"Chomsky does no more than touch on the issue of migration—one of today’s most complex problems. ... Perhaps his most interesting contribution in an otherwise superficial discussion is his recollection that Benjamin Franklin once warned against admitting German and Swedish immigrants to the United States because they were “swarthy” and would tarnish 'Anglo-Saxon purity.'"

On Trump's ethnic background, see http://www.dailymail.co.uk/…/Wills-millions-Americans-avail…

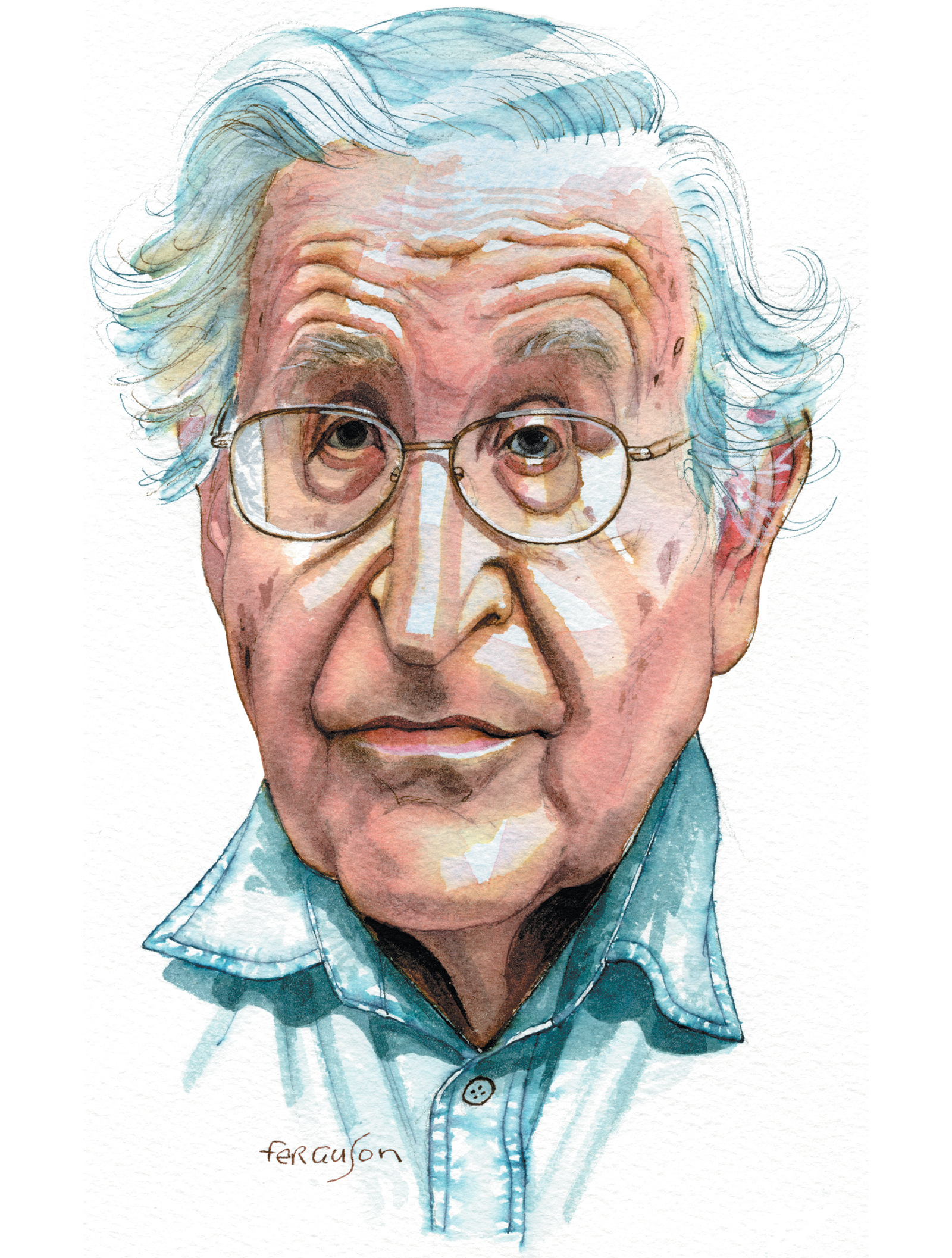

Who Rules the World?

by Noam Chomsky

Metropolitan, 307 pp., $28.00

It is hard to see yourself as others do, all the more so if you are the world’s sole remaining superpower. In unparalleled fashion, the United States today has the capacity to project its military might throughout vast parts of the globe, even if blunders in Iraq and Libya, unresolved crises in Syria and Yemen, and disturbing trends in Russia and China demonstrate the limits of American military power to shape world events. In an increasingly multipolar world, America’s power is far from its dominant heights after World War II, but it is still unmatched.

Americans tend to ease any qualms about such military supremacy with self-assurances about US benevolence. Noam Chomsky is at his best in putting those platitudes to rest, seeing an America of hypocrisy and self-interest. Yes, there are times when the United States does good, but Chomsky in his latest book, Who Rules the World?, reminds us of a long list of harms that most Americans would rather forget. His memory is almost entirely negative but it is strong and unsparing.

Chomsky reminds us that parallels to America’s tendency to act in its own interest while speaking of more global interests can be found among the powerful throughout history. As predecessors to “American exceptionalism” he cites France’s “civilizing mission” among its colonies and even imperial Japan’s vow to bring “earthly paradise” to China under its tutelage. These past slogans are now widely seen as euphemisms for exploitation and plunder, yet Americans tend to believe that their government acts in the world without similar imperial baggage.

Chomsky’s book is not an objective account of the past. It is a polemic designed to awaken Americans from complacency. America, in his view, must be reined in, and he makes the case with verve and self-confident assertion, even if factual details are sometimes selective or scarce.

Yet Who Rules the World? is also an infuriating book because it is so partisan that it leaves the reader convinced not of his insights but of the need to hear the other side. It doesn’t help that the book is a collection of previously published essays with no effort to trim the repetitive points that pop up in chapter after chapter. Nor was much attempt made to update earlier chapters in light of later events. The Iranian nuclear accord and the Paris climate deal are mentioned only toward the end of the book, even though the issues of Iran’s nuclear program and climate change appear in earlier chapters.

At times Chomsky’s book suffers from simple sloppiness. For example, he reports that “the Obama administration considered reviving military commissions” on Guantánamo when in fact these commissions have been operating there for most of President Barack Obama’s eight years in office. And in certain places it is simply confused, as when Chomsky quotes from a review by Jessica Mathews in these pages and implies that she subscribes to the view that America advances “universal principles” rather than “national interests,” when in fact she was criticizing that perspective as part of her negative review of a book by Bret Stephens.*

In some respects, Chomsky’s preoccupation with American power seems out of date because the limits of American power have become so apparent. When we ask “Who rules the world?” and take account of Syrian atrocities, the emergence of the Islamic State, or the mass displacement of refugees, the answer is less likely to be the American superpower than no one. Obama’s foreign policy has been far more about recognizing the limits of US military power than the exercise of that power, but this merits barely a mention by Chomsky. His America is the one of military adventure—the Vietnam War, the Bay of Pigs, the Central American conflicts of the 1980s, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the potentially suicidal recklessness of the nuclear arms race.

Chomsky’s selective use of history limits his persuasiveness. He blames Middle East turmoil, for example, largely on the World War I–era Sykes-Picot agreement that divided the former Ottoman Empire among British and French colonial powers. He’s right that the borders were drawn arbitrarily, and that the multiethnic and multiconfessional states they produced are difficult to govern, but is that really an adequate explanation of the region’s current turmoil? President George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq fits his thesis of American malevolence, and the terrible human costs of the war get mentioned, but Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s decision to fight his country’s civil war by targeting civilians in opposition-held areas, killing hundreds of thousands and setting off the flight of several million refugees, does not. Nor does Russia’s decision to back Assad’s murderous shredding of the Geneva Conventions, since Chomsky’s focus is America’s contribution to global suffering, not Vladimir Putin’s.

Still, it is useful to read Chomsky because he does undermine the facile if comforting myths that are often used to justify US action abroad—the distinction between, as Chomsky puts it, “what we stand for” and “what we do.” His views are held not only by American critics on the left but also by many people around the world who are more likely to think of themselves as targeted rather than protected by US military power.

For example, Americans are rightly appalled by al-Qaeda’s attacks on September 11, 2001, which killed some three thousand people, but most Americans have relegated to distant memory what Chomsky calls “the first 9/11”—September 11, 1973—when the US government backed a coup in Chile that brought to power General Augusto Pinochet, who proceeded to execute some three thousand people. As with US actions in Cuba and Vietnam, the US-endorsed overthrow of the socialist government of Chilean President Salvador Allende was meant, in the words of the Nixon administration quoted by Chomsky, to kill the “virus” before it “spread contagion” among those who didn’t want to accommodate the interests of a US-led order. The “virus,” Chomsky writes, “was the idea that there might be a parliamentary path toward some kind of socialist democracy.” He goes on:

The way to deal with such a threat was to destroy the virus and inoculate those who might be infected, typically by imposing murderous national-security states.

Thus began the US-led redirection of Latin American militaries from external defense to internal security, with the ensuing “dirty wars” and their trails of torture, execution, and forced disappearance.

A similar rationale lay behind US actions in Vietnam and the “domino theory” used to rationalize it. Among its most tragic applications was Indonesia’s slaughter in 1965 and 1966 of half a million or more alleged Communists under the guidance of then General and soon-to-be President Suharto. Chomsky describes how this “staggering mass slaughter” was greeted with “unrestrained euphoria” in Washington’s corridors of power. Suharto so successfully swept these extensive crimes under the rug that thirty years later Bill Clinton welcomed him as “our kind of guy.” Indonesia’s current president, Joko Widodo, widely known as Jokowi, has bravely taken initial steps to expose this ugly chapter of his country’s history. Obama could assist him by opening US government archives to reveal the working relationship between CIA and US embassy operatives and the Indonesian forces doing the killing.

Chomsky takes on the facile use of the label “terrorism” to describe the actions of one’s enemies but not one’s friends. Why, Chomsky asks, did the US government condemn the 1983 attack on the Marine barracks in Beirut as an act of terrorism, given that in war a military base is a legitimate military target, but not the Israeli-backed slaughter in 1982 by Lebanese Phalangists of Palestinian civilians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps? To describe any attack by one’s opponent regardless of the target as “terrorism” is to endanger ordinary civilians by blurring the important distinction established by international humanitarian law between combatants and noncombatants. The view, as Chomsky mockingly puts it, that “our terrorism, even if surely terrorism, is benign” is dangerous, since most governments and groups, even the Islamic State, believe they are acting for some conception of the good.

Chomsky criticizes the US government for discounting large-scale civilian deaths that are the foreseeable outcome of a policy even if they are not the intent of that policy. The deliberate targeting of civilians is rightfully viewed as a war crime, but what of an attacker who knows that the consequence of an attack on a military target will be substantial civilian deaths? Chomsky cites Bill Clinton’s 1998 missile attack on Sudan’s al-Shifa pharmaceutical plant, in the unjustified belief that it was producing chemical weapons, when the attack “apparently led to the deaths of tens of thousands of people” deprived of the drugs it was producing. As is often the case, Chomsky gives no substantiation for this enormous number, but the point remains. Chomsky makes a similar observation about Israel’s bombing of electrical plants in Gaza, which interrupted water supply to Palestinians and helped to cripple Gaza’s economy, and Israel’s West Bank checkpoints, which deprive Palestinians of timely access to emergency medical care.

As for promoting democracy abroad, Chomsky says that US support for it “is the province of ideologists and propagandists.” “In the real world,” he explains, “elite dislike of democracy is the norm.” Democracy is supported “only insofar as it contributes to social and economic objectives.” But what happens when the preferences of a nation’s public differ from US objectives—such as what Chomsky describes as the Arab public’s sense that Israel is a greater threat than Iran? In those cases, Chomsky argues, notwithstanding a brief flirtation with the Arab Spring, the US government tends to be amenable to dictatorships that favor warmer relations with the West:

Favored dictators must be supported as long as they can maintain control (as in the major oil states). When that is no longer possible, discard them and try to restore the old regime as fully as possible (as in…Egypt).

The epitome of this policy, according to Chomsky, was the 2006 decision to “impose harsh penalties on Palestinians for voting the wrong way” and electing Hamas in Gaza.

In the Middle East, Chomsky focuses in particular on US hypocrisy toward Israel. Washington’s attitude toward the West Bank settlements is illustrative. The Carter administration, like most of the world, recognized that the settlements violate the Fourth Geneva Convention’s prohibition on transferring an occupying power’s population to occupied territory. The US government has never repudiated that view but, since the Reagan administration, it has tended to refer to the settlements as only “a barrier to peace.” While the United States has periodically pressed Israel to stop expanding the settlements, that “pretense of opposition reached the level of farce in February 2011, when Obama vetoed a UN Security Council resolution calling for implementation of official US policy.”

Similarly, in May 2014, the United States supported jurisdiction for the International Criminal Court (ICC) in Syria (Russia and China vetoed the resolution) but only after insisting that the resolution exempt Israel from any possible liability. That is consistent with US legislation adopted under George W. Bush authorizing an invasion of the Netherlands should any American or allied suspect be brought to The Hague for trial before the ICC. It is also consistent with the Obama administration’s failed pressure on Palestine not to ratify the ICC treaty.

Chomsky has one chapter on America’s selective outrage. Americans were outraged when Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was shot down in eastern Ukraine, apparently by Russia-backed forces, killing 298 people. But who remembers when the USS Vincennes shot down Iran Air Flight 655 in 1988, killing 290 people? The Vincennes was in the Persian Gulf at the time to defend the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, then a US ally at war with Iran. In neither case is there reason to believe that the attacker knowingly targeted a civilian aircraft, but the Western response was notably different.

Chomsky cites a New York Times report that Samantha Power, US ambassador to the United Nations, “choked up as she spoke of infants who perished” in the Malaysia Airlines crash. But he notes that the commander of the Vincennes and his anti–air warfare officer were given the US Legion of Merit award for “exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding service” and for the “calm and professional atmosphere” maintained during the period of the downing. President Reagan blamed the Iranians for the tragedy. Only under the Clinton administration did the US government admit “deep regret” and pay compensation to the victims—facts that Chomsky neglects to mention.

Likewise, the US is rightfully outraged at Hamas rocket attacks on Israeli civilians but far more reticent about the large-scale destruction of civilian property and loss of civilian life caused by Israel’s bombardment of Gaza. Invocations of Hamas using human shields do not begin to account for such likely war crimes as Israel’s targeting of Hamas commanders’ family homes or its use of artillery that had wide effects in densely populated areas.

Or to cite another example: the US government rightfully expressed outrage over the murderous attack on Charlie Hebdo by Islamist extremists who killed eleven journalists. But as Chomsky points out, there was nothing comparable to the “I am Charlie” campaign when in 1999 during the war with Serbia over Kosovo,NATO deliberately sent a missile into Serbian state television and radio (RTS) headquarters, killing sixteen journalists. Even though RTS was a propaganda outlet, that did not make it a legitimate military target, yet Washington defended the attack. Chomsky introduces the concept of “living memory”—“a category carefully constructed to include their crimes against us while scrupulously excluding our crimes against them”—to explain why there was no collection of Western leaders proclaiming “We are RTS.” Even after the Charlie Hebdo attack, while France was portraying itself as a champion of free expression, it prosecuted advocacy of boycotting goods from Israel or its settlements.

While Chomsky mostly looks back in time, he does not spare Barack Obama. One of Obama’s first acts as president was to order an end to the CIA’s use of torture, yet Chomsky quotes the journalist Allan Nairn to the effect that Obama “merely repositioned” the United States to the historical norm in which torture is carried out by proxies. But Chomsky gives no evidence of torture by such proxies under Obama. Even before Bush administration lawyers contorted the meaning of the prohibition against torture in the notorious “Torture Memos,” Chomsky notes, the legal defense for the types of mental torture preferred by the Bush CIA, euphemistically called “enhanced interrogation techniques,” was foreshadowed by the Reagan administration in the form of detailed reservations about the definition of torture in the international Convention against Torture, which were endorsed by the Clinton administration at the time of ratification in 1994.

One reason often driving the US government to ignore international norms is a sense of impunity. For example, until recently, only the United States had weaponized drones, so why should the US bother to articulate and respect rules governing their use? But such technological monopolies are inevitably short-lived, and America’s many years of using drones without articulated standards are much more likely to influence how other countries behave when they too have weaponized drones than any belated effort at standard-setting.

Chomsky does nothing to contribute to what those standards might be, lapsing into denunciatory language about drone attacks being “the most extreme terrorist campaign of modern times.” He describes “assassination” in violation of “the presumption of innocence” without addressing the obvious retort—that combatants in war can be targeted—or grappling with the central question of whether US drone attacks in places like Yemen and Somalia should be considered acts of war or bound by the more restrictive standards of law enforcement.

Groups such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State certainly have no intention of abiding by international standards. Yet the Geneva Conventions deliberately impose duties regardless of an adversary’s conduct—and for good reason, because otherwise virtually any war would descend into a tit-for-tat spiral of atrocity and retaliation. US compliance with international humanitarian law is all the more important in view of America’s unique superpower status, because its actions are more visible and far-reaching.

That makes it all the more lamentable that Obama has refused to authorize prosecution of the CIA torturers or those in the Bush administration who authorized them, thus leaving torture as a policy option for the next US president facing a serious security threat, and setting a disastrous precedent for other countries. Needless to say, many other parts of the world do not accord these actions the presumption of benevolence that Americans are more willing to embrace.

How does such hypocrisy persist in US foreign policy? Chomsky provides no clear answer. He alludes to the power of commercial interests in setting Washington’s agenda. He also notes the importance of secrecy. Government secrecy, he explains, “is rarely motivated by a genuine need for security, but it definitely does serve to keep the population in the dark.” As an example, Chomsky cites the National Security Agency’s mass collection of telecommunications metadata—a deeply intrusive program in which the records of many of our most intimate contacts have been stored in government computers and kept available for official inspection. Operating with the benefit of secrecy, government officials claimed the program was needed and had stopped fifty-four terrorist plots.

Once the claim was subjected to scrutiny, it turned out that the program, at enormous costs to American taxpayers and their privacy, had identified only one supposed plot—someone who had sent $8,500 to Somalia. Two independent oversight bodies with access to classified information have found that the phone metadata program has provided no unique value in countering terrorist threats. More recently, Chomsky notes that the details of transpacific and transatlantic trade deals have been kept secret from the public but not from “the hundreds of corporate lawyers who are drawing up the detailed provisions.”

It is perhaps unfair to challenge an author for what he didn’t write rather than what he did, but given the broad question that Chomsky asks—“Who rules the world?”—I could not help noticing how little of the world he discusses. The book is about the parts of the world where America and its closest allies, such as Israel, assert military power, but Chomsky does not in this book seem interested in the parts of the world where US military power is not exercised and seemingly incapable of making much of a difference. Africa barely appears except as a source of migration—we get no sense of the deadly conflict in South Sudan, the growing turmoil in Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo, or the murderous rampage of the Islamist group Boko Haram. China is largely ignored. Russia emerges with respect to nuclear issues but little else. South Asia appears mainly as the site of Osama bin Laden’s demise.

Chomsky does no more than touch on the issue of migration—one of today’s most complex problems. Without elaboration, he attributes Mexican migration to the United States to Mexican campesinos being forced under the NAFTA agreement to compete with heavily subsidized US agribusiness. He takes no account of Central Americans fleeing drug cartels, or even of the consequences of America’s ill-fated “war on drugs.” He mentions African migration to Europe with a passing, undeveloped reference to European colonialism. Perhaps his most interesting contribution in an otherwise superficial discussion is his recollection that Benjamin Franklin once warned against admitting German and Swedish immigrants to the United States because they were “swarthy” and would tarnish “Anglo-Saxon purity.” We can hope that before long we will regard today’s rampant Islamophobia with equal ridicule.

Chomsky concludes by answering the titular question of his book with a question. Beyond asking “Who rules the world?” we should also inquire, “What principles and values rule the world?” It is easy for a superpower to deviate from Kantian principles—to avoid treating its neighbors as it would want to be treated—because it can. No external power can compel a superpower to be principled. That is the task of its citizens.

Chomsky offers little in the way of prescription. His book is mainly a critique, as if he cannot envision a positive role for America other than a negation of the harmful ones he highlights. Yet imperfect as the book is, we should understand it as a plea to end American hypocrisy, to introduce a more consistently principled dimension to American relations with the world, and, instead of assuming American benevolence, to scrutinize critically how the US government actually exercises its still-unmatched power.

- *See Jessica T. Mathews, “The Road from Westphalia,” The New York Review, March 19, 2015. ↩

No comments:

Post a Comment