3). The percentage of specialists in US history increased slightly (from 41.0 to 41.2 percent), but remains near historic lows.

In contrast, the shares of faculty specializing in all other continents reached their highest level in the past 40 years. Asian history continues to have the largest percentage of faculty outside of the United States and Europe, reaching 9.4 percent in 2015. Specialists in Latin American history accounted for 7.4 percent of the listed faculty, while shares of specialists in the histories of Africa and the Middle East/Islamic world both approached 5 percent.

The larger shares of faculty specializing in areas of the world outside the United States and Europe may understate the substantial expansion of their representation of faculty in departments over the past 40 years. Specialists in Asian and Latin American history can now be found in more than 82 percent of the departments listed in the Directory for the first time. And specialists in the history of Africa and the Middle East can now be found in nearly 65 percent of departments.

World history has grown faster than all other geographic specializations—from 1 percent of the faculty listed in 1990 to 5.1 percent today. And specialists in the subject can now be found in 58 percent of departments, up from less than 20 percent as recently as 2000.

Variations in Age and Employment Status between Fields

The often gradual changes over the past 40 years offer an indication of the ways hiring decisions of one generation can have lingering effects into the next.

Among the topical fields, specialists in environmental history and the history of sexuality have the youngest demographic profile, as almost 70 percent of the employed faculty members in those fields earned their highest degrees since 1994 (as compared to 47 percent of all listed faculty in the Directory). Conversely, only about 30 percent of the employed faculty specializing in diplomatic, economic, and intellectual history earned their degrees after 1994.

Among the geographic specialties, European and US history have the oldest demographic profiles, as 41 and 46 percent, respectively, of the specialists in each field earned their highest degrees after 1989 (and more than 13 percent earned their degrees before 1970). In contrast, more than 55 percent of the faculty working in the histories of African, Asian, Latin American, and the Middle East and Islamic world earned their degrees since 1989 (and less than 10 percent in every field earned their degrees before 1970).

Fields that have risen in the past two decades not only have a higher percentage of more recently minted PhDs, but also a higher proportion of historians occupying the increasingly numerous categories of non–tenure-track employment. In five topical fields—among specialists in the histories of law, politics, religion, sexuality, and science—more than 10 percent of the listed faculty were in part-time or adjunct positions. Specialists in public history had the highest percentage of contingent faculty, 15.2 percent, perhaps because some departments have hired as their public history faculty scholars whose main employment is as public historians. By comparison, among specialists in diplomatic, economic, and intellectual history, around 5.5 percent of the listed faculty were employed in part-time or adjunct positions.

Among the geographic specializations, world historians have the highest percentage in part-time and adjunct positions, at 17 percent. In comparison, around 6.5 percent of the specialists in African, Asian, and Latin American history were employed in contingent faculty positions. Among the two largest fields, 8 percent of the European historians and 11.4 percent of the specialists in US history were employed in part-time or adjunct positions.

While these snapshots can provide a measure of changes in the shape of the discipline at particular points in time, they cannot explain why such changes are taking place. Likewise, the trends shown here cannot provide much in the way of guidance as to the allocation of resources in the training of future historians. At best, they can only show the ever-changing dimensions of our discipline.

Robert B. Townsend is the author of History’s Babel: Scholarship, Professionalization and the Historical Enterprise, 1880–1940. When he is not pursuing history, he oversees the Washington office of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Humanities Indicators. AHA Directory editor Liz Townsend assisted in the preparation of the data for analysis.

Note: The data used in this article will be available online, at historians.org/perspectives.

No comments:

Post a Comment