Alia E. Dastagir, USA TODAY

uncaptioned image from article

Analysis: In an America deeply divided, hate incidents appear to be increasing and growing more brutal.

It feels like nearly every week, America is rattled by a new incident of hate.

In June, a white man in a Chicago Starbucks was filmed calling a black man a slave, and a white woman in a New Jersey Sears was videotaped making bigoted comments against a family she believed was Indian (they were not). In May, two men on a Portland train were stabbed to death trying to stop a white supremacist's anti-Muslim tirade against two teenagers.

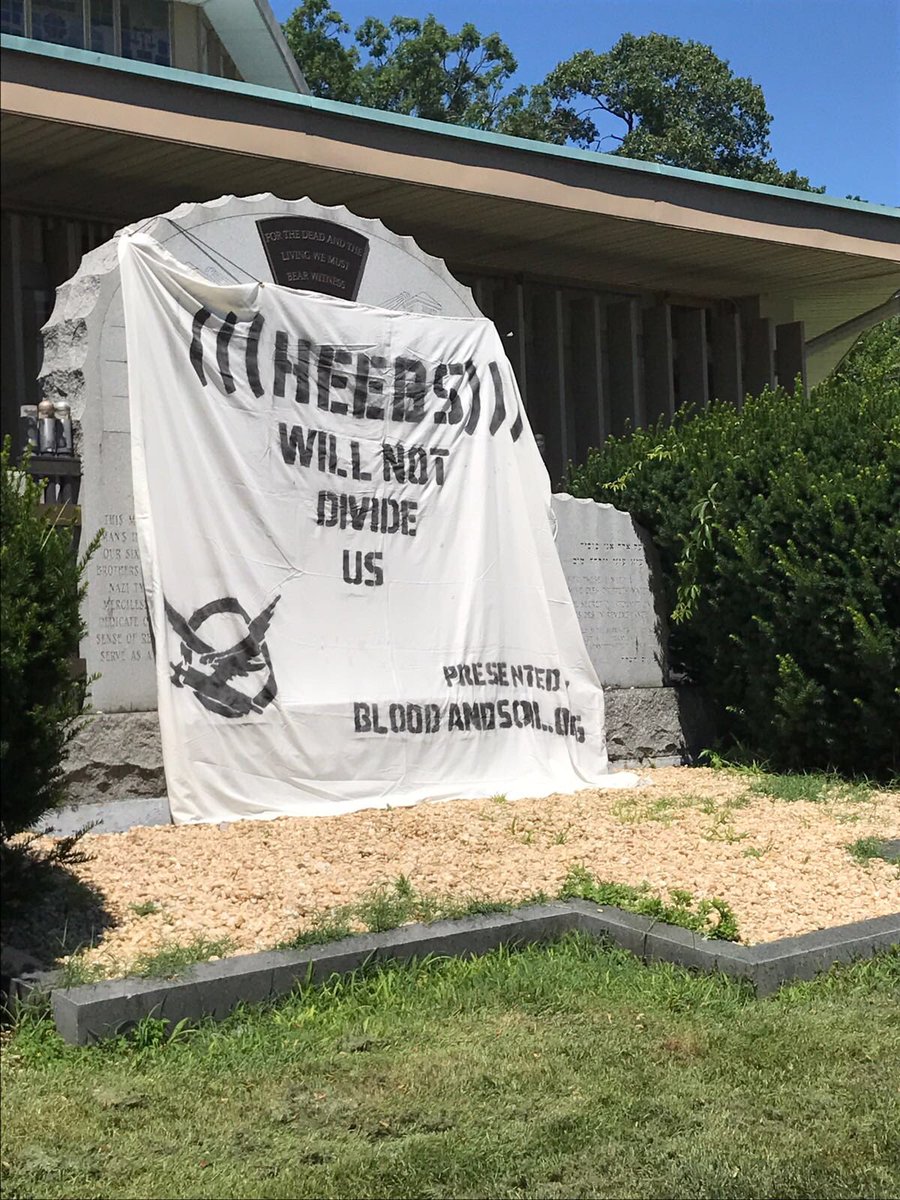

Hate symbols are showing up around the country: nooses in the nation's capital, racist graffiti on the front gate of LeBron James' Los Angeles home, a banner with an anti-Semitic slur over a Holocaust memorial in Lakewood, N.J. On Saturday, the Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan rallied in Charlottesville, Va., less than two months after white supremacist Richard Spencer — who coined the term "alt-right" — led a similar protest in the city against the removal of a Confederate monument. Several white nationalist groups are planning another rally for Aug. 12.

In an America where deep divisions exposed in the presidential election have only intensified in the past eight months, these incidents take on new meaning as they become more widespread.

"They're increasing not only in number but in terms of their ferocity," said Chip Berlet, a scholar of the far right.

Groups that track these incidents — including the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and the non-profit news organization ProPublica, which is creating a national database of hate crimes and bias — say hate incidents are a national problem whose scope we don't fully grasp. Tracking them is notoriously difficult:

- Not all law enforcement agencies send hate crime data to the FBI.

- Five states don't have any hate crime protections.

- Many states don't include protections for LGBTQ people.

- Incidents of public harassment motivated by hate bias may not meet the legal definition of a "hate crime."

While a patchwork of data means we don't have a complete picture of the problem, the SPLC and the ADL say available numbers show disturbing trends. In its most recent hate crimes report, the FBI tracked a total of 5,818 hate crimes in 2015, a rise of about 6.5% from the previous year, and showed that attacks against Muslims surged. The SPLC documented an uptick of hate and bias incidents after the presidential election, tracking 1,094 in the first month alone. The organization also says the number of hate groups in the U.S. increased for a second year in a row in 2016. In April, the ADL reported anti-Semitic incidents in the U.S. rose 86% in the first quarter of 2017.

"Even though the data is incomplete, we still think it's statistically significant, and in that it's troubling to see more manifestations of prejudice than we've seen in the past," said Jonathan Greenblatt, the CEO of the ADL.

Minorities feel less safe

By 2055, the U.S. will not have a single racial or ethnic majority, a change driven by immigration, according to the Pew Research Center. An analysis conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute and The Atlantic — based on surveys taken before and after the election — reveals that members of the white working class concerned about immigration were more than 3.5 times more likely to vote for President Trump. Nearly half of white working-class Americans said, “things have changed so much that I often feel like a stranger in my own country.”

Heidi Beirich, leader of the SPLC's Intelligence Project — which publishes the organization's Hatewatch blog — said right now minorities feel less safe, particularly Muslim and immigrant communities. According to the Pew Research Center, 41% of Hispanics say they have serious concerns about their place in America since the presidential election.

"People feel like they could be attacked at any moment," she said. "Often, they also don’t trust the police to help them."

While the FBI's data typically show 5,000 to 6,000 hate crimes a year, the Department of Justice's estimates are much higher. A report out this month from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, based on data from the National Crime Victimization Survey, show Americans experienced an average of 250,000 hate crime victimizations each year from 2004 to 2015. About a quarter of hate crime victims who didn't report said they feared police wouldn't be able to help them.

Us vs. Them

For years before he ran for president, Trump roused the “birther” movement that falsely questioned the legitimacy of Barack Obama, the nation’s first black president. During the presidential campaign, Trump said an Indiana-born federal judge was biased because of his "Mexican heritage." Since becoming president, Trump has taken a hard stance on immigration, instituting a travel ban on immigrants from six Muslim-majority countries, which the Supreme Court partially reinstated in late June.

Trump's ascendance, Berlet said, was built upon a narrative of "us vs. them," language that resonates with many Americans who fear cultural shifts brought on by changing demographics.

After the deadly shooting at Pulse nightclub in June 2016, then-candidate Trump said, "The Muslims have to work with us. They have to work with us. They know what's going on. They know that he was bad. They knew the people in San Bernardino were bad. But you know what? They didn't turn them in. And we had death and destruction."

"When a public figure with a high status identifies a group that is described as threatening to the stability of the community or the nation, in certain conditions this can lead people to conclude that they have to defend their way of life from these 'others,'" Berlet said. "These scapegoated or demonized others have to be either silenced or eradicated."

Trump has been repeatedly asked to do more to denounce hate associated with his name. Expressions of bigotry among his supporters were well-documented during his campaign and Trump himself has been accused by civil rights groups of using hateful and violent rhetoric, as well as being too reticent in condemning it. Just this month, Trump posted a CNN smackdown clip on Twitter that was taken from a Reddit troll who the ADL says has “a consistent record of racism, anti-Semitism and bigotry."

Of the 1,094 hate and bias incidents the SPLC counted in the month after the election, 37% of them directly referenced either Trump, his campaign slogans or his remarks about sexual assault.

White House press secretary Sean Spicer has denied that such hate incidents have increased since Trump’s election victory. And many Americans who support Trump — though they admire his bluntness and tendency to eschew political correctness— say they don't condone racism or violence either.

"It doesn’t make one racist to have voted for Trump, and I’m sure many didn’t pay that much attention to the campaign," Beirich said. "That said, Trump’s rants against Mexicans, Muslims and women were widely reported. So clearly Trump’s views on these matters weren’t disqualifying for many Trump voters. For those Trump voters bothered by this racism, I hope they will speak out against it. It could help increase civility in the U.S."

A nation divided

Increased political polarization is part of what moves hate from the margins to the mainstream, Greenblatt said. Sentiments once considered extreme become validated and "people feel the pain of prejudice in a manner that is really beneath our values as a country," he said.

The Pew Research Center found about half of Democrats and Republicans say the other party makes them feel “afraid." More than 40% of Democrats and Republicans say the opposite party’s "policies are so misguided that they threaten the nation’s well-being.”

"I don't think either side of the ideological spectrum is exempt from intolerance," Greenblatt said. "Whether it's the U.S. president, or a university president ... I think we should expect our leaders to stand up and speak out against manifestations of hate."

And the rest of us? We remain where we always have, Greenblatt said, capable of moving the country away from cruelty and toward greater justice.

When the approximately 50 KKK members converged on Charlottesville this weekend to protest what Klan member James Moore called “the ongoing cultural genocide ... of white Americans," more than a thousand counterprotesters showed up to decry hate in their city. The Klan members were heavily outnumbered, chants of "white power" drowned out by "racists go home."

"I think all of us have an obligation to interrupt intolerance when it happens and to be an ally when we see others being subjected to harassment and hate," Greenblatt said. "We owe it to ourselves to make sure we call upon our better angels when we see people that we know, or don't know, who are being treated unfairly because of how they look or how they pray or who they love. Every one of us is capable of rising to that occasion."

No comments:

Post a Comment