The below from

E PLURIBUS UNUM

Origin and Meaning of the Motto

Carried by the American Bald Eagle

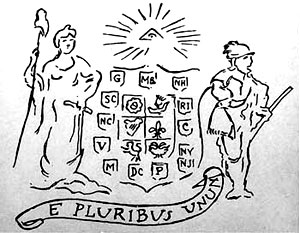

E pluribus unum is the motto [today considered unofficial - JB] suggested by the committee Congress appointed on July 4, 1776 to design "a seal for the United States of America." The below sketch of their design accompanied a detailed description of their idea for the new nation's official emblem.

A motto's purpose is to express the theme of a seal's imagery – especially that of the shield.

A motto's purpose is to express the theme of a seal's imagery – especially that of the shield.

The center section of this shield has six symbols for "the Countries from which these States have been peopled": the rose (England), thistle (Scotland), harp (Ireland), fleur-de-lis (France), lion (Holland), and an imperial two-headed eagle (Germany).

Linked together around the shield are 13 smaller shields, each with the initials for one of the "thirteen independent States of America."

On August 20, 1776, this first committee submitted their Great Seal design to Congress (including Benjamin Franklin's idea for the reverse side).

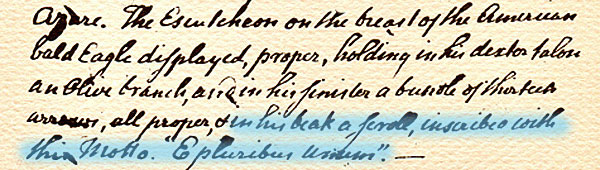

Although their design was not approved (and two more committees would be appointed), their motto E Pluribus Unum was selected by Charles Thomson in 1782 when he created the final Great Seal whose centerpiece is the American bald Eagle:

in his beak a scroll, inscribed with this Motto. "E pluribus unum".

Thomson explained that the motto E pluribus unum alludes to the union between the states and federal government, as symbolized by the shield on the eagle's breast. The thirteen stripes "represent the several states all joined in one solid compact entire, supporting a Chief, which unites the whole and represents Congress."

Translating E PLURIBUS UNUM Pluribus is related to the English word: "plural." Unum is related to the English word: "unit."

The meaning of this motto is better understood

when seen with the image that originally accompanied it:

Discover the Source of E Pluribus Unum,

the message carried by the American Bald Eagle. |

Source of E PLURIBUS UNUM

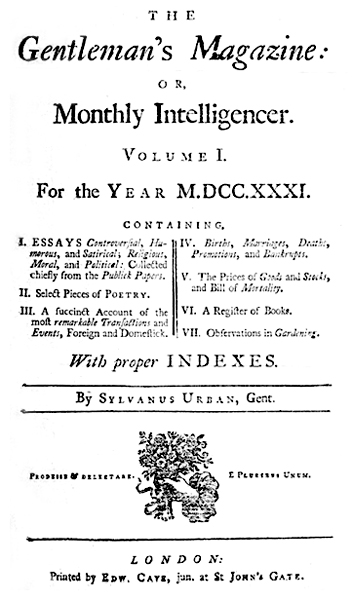

The Latin motto "E Pluribus Unum" appeared on the title page of the annual volume of the Gentleman's Magazine or Monthly Intelligencer – next to a drawing of a hand holding a bouquet of different flowers.

The Gentleman's Magazine had been published monthly in London since 1731 and was well known to literate Americans in the 1770s. The annual volume with "E Pluribus Unum" at the bottom of its title page brought together the magazine's twelve editions from that year. It provided readers with lots of useful information.

From:

"Just a month after the completion of the Declaration of Independence, at a time when the delegates might have been expected to occupy themselves with more pressing concerns—like how they were going to win the war and escape hanging—Congress quite extraordinarily found time to debate the business of a motto for the new nation. (Their choice, E Pluribus Unum, ‘One from Many,' was taken from, of all places, a recipe for salad in an early poem by Virgil.)"

Detail of the "Apotheosis of Washington" fresco on the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol

In the 1770s, symbols of unity were common on the money. See emblems on Continental Currency that inspired and reflected E pluribus unum.

The below from

Motto Mania

Religious Right Allies In The House Rally For ‘In God We Trust’

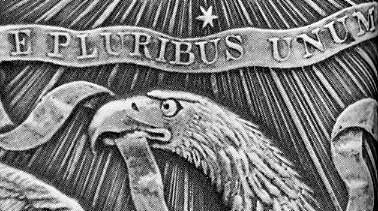

Approved by the Continental Congress in 1782, the Great Seal of the United States is an impressive symbol. You can see it on the back of a dollar bill. Pay special attention to the ribbon in the eagle’s beak. It reads, “E Pluribus Unum” – Latin for “Out of Many, One.”

This noble phrase is especially apt for the United States, a nation of immigrants consisting of people of many backgrounds, nationalities and perspectives about religion.

For many years, “E Pluribus Unum” served as our nation’s unofficial motto. In 1956, Congress decided to create an official motto and bypassed the old phrase. They went instead with “In God We Trust.” (Remember, this was during the Cold War, when we were fighting “Godless Communism.”)

The use of “In God We Trust” on coins and paper money has occasionally been challenged in court by non-theistic groups. These legal challenges have not been successful, and there the matter rests.

Last month, the U.S. House of Representatives decided to reaffirm the use of “In God We Trust” as the national motto and encourage its display in public schools and other public buildings. The result was a foregone conclusion, akin to asking members of Congress if they like motherhood and baseball. The measure passed 396-9.

What was the point of all of this? The measure’s sponsor, U.S. Rep. Randy Forbes (R-Va.), an ally of the Religious Right, insisted that “In God We Trust” is under threat. But Forbes was unable to pinpoint any specific examples.

In fact, this vote was just shameless political posturing. It was another effort to reignite the “culture wars” in advance of the 2012 elections. It’s disgraceful that the very people who claim to treasure the motto so much aren’t above using it to score cheap political points.

A handful of members had the courage to vote “no.” U.S. Rep. Bobby Scott (D-Va.) recited a litany of problems facing the country and lamented that “we are debating whether or not to affirm and proliferate a motto that was adopted in 1956 and is under no threat of attack. In addition to diverting attention away from substantive issues, the resolution is unconstitutional.”

U.S. Rep. Justin Amash (R-Mich.), the only Republican to vote “no,” issued an insightful statement: “The fear that unless ‘In God We Trust’ is displayed throughout the government, Americans will somehow lose their faith in God, is a dim view of the profound religious convictions many citizens have.”

In poll after poll, the American people have said they want congressional action on jobs and the economy. Instead, they are getting attempts to appease the Religious Right by fanning the flames of the culture war.

Maybe this tells us something about why Congress has an approval rating that currently hovers at about 9 percent.

1 comment:

What is the name of the top picture with the angel, shield and eagle

Post a Comment