Nick Penzenstadler, Brad Heath, Jessica Guynn,usatoday.com

The Russian ads, released by Democrats on the House Intelligence Committee, offer the public the first in-depth look at the attempts to divide the U.S. ahead of the 2016 election. USA TODAY

The Russian company charged with orchestrating a wide-ranging effort to meddle in the 2016 presidential election overwhelmingly focused its barrage of social media advertising on what is arguably America’s rawest political division: race.

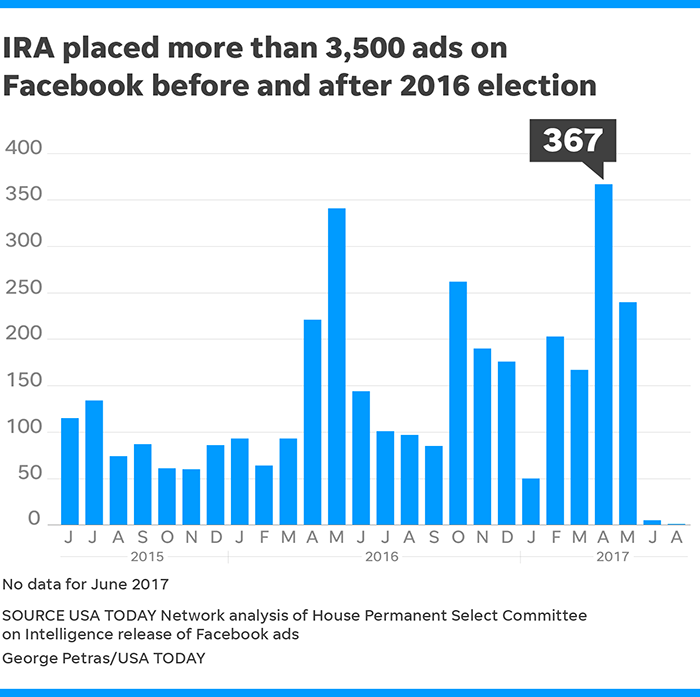

The roughly 3,500 Facebook ads were created by the Russian-based Internet Research Agency, which is at the center of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s February indictment of 13 Russians and three companies seeking to influence the election.

While some ads focused on topics as banal as business promotion or Pokémon, the company consistently promoted ads designed to inflame race-related tensions. Some dealt with race directly; others dealt with issues fraught with racial and religious baggage such as ads focused on protests over policing, the debate over a wall on the U.S. border with Mexico and relationships with the Muslim community.

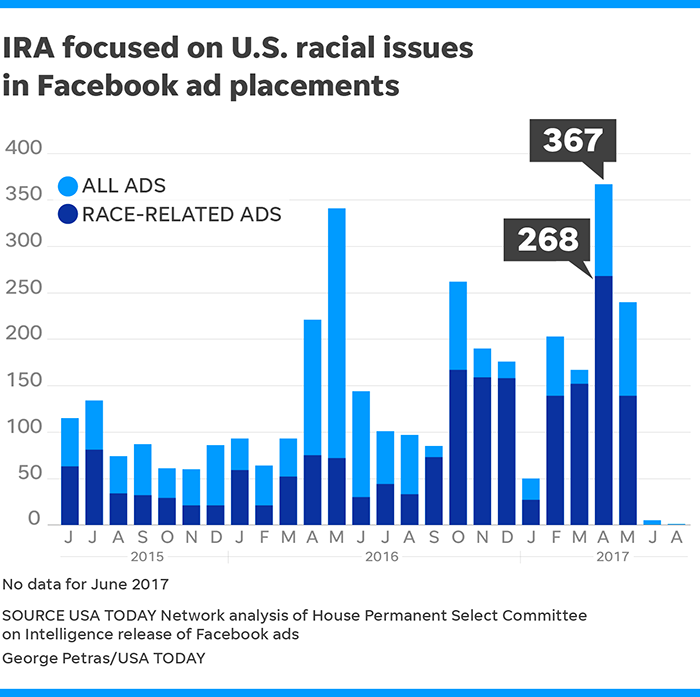

The company continued to hammer racial themes even after the election.

USA TODAY Network reporters reviewed each of the 3,517 ads, which were released to the public this week for the first time by the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. The analysis included not just the content of the ads, but also information that revealed the specific audience targeted, when the ad was posted, roughly how many views it received and how much the ad cost to post.

Among the findings:

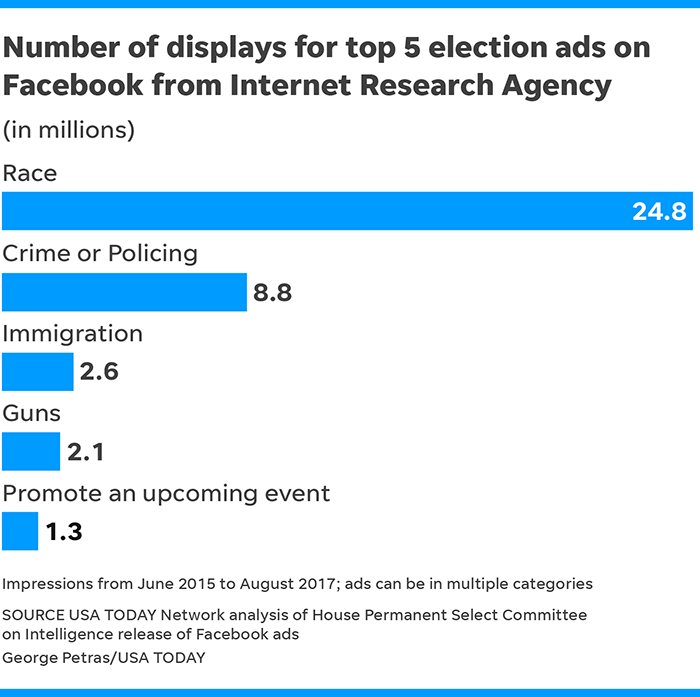

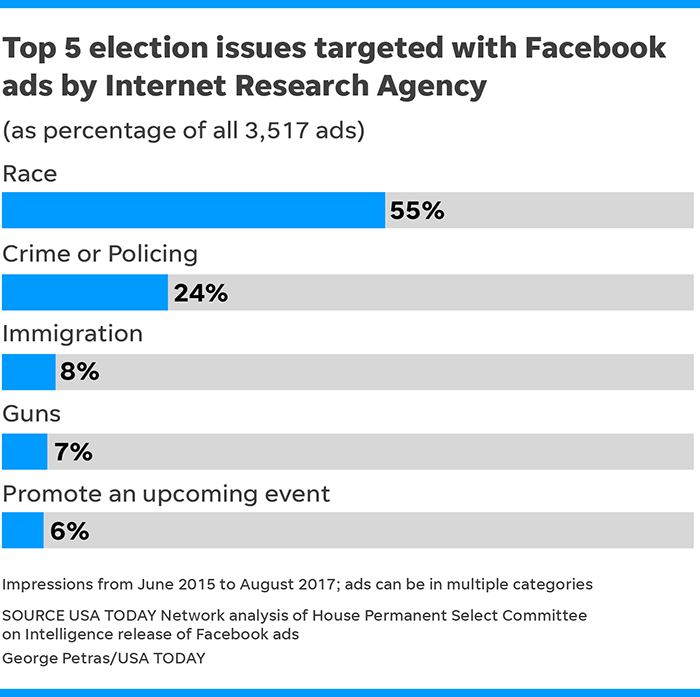

- Of the roughly 3,500 ads published this week, more than half — about 1,950 — made express references to race. Those accounted for 25 million ad impressions — a measure of how many times the spot was pulled from a server for transmission to a device.

- At least 25% of the ads centered on issues involving crime and policing, often with a racial connotation. Separate ads, launched simultaneously, would stoke suspicion about how police treat black people in one ad, while another encouraged support for pro-police groups.

- Divisive racial ad buys averaged about 44 per month from 2015 through the summer of 2016 before seeing a significant increase in the run-up to Election Day. Between September and November 2016, the number of race-related spots rose to 400. An additional 900 were posted after the November election through May 2017.

- Only about 100 of the ads overtly mentioned support for Donald Trump or opposition to Hillary Clinton. A few dozen referenced questions about the U.S. election process and voting integrity, while a handful mentioned other candidates like Bernie Sanders, Ted Cruz or Jeb Bush.

Interactive Graphic: Explaining Russia's Facebook campaign aimed at Americans

Young Mie Kim, a University of Wisconsin-Madison researcher who published some of the first scientific analysis of social media influence campaigns during the election, said the ads show that the Russians are attempting to destabilize Western Democracy by targeting extreme identity groups.

“Effective polarization can happen when you’re promoting the idea that, ‘I like my group, but I don’t like the other group’ and pushing distance between the two extreme sides,” Kim said. “And we know the Russians targeted extremes and then came back with different negative messages that might not be aimed at converting voters, but suppressing turnout and undermining the democratic process.”

Background: Special counsel indicts Russian nationals for interfering with U.S. elections and political processes

The most prominent ad — with 1.3 million impressions and 73,000 clicks — illustrates how the influence campaign was executed.

A Facebook page called “Back the Badge,” landed on Oct. 19, 2016, following a summer that saw more than 100 Black Lives Matter protests, NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s national anthem protests in August and protests over the police shootings of Terence Crutcher in Tulsa, Oklahoma and Keith Lamont Scott in North Carolina.

The information analyzed by the USA TODAY Network shows the Internet Research Agency paid 110,058 rubles, or $1,785, for the Facebook spot. It targeted 20 to 65-year-olds interested in law enforcement who had already liked pages such as “The Thin Blue,” “Police Wives Unite” and the “Officer Down Memorial Page.”

The very next day, the influence operation paid for an ad depicting two black brothers handcuffed in Colorado for “driving while black.” That ad targeted people interested in Martin Luther King Jr., Malcom X and black history. Within minutes, the Russian company targeted the same group with an ad that said “police brutality has been the most recurring issue over the last several years.”

USC professor Nick Cull, author of The Cold War and the United States Information Agency, says the ad campaign is reminiscent of tactics employed during the Soviet era. His book explored how the KGB tried to disrupt the LA Olympics by faking propaganda from the KKK threatening black athletes.

"Soviet news media always played up U.S. racism, exaggerating the levels of hatred even beyond the horrific levels of the reality in the 1950s," Cull wrote in an email. "It was one reason Eisenhower decided to move on civil rights."

Adam Schiff, the Minority Leader of the House Intelligence Committee, said he made the ads available to the public so that academics could study both the intention and breadth of the targeting.

“These ads broadly sought to pit one American against another by exploiting faults in our society or race, ethnicity, sexual orientation and other deeply cynical thoughts,” Schiff said in an interview with USA TODAY Network. “Americans should take away that the Russians perceive these divisions as vulnerabilities and to a degree can be exploited by a sophisticated campaign.”

A federal grand jury in February indicted 13 individuals accused of working for the Internet Research Agency to produce the ads. The charges related to meddling in the 2016 election, the only election interference case Mueller's office has filed so far.

The indictment included emails from the Russian company's employees that left no doubt that their objectives were “to sow discord in the U.S. political system, including the 2016 U.S. presidential election.” This effort “included supporting the presidential campaign of then-candidate Donald J. Trump and disparaging Hillary Clinton,” the indictment states.

Peter Carr, a spokesman for the special counsel, declined comment on the ads this week. An attorney for two of the companies indicted by Mueller did not respond to a request for comment. One of the companies, Concord Management and Consulting, LLC, entered a not-guilty plea on Wednesday in the U.S. District Court in D.C.

The USA TODAY Network analysis found that Russians effort first used a raft of viral memes referencing banal American pop culture, like Spongebob Squarepants and Pokémon, to apparently build support behind legitimate-looking connections before deploying the racially-tinged spots.

Hundreds of ads mixed race and policing, with many mimicking Black Lives Matter activists that melded real news events with accusations of abuse by white officers.

That type of subversion only hurts legitimate efforts to calm tensions over policing and hate crimes, said Derrick Johnson, president and CEO of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Johnson said the Russian ads likely helped to fuel “hateful, xenophobic rhetoric” throughout the 2016 presidential campaign.

“When you’re stoking fear to get a negative action directed at a targeted population based on race, and when a foreign nation uses that fear to subvert and undermine democracy, that’s become a serious problem,” Johnson said. “It’s a warning for technology companies and corporations that private citizens have entrusted with their privacy to receive factual information.”

It’s hard to measure precise impact of the campaign targeting police and their families, but it certainly didn’t help, said Jim Pasco, senior adviser to the president of the National Fraternal Order of Police, the nation’s largest police union.

"There is absolutely no doubt that these ad placements further inflamed tensions in already volatile and already sensitive situations at critical times," Pasco said.

The tech tools have changed, but the themes of disruption have not, said Bret Schafer of the German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy, which tracks activity of Russia-linked social media bots and trolls.

Social media is an effective way to target wedge issues because of the ability to micro-target ads, sending messages to confederate flag supporters at the same time as Black Lives Matter sympathizers to stoke divisions, he said.

“They are stirring up the racial pot, while then trying to connect with minority groups and saying: Look at how racist the content is online. They don’t really have to do that because the content online is racist without the Russians, to be very clear,” Schafer said.

He added that it's hard to measure how effective the campaigns were in general. Some of the ads "completely bombed," based on interactions. But stoking racial fears and tensions was often effective.

"Some of the most racist ads put out got the highest levels of engagement,” Schafer said. “It seems that when their messaging went to the extreme on some of these issues, it actually landed the hardest punch.

“If they hit 10% of the time, it's still effective for them,” Schafer said.

Contributing: Jai Agnish, The Bergen (N.J.) Record; Stacey Barchenger, Asbury (N.J.) Park Press, Natalie Alison, The Tennessean; Dave Boucher, The Tennessean; Kevin Crowe; Milwaukee Journal Sentinel; Algernon D’Ammassa, The Deming (N.M.) Headlight; Mike Ellis, Anderson Independent Mail; Stacie Galang, Ventura County Star; Greg Holman, Springfield (Mo.) News-Leader; Trevor Hughes, USA TODAY; John Kelly, USA TODAY; Ledyard King, USA TODAY; Laura Mandaro, USA TODAY; John Moses, Farmington (N.M) Daily-Times; Tovah Olsen, Lansing State Journal; Alex Ptachick, USA TODAY; Steve Reilly, USA TODAY; Todd Spangler, Detroit Free Press; Svetlana Shkolnikova, The (Bergen, N.J.) Record; Mariah Timms, (Murfreesboro, Tenn.) Daily News Journal; Elizabeth Weise, USA TODAY; Mark Wert, Cincinnati Enquirer; Dana Williams, Pacific Daily News (Guam); Anna Wolfe, Jackson (Miss.) Clarion Ledger; Amy Wu, Poughkeepsie (N.Y.) Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment