CHRISTOPHER CLAUSEN, wilsonquarterly.com

As the Civil War Sesquicentennial approaches cruising speed, North and South look a great deal more alike than they did on the eve of the war’s last great anniversary just 50 years ago. That much-heralded celebration coincided with the rise of the civil rights movement with a precision that was almost too good to be true. A century after Gettysburg, President John F. Kennedy had just proposed the bill that would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964. When the centennial of Appomattox rolled around, Congress was about to pass the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and few people were paying much attention to ceremonies on old battlefields.

The fact that the White House is now occupied by a man born during the Civil War Centennial to a mother from Kansas and a father from Kenya represents a historical development hardly imaginable at the time, yet all but the most regressive now accept it as perfectly natural. The major civil rights laws of the 1960s are so well established that whatever disagreements may arise in their application, few Americans understand—or can even imagine—what life was like without them. Sometimes progress takes the form of historical amnesia.

Yet the question of what the Civil War was about, and therefore what was actually won and lost, is less settled than you might expect after 150 years. Both sides fought with determination, but their motives were shifting and sometimes ambiguous. To add to the confusion, as soon as conflict ended, the losing party readjusted its position sufficiently to win back in peacetime not only a more positive historical reputation, but some very tangible benefits.

The major civil rights laws of the 1960s are so well established that whatever disagreements may arise in their application, few Americans understand—or can even imagine—what life was like without them. Sometimes progress takes the form of historical amnesia.

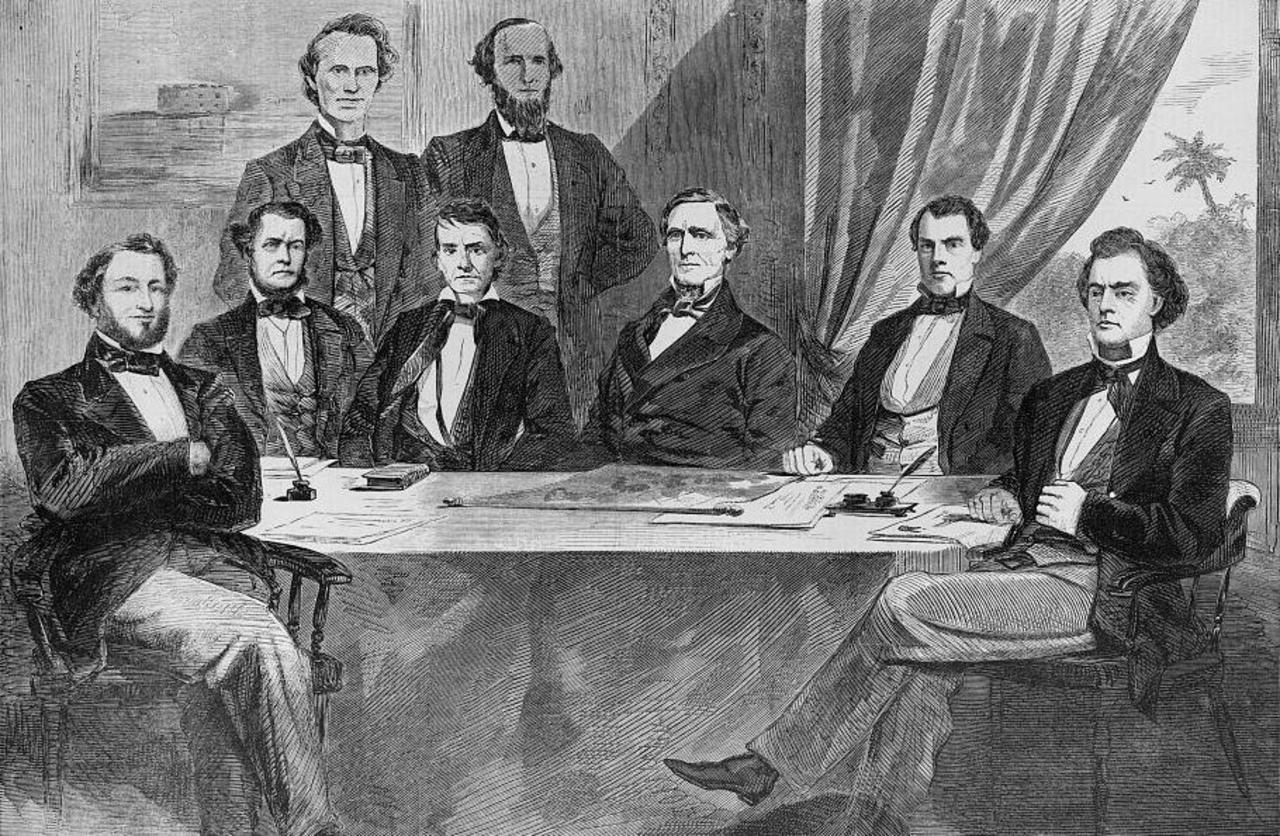

When Jefferson Davis of Mississippi resigned from the U.S. Senate after his state left the Union—the second to do so, after South Carolina seceded on December 20, 1860—he made a much-praised speech explaining his reasons. The essence of it was simple: “We but tread in the paths of our fathers when we proclaim our independence . . . not in hostility to others, not to injure any section of the country, not even for our own pecuniary benefit, but from the high and solemn motive of defending and protecting the rights we inherited, and which it is our duty to transmit unshorn to our children.” Defenders of the South since the war have taken much the same position. The 11 states that briefly constituted the Confederacy left the Union, they have said, for much the same reason the original 13 colonies left the British Empire. They fought to protect what they considered inalienable rights.

Not only did most secessionists believe in the constitutionality of their actions, the Pulitzer Prize–winning historian James M. McPherson has argued; they did indeed represent “traditional rights and views” about the relationship between the states and central government, views about which the North had largely changed its mind since the adoption of the Constitution. That is not to say that slavery was not the fundamental issue, in McPherson’s view; it was indeed slavery, he asserts, that made the North-South division deep and irreconcilable. The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, along with a Republican Congress hostile to the interests of the South, led those who favored secession—an overwhelming majority of white Southerners, McPherson concludes—to feel that the North had violated the compact embodied by the Union. Secession amounted to a preemptive counterrevolution against the Republicans’ revolution.

Whether or not they owned slaves, Southerners almost universally professed the doctrine known then and now as states’ rights, grounded in the federal system as originally understood, at least by the followers of Thomas Jefferson. When the South lost, states’ rights lost with it, and the unquestionable supremacy of the central government has been with us ever since. That abstract phrase “states’ rights” as used before the Civil War immediately prompts the question, states’ rights to what? “The right to own slaves,” McPherson explains, “the right to take this property into the territories; freedom from the coercive powers of a centralized government.”

Not only did most secessionists believe in the constitutionality of their actions, the Pulitzer Prize–winning historian James M. McPherson has argued; they did indeed represent “traditional rights and views” about the relationship between the states and central government, views about which the North had largely changed its mind since the adoption of the Constitution.

There is, of course, no logical connection between local autonomy and racial oppression. Insofar as they coincided in this instance, it was an accident of history, as some perceptive contemporaries recognized. Bound up with the defense of an odious institution to which the South had committed itself in word and deed were some positive values—the federal system, limited government, the defense of one’s homeland against long odds—that many Americans in both the North and the South would continue to profess. Lord Acton, the English apostle of liberty, strongly supported the Confederacy while loathing slavery. “History,” he explained, “does not work with bottled essences, but with active combinations.” Acton defended his position by arguing that a federal structure like the American one, whose balance of central and local powers he felt the North was destroying, would be the best means for a future united Europe to avoid the dangers of nationalism. He was a man in some ways clearly ahead of his time.

For the seven states that seceded first, however, distinguishing between slavery and states’ rights was a waste of breath. These were the Cotton States, and four of them—South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, and Texas—issued mini-declarations of independence explaining what possessed them to end a union that had begun in revolution 85 years earlier. Fortunately for the Confederacy, whose success depended in large part on achieving recognition and assistance from antislavery Europe, these declarations, with their tedious legalisms and tendentious histories of the slavery controversy in American politics, went largely unread. South Carolina complained that Northerners had systematically shirked their constitutional obligation to return escaped slaves and were now inciting “servile insurrection.” Texas made similar claims in pseudo-Jeffersonian language, adding for good measure that the federal government had failed to protect white Texans from raids by hostile Indians and Mexican “banditti.” In a rare lapidary sentence, Jefferson Davis’s Mississippi candidly proclaimed: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world.”

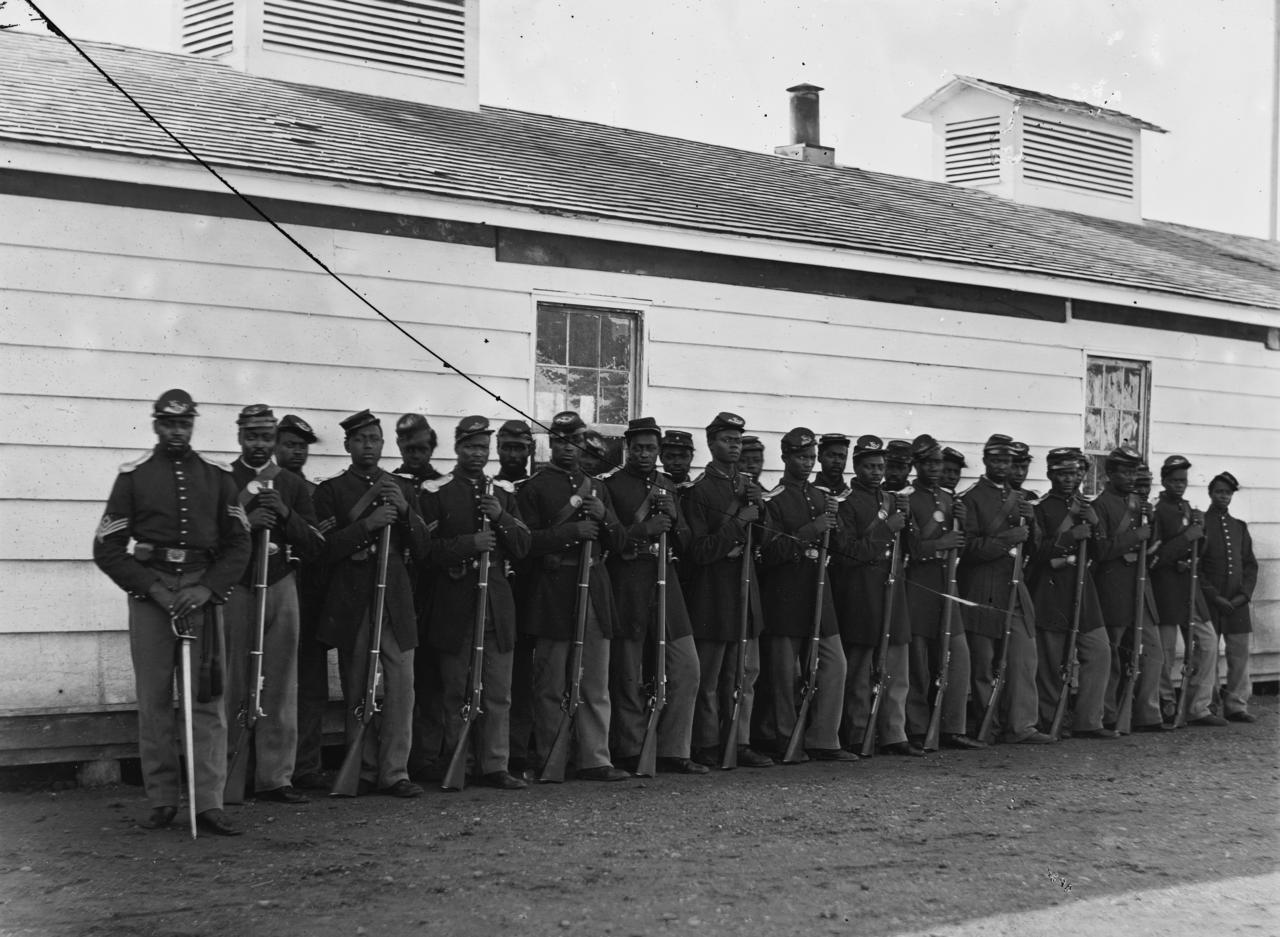

Because slavery is one feature of the American past that long ago lost all its defenders, explaining the war solely in these terms almost requires portraying it as a conflict of good against evil. Many academic historians who fervently support diplomatic compromise and peace processes in today’s world largely endorse the Lincoln administration’s refusal of those means in the 1860s and its determination to prevail unconditionally, no matter what the scale of death and devastation. This shift in the interpretations of historians became dominant after the civil rights movement and can be seen even in the titles of major works, as the Mississippi novelist Shelby Foote’s evenhanded The Civil War: A Narrative(1958–1974) was soon challenged by McPherson’s more militant Battle Cry of Freedom (1988). The Lincoln administration’s gradual transition from reluctant prosecutor of a war undertaken merely to save the Union to the Emancipation Proclamation and, by 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment, is one of the familiar legends of American history.

Less familiar is the postbellum change of emphasis by Southern writers in their depiction of the motives behind the Confederate cause, from the defense of slavery to the more abstract and sympathetic protection of limited government, states’ rights, and the freedom of a local majority to decide its own political destiny. Identifying their new nation inextricably with slavery made foreign support more difficult to attract, especially once the North decided it was explicitly fighting for emancipation. By the same token, once defeat came, Southerners who wished to save something from the ruins needed to redefine their reasons for resisting so valiantly. This necessity applied not only to the historical record, but also to their immediate political needs in grappling with Reconstruction.

Edward A. Pollard, a Richmond newspaper editor, began writing a history of the war almost as soon as it began and published several installments while it was still going on. In explaining secession to Southern readers in 1862, he recounted at length the controversy over slavery from its beginnings through the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the Compromise of 1850, and Bleeding Kansas down to what he saw as the North’s treachery in embracing Hinton Rowan Helper’s antislavery tract The Impending Crisis of the South (1857) and John Brown’s effort to start a slave rebellion with his raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859. Treachery was, Pollard maintained, the basis of nearly all Northern politics, and was demonstrated even by those Northerners who seemed to share Southern convictions about the scope of federal power: “While acting with the South on empty or accidental issues,” he complained, “the ‘State Rights’ men of the North were, for all practical purposes, the faithful allies of the open and avowed consolidationists on the question that most seriously divided the country—that of negro slavery.” Sneering at the successive compromises that had averted war for so long, Pollard praised the militancy of South Carolina and ended his account of the war’s background with a portentous description of the state of affairs on the day of Lincoln’s inauguration: “Abolitionism and Fanaticism had not yet lapped blood. But reflecting men saw that the peace was deceitful and temporizing; that the temper of the North was impatient and dark; and that, if all history was not a lie, the first incident of bloodshed would be the prelude to a war of monstrous proportions.”

When Pollard published a complete version of his history for a national audience in 1866 under the title The Lost Cause, his account of the war’s background underwent considerable alteration. Although “a political North and a political South” were already recognized when the Constitution was adopted, slavery was not really the issue. “The slavery question is not to be taken as an independent controversy in American politics. It was not a moral dispute. It was the mere incident of a sectional animosity”—that is, a pretext for the North’s jealousy of the South’s greater power in the early Republic.

While protesting that Southern slavery “was really the mildest in the world,” Pollard declared tactfully that “we shall not enter upon the discussion of the moral question of slavery.” As an institution, it was gone forever; defending it now would simply prejudice Northern readers further against the South. Instead, he repeated, “the slavery question was not a moral one in the North, unless, perhaps, with a few thousand persons of disordered conscience. It was significant only of a contest for political power, and afforded nothing more than a convenient ground of dispute between two parties, who represented not two moral theories, but hostile sections and opposite civilizations.” Needless to say, Southern civilization in Pollard’s eyes was more elevated and honorable than that of the “coarse and materialistic” North.

Pollard’s immensely popular book quickly became the standard Southern history of the war, a status it retained for decades in part because it made slavery a side issue in a war that was really fought by the South for states’ legitimate rights and by the North for sheer power. This position, still popular among Southern commemorative organizations and Confederate reenactors, made possible the abiding romantic image of the Lost Cause. It was not made up entirely out of whole cloth. As a Virginian, Pollard had pointed out even in 1862 that the states of the upper South (Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee) chose not to secede over Lincoln’s election and left the Union only when the North began a war of coercion against their departed sisters. Since Virginia was the most important Southern state, site of more battles than any other, and home of the preeminent Confederate hero, Robert E. Lee (a man who had reluctantly followed his reluctant state out of the Union), its motives and sufferings were crucial to rehabilitating the failed Confederacy itself.

Another newspaper editor, Henry Grady of Atlanta, proved even more successful at restoring the South’s honor by retouching the historical record. “The New South,” a much-reprinted 1886 speech Grady delivered to an audience of New Englanders, stands as a completed monument to a civilization that had fought gallantly for eminently moral reasons, lost through no fault of its own, and was now starting anew better than ever—a region of honorable gentlemen and pure ladies whom any nation would be proud to embrace as fellow citizens. After paying graphic tribute to the poor “hero in gray with a heart of gold” returning from Appomattox to a devastated homeland, he turned to the demise of slavery: “The South found her jewel in the toad’s head of defeat. The shackles that had held her in narrow limitations fell forever when the shackles of the Negro slave were broken. Under the old regime, the Negroes were slaves to the South, the South was a slave to the system.” Without slavery, the South was far better off than it had been before the war. “The New South,” Grady announced, “presents a perfect democracy,” in which former masters and former slaves alike would experience “the light of a grander day.” It was an age of florid oratory.

When he spoke of the war itself, Grady, whose father had died for the Confederacy, was less conciliatory. “The South has nothing for which to apologize. She believes that the late struggle between the States was war and not rebellion, revolution and not conspiracy, and that her convictions were as honest as yours. I should be unjust to the dauntless spirit of the South and to my own convictions if I did not make this plain in this presence. The South has nothing to take back.” For Grady and his enthusiastic audiences, the outcome of the war spoke for itself, and his assurance that the New South fully accepted reunion and emancipation left no fundamental issues unresolved. As Shelby Foote described the beginnings of postwar harmony, “the victors acknowledged that the Confederates had fought bravely for a cause they believed was just and the losers agreed it was probably best for all concerned that the Union had been preserved.”

After 1865, then, Southern apologists hardly ever claimed that the country or the region would have been better off had slavery survived. States’ rights, of course, was another matter. A decade before Grady put the final rhetorical seal on it, the subtle alteration in the Southern position had encouraged Northerners to revert to what might be called “default federalism,” a more traditional understanding of the constitutional system modified only by the conclusion that slavery and secession had been settled for all time. Fifteen years after Fort Sumter, ordinary citizens in the North and their political leaders were looking for an exit strategy from a devastated, occupied, but still defiant South in the throes of the bitterly hated Reconstruction. The outcome of the 1876 presidential election was disputed amid massive fraud, and a commission ultimately had to settle it. The eventual result was a bargain that historians today, following C. Vann Woodward’s classic Reunion and Reaction (1951), uniformly denounce as the shameful beginning of an era of segregation and white supremacy that lasted until the middle of the 20th century.

The South agreed, in effect, to allow the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, to take office. The new president and congressional leadership agreed in turn to withdraw the last occupation troops from the South and let the vanquished run their ruined states according to their own prejudices. Broadly speaking, state governments were free to pass any laws that did not overtly challenge the authority of the federal government or outrage the elastic conscience of a national majority. So long as they made no attempt to secede or reinstitute slavery, white Southerners were free to build monuments to the Confederate soldier in every county seat, romanticize the Lost Cause to their hearts’ content, and deny the rights of citizenship to anyone with a visible fraction of African DNA.

This agreement, sometimes referred to as the Compromise of 1877, finally ended the Civil War, though at a heavy cost. That it sold out the recently freed slaves is beyond question. So, unfortunately, is the fact that a deal of this sort was unavoidable. If you force the inhabitants of 11 states to remain part of your country after defeating them in a conflict that took 600,000 lives, but shrink from ruling them indefinitely by martial law, you have to compromise sooner or later in ways that may distress future generations. As Woodward expressed it in a 1958 speech at Gettysburg College, the North had fought the war and imposed Reconstruction for three reasons: to save the Union, to abolish slavery, and, more equivocally, to bring about racial equality. The first two aims were achieved and soon accepted, however grudgingly, by the South. The third, seemingly assured by constitutional amendments and supporting legislation, was bargained away for most of another century.

“It would be an ironic, not to say tragic, coincidence,” Woodward wrote on the eve of the Centennial, “if the celebration of the anniversary took place in the midst of a crisis reminiscent of the one celebrated.” Now that that second crisis too is a matter of history, its timing a hundred years after secession seems nearly inevitable. By that time Southerners and Northerners had fought on the same side in two world wars, and the solidity of the Union was beyond question. The rusty, clanking apparatus of institutionalized inequality had finally become such a widely recognized contradiction to official American values, highlighted both by our Cold War adversary’s propaganda and our own television news broadcasts, that the days of the post–Civil War compromise were clearly numbered. Without ever fully agreeing on the rights and wrongs of the war itself, the nation at last attended to its most ignominious legacy—the hard bargain through which reunification had been accomplished.

* * *

Christopher Clausen, the author of Faded Mosaic (2000) and other books, writes frequently about the Civil War and historical memory.

No comments:

Post a Comment