Saturday, June 30, 2018

Death on foot: America's love of SUVs is killing pedestrians

usatoday.com

Eric D. Lawrence, Nathan Bomey and Kristi Tanner, Detroit Free Press/USA TODAY NETWORKPublished 12:18 p.m. ET June 28, 2018 | Updated 3:30 p.m. ET June 29, 2018

Robert and Karen Bonta, married 50 years last summer, explored all seven continents as they charged into their 70s.

So Amy Bonta Ferin didn't worry about her parents each winter when they left their chilly Iowa home for the saguaro-dotted desert hills near Phoenix. Her mother, Ferin said, who also kept a bag packed to travel to events involving her three children and 10 grandchildren, lit up a room with her hopeful, smiling face.

"One of the hardest things to see was her in a casket," Ferin said. "She didn't have a smile on her face."

Robert and Karen Bonta, 72 and 71 respectively, were killed after an SUV struck them March 13 in the desert community of Fountain Hills, Arizona.

A Ford Explorer driven by 27-year-old Alex Bradshaw hopped a curb and hit them as they stood on a sidewalk. Canadians Patti Lou and Ronald Doornbos, were also struck by the SUV as they walked toward the corner in a marked crosswalk. Patti Lou, 60, died immediately; Ronald died June 12.

The four deaths highlight a growing danger for America’s most vulnerable road users: Death by SUV.

The four deaths highlight a growing danger for America’s most vulnerable road users: Death by SUV.

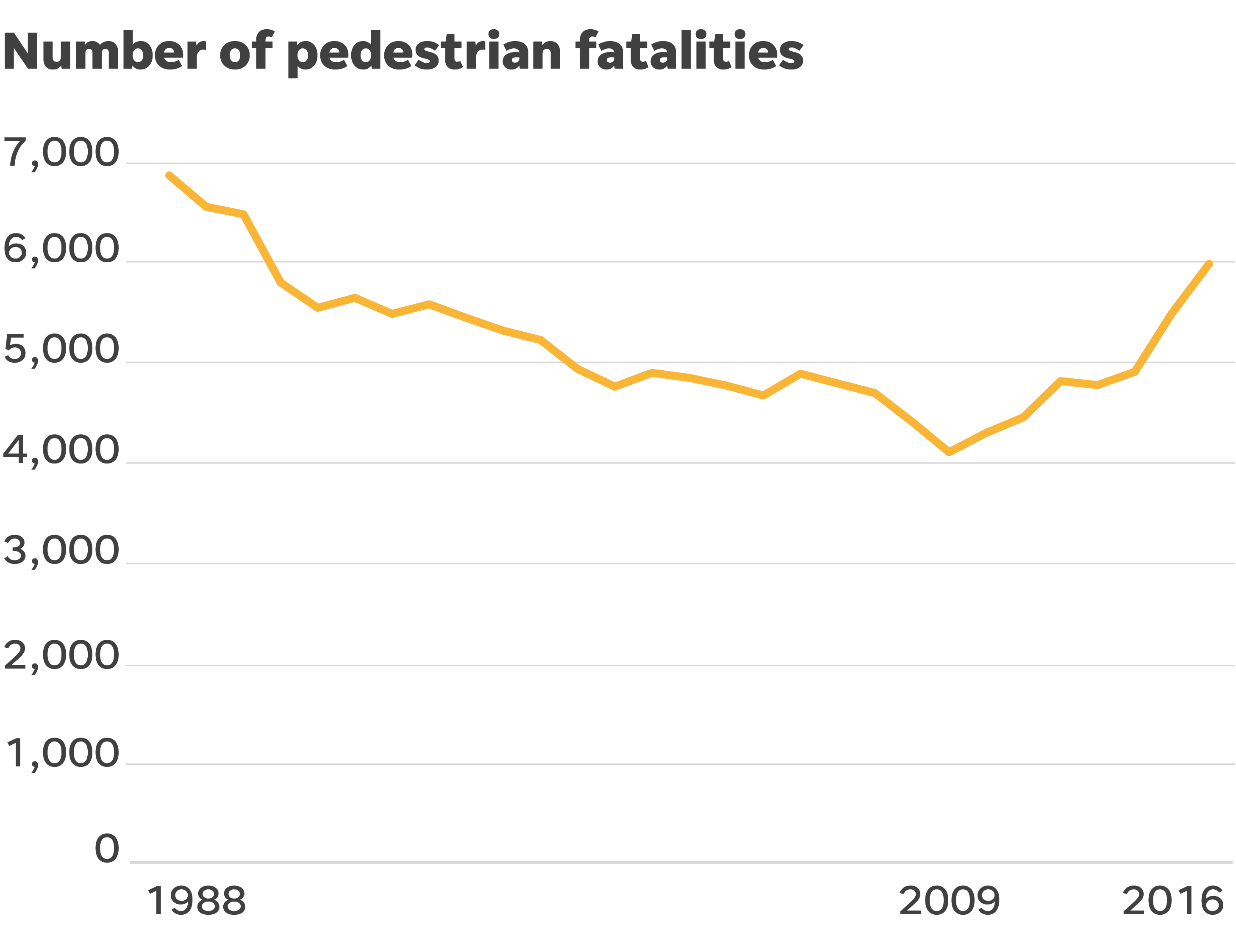

A Detroit Free Press/USA TODAY NETWORK investigation found that theSUV revolution is a key, leading cause of escalating pedestrian deaths nationwide, which are up 46 percent since 2009.

Almost 6,000 pedestrians died on or along U.S. roads in 2016 alone — nearly as many Americans as have died in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2002. Data analyses by the Free Press/USA TODAY and others show that SUVs are the constant in the increase and account for a steadily growing proportion of deaths.

Our investigation found:

- Federal safety regulators have known for years that SUVs, with their higher front-end profile, are at least twice as likely as cars to kill the walkers, joggers and children they hit, yet have done little to reduce deaths or publicize the danger.

- A federal proposal to factor pedestrians into vehicle safety ratings has stalled, with opposition from some automakers.

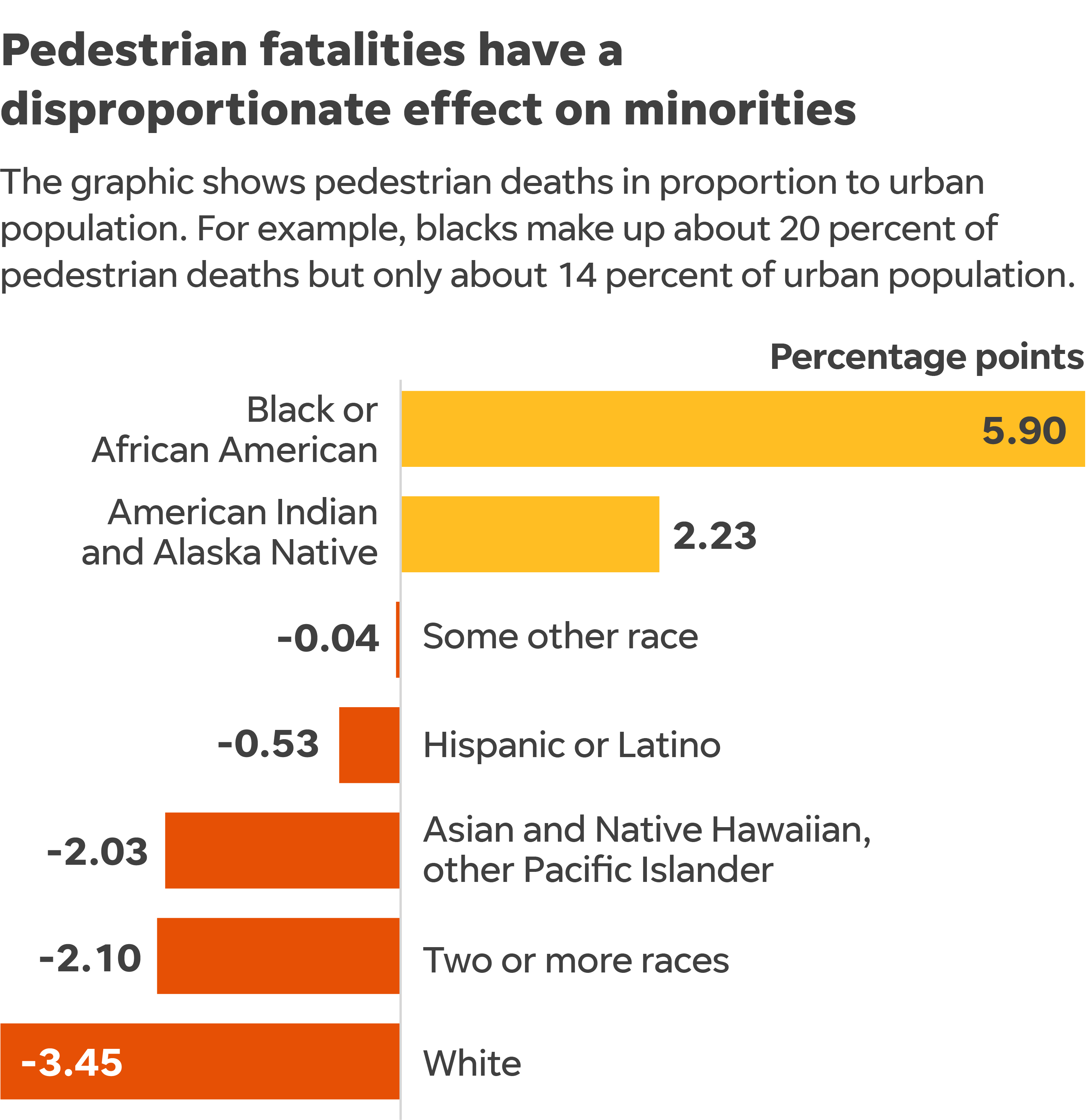

- The rising tide of pedestrian deaths is primarily an urban plague that kills minorities at a disproportionate rate.

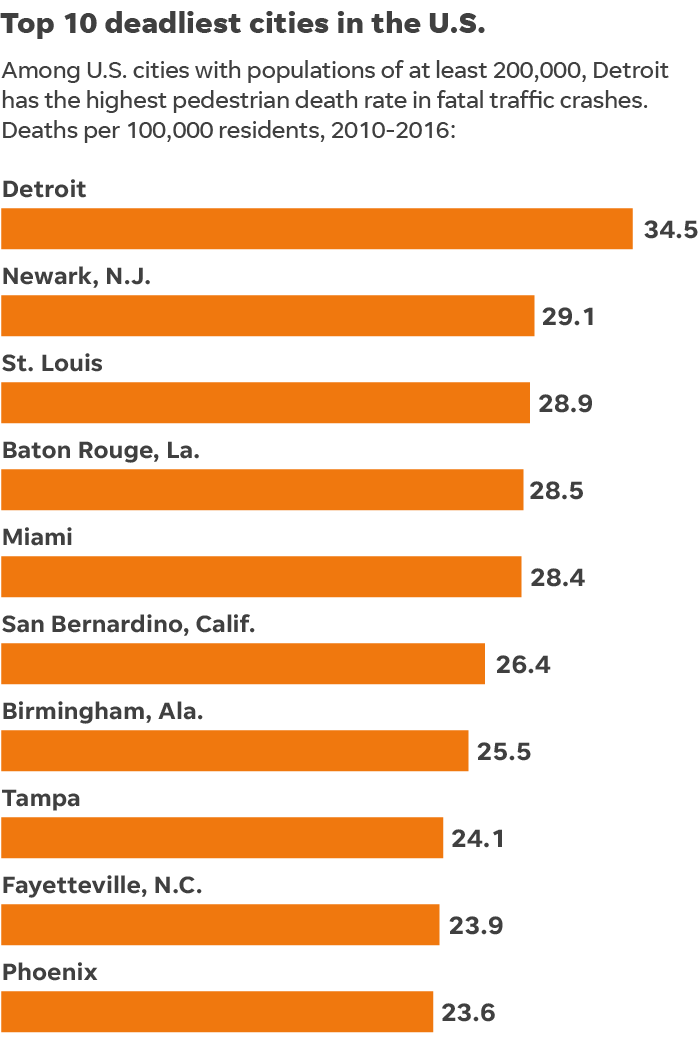

- It is most prominent in cities both in the industrial heartland and warm-weather spots on the nation’s coasts and Sun Belt. Detroit; Newark, New Jersey; St. Louis; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Miami, San Bernardino, California, Birmingham, Alabama; Tampa; Fayetteville, North Carolina; and Phoenix had the 10 highest per-capita death rates among cities with populations of at least 200,000 in 2009-16.

Vehicle safety measures, which the federal government says could save hundreds of pedestrian lives every year, are available but not widely employed by some automakers — nor are they required.

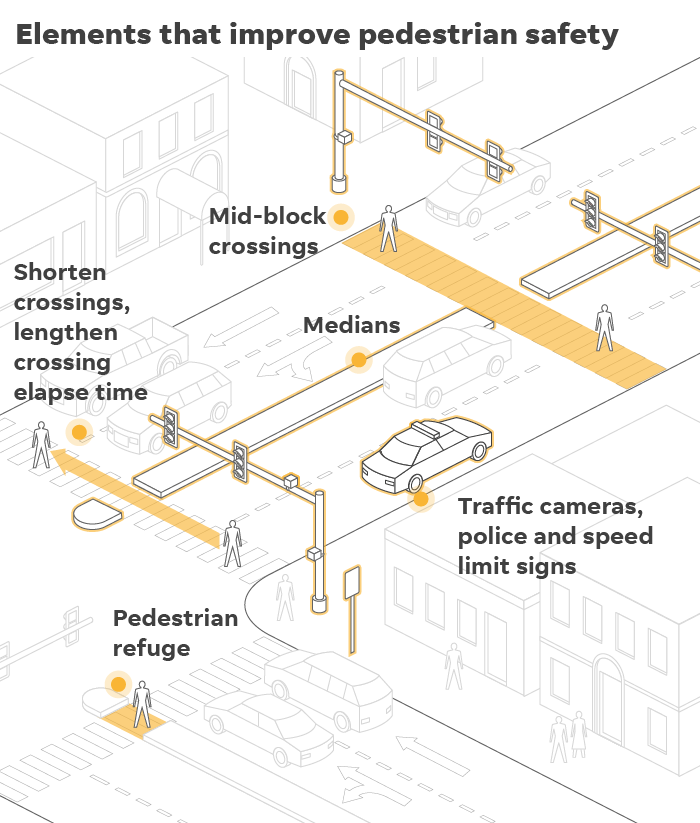

Along with automakers, cities can take action that saves pedestrians. New York City, for example, cut such deaths nearly in half in just four years. The need for steps such as lower speed limits, more midblock crosswalks and better lighting grows in urgency as automakers move strongly toward truck and SUV production.

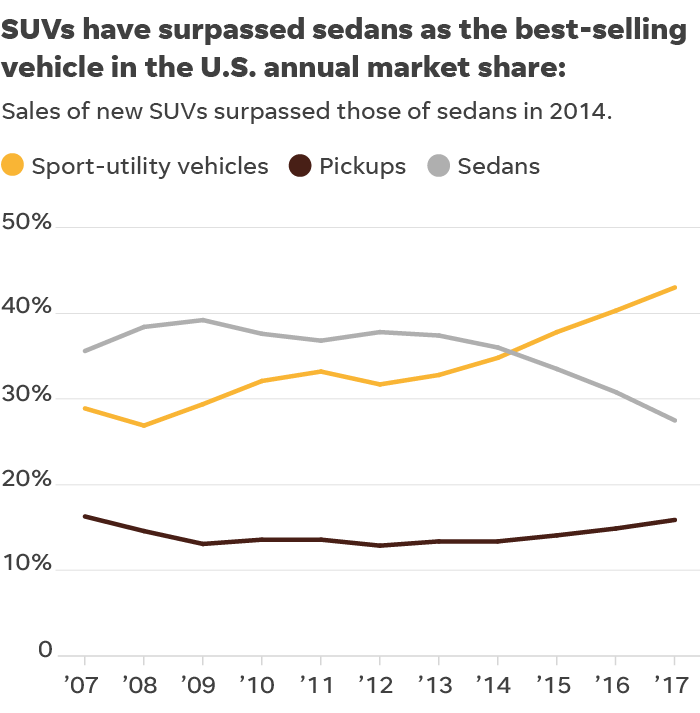

SUV sales topped sedans in 2014; pickups and SUVs now account for 60 percent of new vehicle sales. Ford recently announced plans to discontinue U.S. sales of most passenger cars, while Fiat Chrysler has already done so.

Distraction and other factors

It might seem obvious that a larger vehicle can cause more damage in a crash, whether to a smaller car or an unprotected skull, but some researchers have been hesitant to assign blame for the spike in pedestrian deaths to America’s love of SUVs, in part because various factors are at play in every crash.

Each of the 5,987 pedestrians who died in 2016, according to federal data, had his or her own tragic ending.

Many who died were males, were jaywalking or had alcohol in their systems on multilane roads in urban areas at night. Some might have been distracted, just as vehicle drivers could have been, by texting or talking on cellphones, although data is lacking to quantify distraction.

Some of these other factors also saw increases in recent years, but the SUV component stands out.

Data and safety experts verified that long-standing common factors in pedestrian deaths, such as alcohol and jaywalking at night, did not account for the growth.

A key factor consistently backed by data is growing involvement of higher-profile, blunt-nosed SUVs.

The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety calculated an 81 percent increase in single-vehicle pedestrian fatalities involving SUVs in 2009-16. The Free Press/USA TODAY analysis of the same federal data, counting vehicles that struck and killed pedestrians rather than the number of people killed, showed a 69 percent increase in SUV involvement. The assessment also showed increases each year in the proportion of fatal pedestrian crashes involving the popular vehicles.

Safety standards stalled

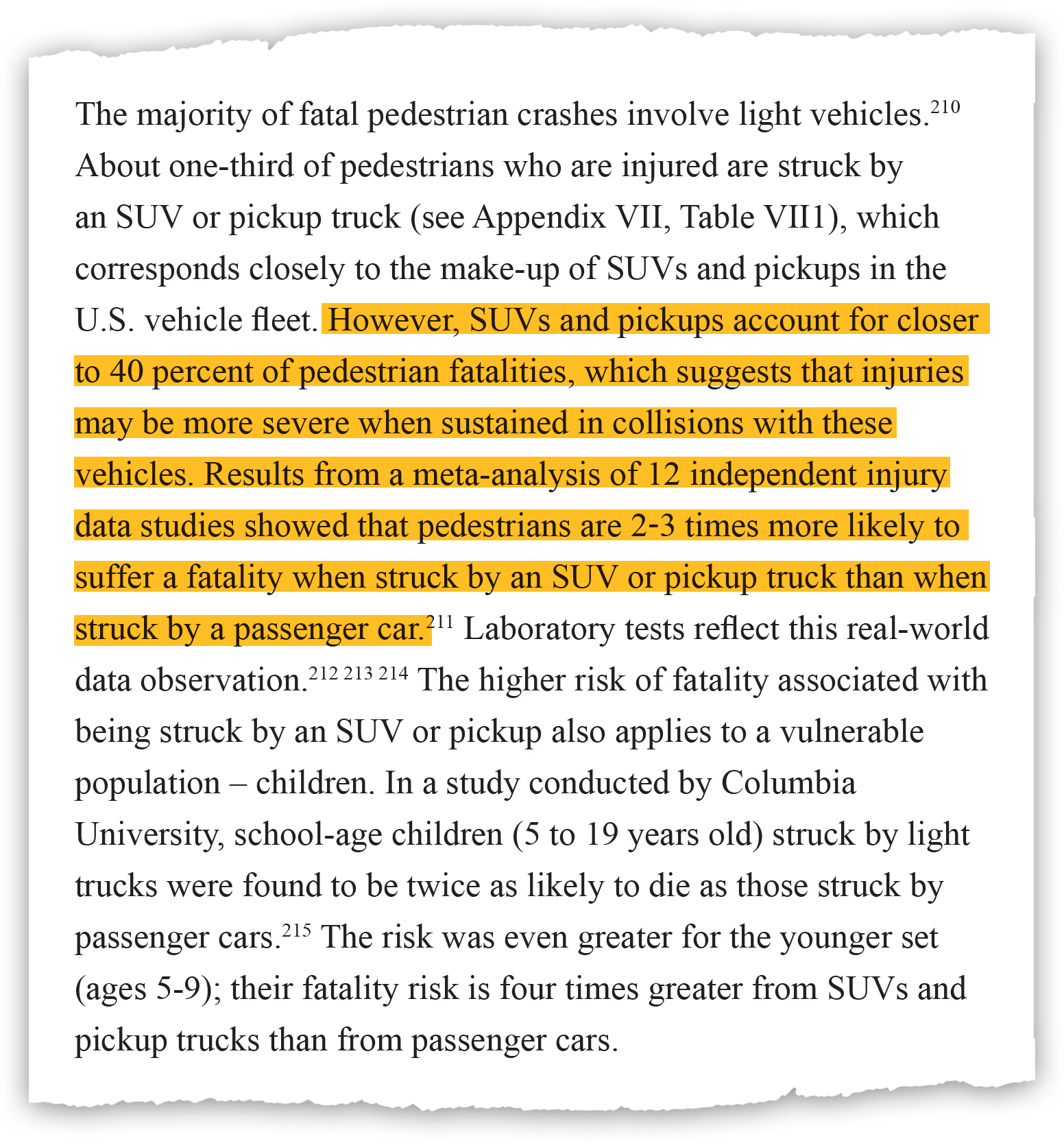

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration made the connection in 2015 that SUVs were deadlier for pedestrians than cars, referenced on page 90 of a 195-page report. That report, citing 12 independent studies of injury data, said pedestrians are two to three times “more likely to suffer a fatality when struck by an SUV or pickup than when struck by a passenger car.”

That report also noted that SUVs and trucks were involved in a third of pedestrian injuries but 40 percent of deaths, indicating that injuries “may be more severe when sustained in collisions with these vehicles.” The proportion of SUVs on the road has only grown in the three years since.

NHTSA, citing the findings in December 2015, announced a plan to overhaul its vehicle-safety rating system to include a new score for pedestrian safety. The plan was to roll out an overhauled New Car Assessment Program, or NCAP, in 2018 for 2019 model-year vehicles.

But that hasn’t happened.

NHTSA did not respond to questions about what caused the delay, although the agency has been without a permanent administrator since President Donald Trump took office. In a statement to the Free Press this week, the agency said it is "working on a proposal for a standard that would require protection against head and leg injuries for pedestrians impacted by the front end of vehicles."

The agency noted that it is studying interactions between motorists, pedestrians and bicyclists, distractions, and strategies that states can use to protect pedestrians and improve education on "this important topic."

NHTSA said earlier that it “plans to continue our efforts to update NCAP by following our process for public engagement, including a public meeting during summer 2018.”

That meeting has not been scheduled and the SUV finding has not been widely shared. The Governors Highway Safety Association earlier this year, for example, reported on its estimates of pedestrian deaths in 2017 and did not cite SUVs as a factor, even speculating that legal marijuana has played a role.

A known factor

As early as 2001, researchers at Rowan University in New Jersey predicted a deadly trend that would reverse a historic drop in pedestrian fatalities, which are now the highest they have been since the George H.W. Bush presidency.

“In the United States, passenger vehicles are shifting from a fleet populated primarily by cars to a fleet dominated by light trucks and vans,” according to their research paper, referencing “light trucks,” which includes SUVs. “Because light trucks are heavier, stiffer and geometrically more blunt than passenger cars, they pose a dramatically different type of threat to pedestrians.”

Hampton Clay Gabler, a professor in the department of biomedical engineering and mechanics at Virginia Tech, wrote that paper with Devon Lefler. Gabler’s interest in the pedestrian issue came from research in other areas showing high death rates for those in cars struck by SUVs.

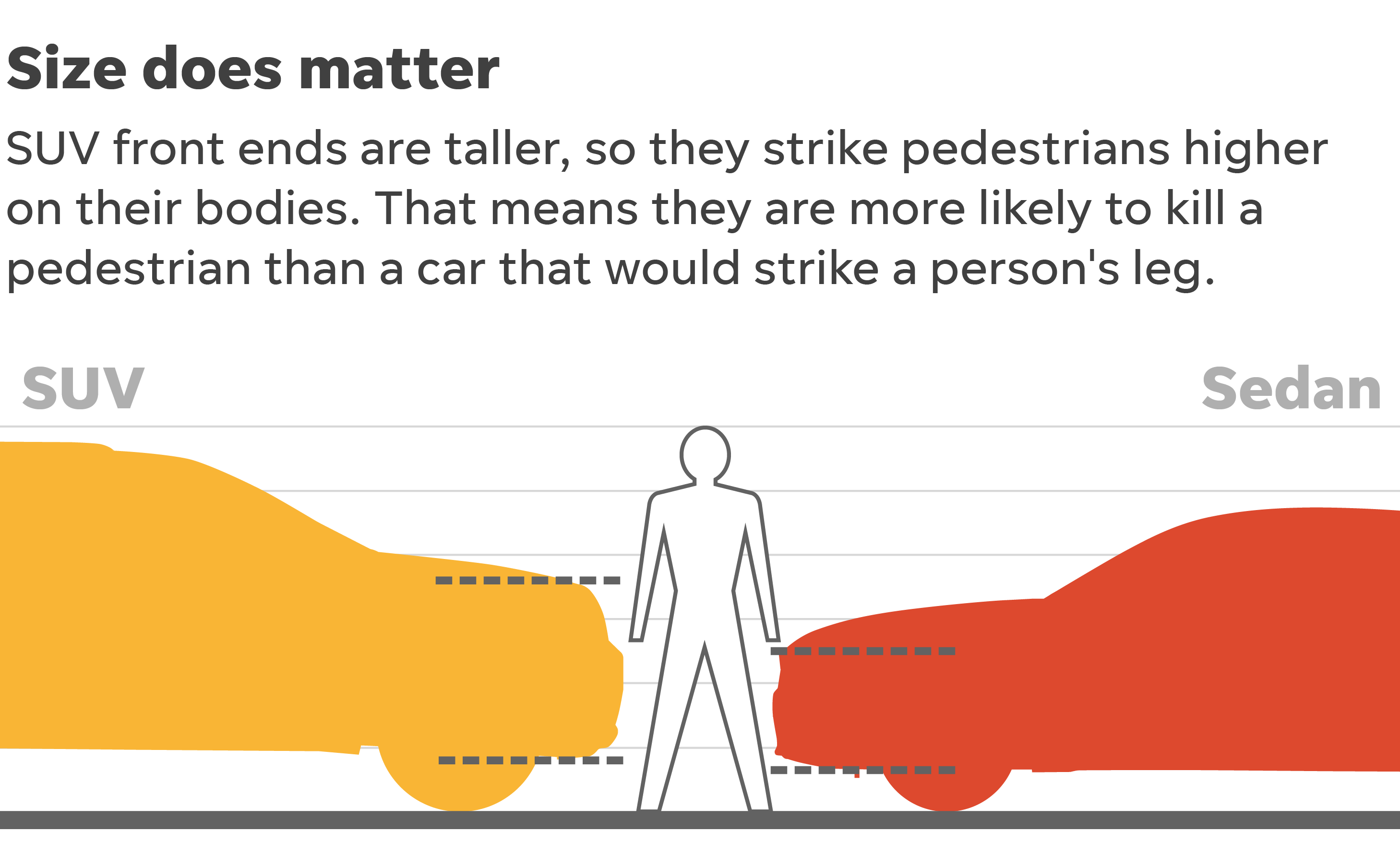

He described the vulnerability of pedestrians when struck by an SUV as a geometry problem of sorts because SUVs and pickups tend to be tall compared with pedestrians and have a blunter front end. That positioning is more likely to put someone’s head or chest in line to be struck during the initial impact with a vehicle.

“(Not to diminish leg injuries but) serious head and chest injuries can actually kill you,” Gabler said in a telephone interview.

More power

Size and profile are not the only vehicle factors involved in the increased fatalities. Power also increased. A report by the Insurance Institute noted that the trend toward more powerful vehicles could contribute to higher speeds, which, in turn, could lead to more crashes and more severe injuries.

“The increasing popularity of SUVs and higher vehicle speeds associated with more powerful vehicles could have contributed to how crashes involving pedestrians have become deadlier,” the study said.

And speed can clearly kill.

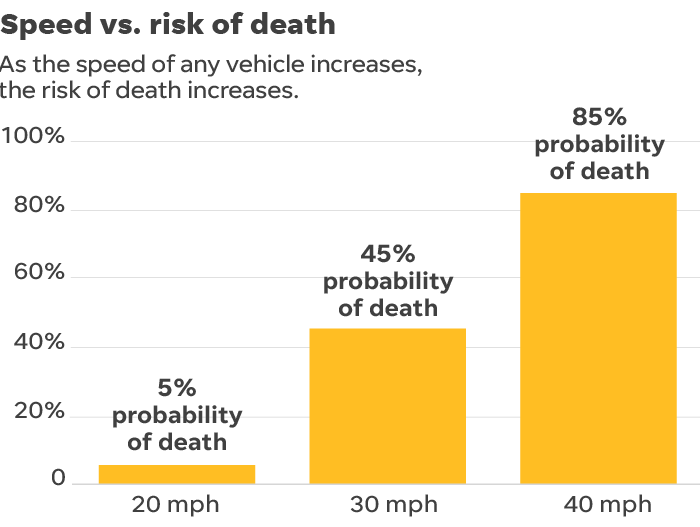

At crashes where a vehicle is traveling 20 mph, 5 percent of pedestrians die. At 30 mph, the percentage increases to 45 percent. At 40 mph, the percentage skyrockets to 85 percent, according to research from 1995 cited by the European Commission, an arm of the European Union.

“Speeding is the most important determinant of whether a pedestrian dies in a crash,” said John Wetmore, a national pedestrian advocate who hosts the public access program “Perils for Pedestrians.”

That belief is supported by Dr. Joe Patton, division head of trauma and acute care surgery at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, a doctor on the front lines of treatment for those injured in crashes.

“Certainly, big cars going fast are worse than little cars going fast, but the speed has a lot to do with it,” Patton said. “I really think the speed makes more of an impact than the size of the vehicle, so you’d rather get hit by a big car going real slow than a small car going real fast because the velocity and the energy of that velocity that it imparts on the person they hit probably plays a bigger role than the size of the car but certainly people are driving bigger cars now.”

Patton called it “intuitive” that bigger vehicles cause worse injuries.

Overall traffic fatalities drop

Pedestrians deaths are not a new phenomenon.

The toll that automobiles have taken on pedestrians dates to the beginnings of the automotive age. In 1896, Britain saw its first pedestrian death by a motor vehicle when a woman was struck in south London. That same year, the country raised its speed limit from 4 to 14 mph, according to Steve Parissien’s “The Life of the Automobile.”

The first U.S. pedestrian death by automobile came in 1899 when a man was struck and killed in New York after hopping off a trolley, Parissien noted.

The more than 8,000 pedestrians killed in the United States in 1979 represent a high point, according to the Insurance Institute, but more than 51,000 people died in motor vehicle crashes that year. Motor vehicle crash deaths had fallen to 37,461 in 2016, according to NHTSA data, as vehicle safety improved.

Pedestrians are not seeing the benefits of the lifesaving safety improvements that have helped reduce total traffic fatalities. Pedestrians represent 16 percent of those killed in traffic crashes in 2016, a steady increase over the past decade.

Those who die, however, are not simply statistics.

In Memphis, 70-year-old Lee Soult was one of eight pedestrians killed so far this year. Soult was struck by a pickup and killed as he crossed a city street outside a crosswalk on an April evening. His brother, Bob Soult, mourned the fact that Lee, who retired from a glove company in 2013, would not “get to enjoy his retirement and his life a little while longer.” The truck driver was not charged in the crash.

In Detroit, the 2016 death of 64-year-old Maurice Parker Mims prompted a campaign to track down the hit-and-run driver of a Chevrolet Impala, which struck Mims in a crosswalk on Veterans Day, authorities said. Mims, a Marine veteran and street artist in Detroit’s Greektown neighborhood, had been picked as metro Detroit’s “Most Outstanding Volunteer” by the American Red Cross.

Gilberto Ramon Ortiz, 23, was accused of taking the car to a repair shop to have the windshield replaced after the crash, according to the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office. A jury trial on charges of tampering with evidence and obstruction of justice is scheduled for July.

Back in Phoenix, Karen Bonta died at the scene of the March crash. Her husband, Robert, died 61 minutes later at an area hospital.

Ronald Doornbos, whose wife was killed, died this month in Calgary, where his family said he had been "minimally conscious."

The crash on a multilane road with a 35-mph speed limit came during a deadly stretch this spring for pedestrians in the nation's fifth-largest metro area, with 10 people dying in nine days.

Authorities have said Bradshaw, the driver, didn't appear to be impaired. They have not disclosed how fast they think he was driving, but whether he was distracted remains part of the investigation.

Tim Budnick, a business owner near where the crash happened, said he heard tires squealing and noise he thought was the SUV ramming into a concrete curb. When he walked outside, he learned the sound was actually the vehicle hitting people.

“When I saw them, I was expecting some of them to start getting up, saying things like ‘Oh, my wrist,’ or ‘My shoulder hurts,’ ” Budnick said. “I heard nothing. All four of them were lying there.”

Known safety measures

As the number of pedestrian fatalities has spiked, some communities have worked to change the narrative.

Pedestrian safety advocates have pointed to efforts like those in New York as examples for other cities. Through a combination of enforcement targeted at driver behavior, lowered speed limits and training for cab drivers, the city saw its pedestrian deaths last year drop to their lowest number, 101, since the city began tracking the statistic in 1910.

In Seattle, Rainier Avenue in 2015 was reduced from four lanes to three, enforcement was stepped up and other changes made it easier for pedestrians to cross. Eleven people died between 2004 and 2014 on one portion of the road, but no one has died in that section since the changes were made, according to a Seattle Department of Transportation report.

Infrastructure changes designed to better protect pedestrians by reducing traffic lanes, adding pedestrian refuge islands and midblock crossings are often credited with reducing speeds and improving safety. That’s part of the vision for a major thoroughfare on Detroit’s east side. East Jefferson Avenue, a multilane street that connects the city to the suburban Grosse Pointe communities, is undergoing a "road diet," dropping from seven lanes to five, adding protected bike lanes and improving crosswalks.

In Detroit, which has the highest per-capita pedestrian death rate among large cities, deaths dropped in 2016, after the city, as part of its emergence from bankruptcy, added more than 60,000 new streetlights.

Nationally, speed and red-light cameras are also credited with making streets safer for pedestrians. As of May, 421 communities were using red-light cameras and 143 communities were using speed cameras to enforce traffic laws, according to the Insurance Institute.

Cities, including Honolulu and Montclair, California, have focused on pedestrians to reduce fatalities. Both cities passed laws against texting and walking when crossing streets. Honolulu council member Brandon Elefante told the Free Press in May that “the hope is more municipalities will adopt similar language looking at pedestrians and vehicles.”

Automatic braking

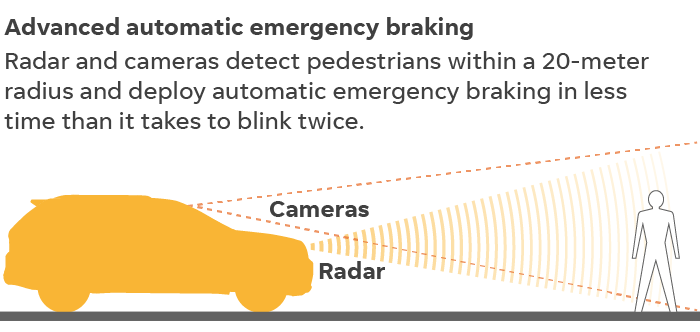

Vehicle safety features, however, are believed to be just as crucial to reducing pedestrian deaths.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Volpe Center have found that the use of pedestrian crash avoidance/mitigation systems and features such as automatic emergency braking, could reduce up to 5,000 vehicle-to-pedestrian crashes and 810 fatal crashes per year.

Most automakers have voluntarily committed to installing low-speed automatic emergency braking systems by 2022, but the progress to date varies greatly, according to NHTSA.

Some brands make automatic emergency braking standard — Tesla (99 percent), Mercedes-Benz (96 percent), Volvo (68 percent) and Toyota (56 percent).

Others, as of last year, produced only a small portion of their fleet with the technology — Fiat Chrysler (6 percent), Mitsubishi (3 percent), Ford (2 percent) and Jaguar/Land Rover and Porsche (none). General Motors produced 20 percent of its fleet with AEB.

Fiat Chrysler spokesman Eric Mayne, said the automaker will meet the standard by 2022. He noted that automatic emergency braking is currently available on 15 models in nine segments.

Elizabeth Weigandt, a Ford spokesperson, said Ford began offering its pre-collision assist with AEB on the 2017 Fusion and now makes it available on seven other models.

"We will standardize AEB on 15 percent of vehicles in 2018 and are well ahead of meeting the agreement to standardize across our lineup by 2022," she said.

General Motors spokesman Tom Wilkinson noted that "GM was part of the agreement to make AEB standard in the U.S. by the end of 2022 and we will meet that target. More than two-thirds of our models now have AEB available."

Catherine Chase, president of Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, said the voluntary nature of the 2022 commitment means automakers can walk away if they choose and pedestrian-specific crash avoidance technology might not be included.

“We think that they should be put in as standard equipment in all vehicles,” she said.

The group’s research director, Shaun Kildare, noted that it’s not simply a delay of a year or two. Because it takes about 10 years for the fleet to change, delays in implementing new technology can mean decades before the improvements are in most vehicles on the road.

From a practical standpoint, automakers should be pushing forward because of the rush to develop autonomous vehicles, Kildare said.

“This is a fundamental technology to reaching autonomous vehicles. You need to know how your system is going to identify objects on the road and if you’re going to be able to respond to it,” Kildare said, noting the risks highlighted by this year’s fatal self-driving Uber crash in Arizona. “Why isn’t every automaker putting these in so we know we’re not killing people needlessly?”

But Chase said automakers tend to resist mandates, preferring to decide on their own what should and should not go into a vehicle. Some of that resistance involves concerns about cost.

Once a technology is in wide use, however, the cost tends to decrease, Chase said. That technology can also become a selling point, she said, using the example of backup cameras. Chase said there had been resistance to adding backup cameras, which became required on new vehicles in the U.S. in May, but drivers who are familiar with them now demand them.

The Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, which represents the industry on policy issues, views advanced driver-assistance and crash avoidance technology “as a much better approach” to improving pedestrian safety than an overhauled New Car Assessment Program that had been proposed by NHTSA, spokeswoman Gloria Bergquist said in an email.

“These technologies are well researched and have proved to be beneficial,” Bergquist said.

The alliance’s members appear to be split on whether the pedestrian protection rating is a good move.

For example, General Motors told NHTSA regulators in a February 2016 letter that it did not support a separate rating for pedestrian safety, saying “an overall crash performance category is the appropriate place to address the crashworthiness elements of pedestrian protection.”

But Toyota enthusiastically supported the agency’s recommendation. It “will allow consumers to more easily understand a vehicle’s safety performance,” the Japanese automaker told NHTSA in its own February 2016 letter.

European standards

Automakers face a different landscape in Europe, where pedestrian safety is a key rating component. The rating agency Euro NCAP includes detailed information on its website about various vehicles. Color-coded images even show where pedestrian impact protection is good, such as on the hood (or bonnet) of a 2017 BMW 6 Series GT, or where it is poor on the same vehicle, such as along a strip above the grille.

“Euro NCAP has encouraged vehicle manufacturers to consider pedestrian impacts in the vehicle design and this can be seen most commonly as space available beneath the hood of the vehicle, padding to bumper areas, and more (compliant) structures at the base of the windscreen and on the bonnet leading edge. The space between the hood and engine allows the bonnet to absorb the impact of the pedestrian’s head before it contacts the very hard engine structures beneath. A similar principle is also applied to the bumper/front end to protect the vulnerable knee joint of a pedestrian,” according to the agency

The agency said that the testing had led to innovative countermeasures such as the deployable hood, which can lift up slightly, and external airbags, both designed to cushion the blow.

Euro NCAP, which recently added testing of emergency braking systems to cover cyclists, noted that about 25,000 people die in traffic crashes in Europe each year and almost half of those killed in 2017 were vulnerable road users.

“Moreover, for every person killed in traffic crashes, about five more suffer serious injuries with life-changing consequences. Serious injuries are common and often costlier to the society because of longtime rehabilitation and health-care needs. The majority of the seriously injured on Europe's roads are vulnerable road users, i.e. pedestrians, cyclists and drivers of powered two-wheelers,” the agency said.

“The technology is really going to be our savior,” said Tom Mayor, industrial manufacturing strategy practice leader at the consulting firm KPMG, who has had discussions with auto companies about improving in-vehicle infotainment systems. “In the short term, we’ve been getting dumber faster than our cars have been making us smarter.”

Friday, June 29, 2018

White America’s Age-Old, Misguided Obsession With Civility - Note for a discussion, "E Pluribus Unum? What Keeps the United States United."

By Thomas J. Sugrue, New York Times, June 29, 2018

Mr. Sugrue is a professor of history and social and cultural analysis and author.

Image from article, with caption: 1n 1963 the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led a mass demonstration in Birmingham, Ala., to pressure the Kennedy administration to actively defend the civil rights of black citizens.

Recent disruptive protests — from diners at Mexican restaurants in the capital calling the White House adviser Stephen Miller a fascist to protesters in Pittsburgh blocking rush-hour traffic after a police shooting of an unarmed teen — have provoked bipartisan alarm. CNN commentator David Gergen, adviser to every president from Nixon through Clinton, compared the anti-Trump resistance unfavorably to 1960s protests, saying, “The antiwar movement in Vietnam, the civil rights movement in the ’60s and early ’70s, both of those were more civil in tone — even the antiwar movement was more civil in tone, but certainly the civil rights movement, among the people who were protesting.”

But those who say that the civil rights movement prevailed because of civil dialogue misunderstand protest and political change.

Image from article, with caption: As a candidate in 2016, Donald Trump used his own lack of civility to win the election.

This misunderstanding is widespread. Democratic leaders have lashed out at an epidemic of uncivil behavior in their own ranks. In a tweet, the House minority leader, Nancy Pelosi, denounced both “Trump’s daily lack of civility” and angry liberal responses “that are predictable but unacceptable.” Senator Charles Schumer described the “harassment of political opponents” as “not American.” His alternative: polite debate. “If you disagree with someone or something, stand up, make your voice heard, explain why you think they’re wrong, and why you’re right.” Democrat Cory A. Booker joined the chorus. “We’ve got to get to a point in our country where we can talk to each other, where we are all seeking a more beloved community. And some of those tactics that people are advocating for, to me, don’t reflect that spirit.”

The theme: We need a little more love, a little more King, a dollop of Gandhi. Be polite, be civil, present arguments thoughtfully and reasonably. Appeal to people’s better angels. Take the moral high ground above Trump and his supporters’ low road. Above all, don’t disrupt.

This sugarcoating of protest has a long history. During the last major skirmish in the civility wars two decades ago, when President Bill Clinton held a national conversation about race to dampen tempers about welfare reform, affirmative action, and a controversial crime bill, the Yale law professor Stephen Carter argued that civil rights protesters were “loving” and “civil in their dissent against a system willing and ready to destroy them.” King, argued Carter, “understood that uncivil dialogue serves no democratic function.”

But in fact, civil rights leaders, while they did believe in the power of nonviolence, knew that their success depended on disruption and coercion as much — sometimes more — than on dialogue and persuasion. They knew that the vast majority of whites who were indifferent or openly hostile to the demands of civil rights would not be moved by appeals to the American creed or to bromides about liberty and justice for all. Polite words would not change their behavior.

For King and his allies, the key moment was spring 1963, a contentious season when polite discourse gave way to what many called the “Negro Revolt.” That year, the threat of disruption loomed large. King led a mass demonstration in Birmingham, Ala., deliberately planned to provoke police violence. After the infamous police commissioner Bull Connor sicced police dogs on schoolchildren and arrested hundreds, including King, angry black protesters looted Birmingham’s downtown shopping district. Protesters against workplace discrimination in Philadelphia and New York deployed increasingly disruptive tactics, including blockading construction sites, chaining themselves to cranes, and clashing with law enforcement officials. Police forces around the United States began girding for what they feared was an impending race war.

Whites both North and South, moderate and conservative, continued to denounce advocates of civil rights as “un-American” and destructive throughout the 1960s. Agonized moderates argued that mass protest was counterproductive. It would alienate potential white allies and set the goal of racial equality back years, if not decades. Conservatives more harshly criticized the movement. National Review charged “King and his associates” with “deliberately undermining the foundations of internal order in this country. With their rabble-rousing demagogy, they have been cracking the ‘cake of custom’ that holds us together.” By 1966, more than two-thirds of Americans disapproved of King.

King aimed some of his harshest words toward advocates of civility, whose concerns aligned with the hand-wringing of many of today’s politicians and pundits. From his Birmingham jail cell, King wrote: “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action’.” King knew that whites’ insistence on civility usually stymied civil rights.

Those methods of direct action — disruptive and threatening — spurred the Kennedy administration to move decisively. On June 11, the president addressed the nation on the “fires of frustration and discord that are burning in every city, North and South, where legal remedies are not at hand.” Kennedy, like today’s advocates of civility, was skeptical of “passionate movements.” He criticized “demonstrations, parades and protests which create tensions and threaten violence and threaten lives,’ and argued, “it is better to settle these matters in the courts than on the streets.” But he also had to put out those fires. He tasked his staff with drafting what could eventually become the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. Dialogue was necessary but far from sufficient for passage of civil rights laws. Disruption catalyzed change.

That history is a reminder that civility is in the eye of the beholder. And when the beholder wants to maintain an unequal status quo, it’s easy to accuse picketers, protesters, and preachers alike of incivility, as much because of their message as their methods. For those upset by disruptive protests, the history of civil rights offers an unsettling reminder that the path to change is seldom polite.

Correction: June 29, 2018

A previous version of this piece misstated Bull Connor’s title. He was a police commissioner, not the police chief.

Thomas J. Sugrue is professor of history and social and cultural analysis at New York University and author of Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North.

Does American ‘Tribalism’ End in a Compromise, or a Fight? - Note for a discussion, "E Pluribus Unum? What Keeps the United States United."

"First Words" column by Laila Lalami, New York Times

image from article

Early in June, the valedictorian at Bell County High School in southeastern Kentucky delivered a graduation speech filled with inspirational quotations that, he said with a twinkle in his eye, he’d found on Google. One line, in particular, drew wild applause from the crowd in this conservative part of the country: “ ‘Don’t just get involved. Fight for your seat at the table. Better yet, fight for a seat at the head of the table.’ — Donald J. Trump.” As people cheered, though, the valedictorian issued a correction: “Just kidding, that was Barack Obama.” Right away, the applause died down, and a boo could be heard. The identity of the messenger, it was painfully evident, mattered more than the content of the message.

When Americans hear about “tribalism,” they often imagine a faraway land where one ethnic or religious faction mercilessly persecutes another for generations. Only recently have many in this country begun to appraise the extent of the tribalism at home. Writing for The Times’s Op-Ed page in February, Amy Chua, the Yale law professor who once extolled the merits of “tiger moms,” warned about the dangers of a “zero-sum tribalist contest.” Jonah Goldberg, the conservative columnist and pundit who once railed against “liberal fascism,” recently went on NPR’s “Morning Edition” to sound the alarm on “a cheap form of tribalism,” telling the host Steve Inskeep that “people are retreating into their little cocoons.” And in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, Senator Orrin Hatch lamented that identity politics — “tribalism by another name” — could turn the nation into “a divided country of ideological ghettos.”

In its first sense, tribalism refers to the organization of people along lines of common ancestry or joint identity for the purpose of exercising political power — as the indigenous people of many parts of the world, including the Americas, have long done. But over time, as new forms of governance appeared — city-states, kingdoms and especially empires, which controlled vast colonies with different races, cultures and languages — tribalism came to be seen as crude and antiquated, a political structure that could never hope to address the challenges of large states. And now, in the modern era, the word is used almost exclusively in its second, derogatory sense, to suggest an irrational loyalty to your people.

The impulse to belong to a clan is deeply human, however, and new tribes continue to form, organized not around ancestry but along fuzzier lines of ideology or demography. Modern tribes, like ancient ones, have idiosyncratic languages; one faction might speak of “illegal aliens,” “traditional families” and “the life of the unborn,” while the other talks of “undocumented workers,” “marriage equality” and “my body, my choice.” They rule over separate territories, listen to different oracles, uphold distinct values and dismiss contradictory information as unreliable propaganda or “fake news.”

Above all, tribe members protect one another from perceived attacks by outsiders. Last April, when the MSNBC host Joy Reid was found to have posted homophobic content on a now-defunct blog (and claimed, dubiously, to have been hacked), many liberals rallied to her side anyway, pointing out that the posts were more than 10 years old and urging others to accept her profuse apologies. Had such posts been attributed to a Fox News personality, however, it’s almost certain those same liberals would have offered no opportunity for forgiveness. The gift of absolution is given within a tribe, and rarely outside it.

Political tribes can organize along stark lines: the working class versus the 1 percent, baby boomers versus millennials, city dwellers versus rural people. But they can also be more nebulous, forming around subtleties of education, lifestyle or cultural taste. Some years ago, when Howard Dean was the front-runner for the Democratic nomination for the presidency, the conservative PAC Club for Growth ran a TV ad in Iowa featuring an elderly white couple being asked about Dean’s tax proposal. “What do I think?” the husband says. “I think Howard Dean should take his tax-hiking, government-expanding, latte-drinking, sushi-eating, Volvo-driving, New York Times-reading —” Then his wife interrupts: “body-piercing, Hollywood-loving, left-wing freak show back to Vermont, where it belongs.”

The question was at least putatively about Dean’s plan to repeal George W. Bush’s tax cuts, but instead of eliciting a coherent opinion on how much tax should reasonably be withheld, from whom and for what services, it provoked a rant against a particular group of people, who were characterized almost entirely through their lifestyle and consumer choices. There was no need to talk policy, because the policy was reframed as an embrace of one tribe and a rejection of the other.

In principle, the United States is a country where various tribes are supposed to work in coalition to form what the founders called “a more perfect union.” Americans also pride themselves on having a “melting pot” model of immigration, in which each new group is thrown into the mix, contributing to the overall sustenance of the nation. But the reality is that, for most of this country’s history, one tribe has held power, deciding who was allowed to settle the land and who could be dispossessed, who was free and who was enslaved, who had the right to vote and who did not. The hegemony of white landowners prompted few, if any, complaints about tribalism in the national conversation. It was only when other factions began to demand justice and recognition — the “seat at the table” that Trump, but not Obama, was applauded for encouraging people to seek — that the debate about which tribe holds power became explicit rather than implicit.

It is not a coincidence, then, that use of the word “tribalism” in print increased significantly during the civil rights struggles, anti-war protests and cultural clashes of the 1960s, reaching a peak in 1972, when Richard Nixon campaigned for and won a second term. That era was characterized by turmoil, both abroad and here in the United States, where tribes rebelled against one another in nearly every public arena, from draft offices to college campuses to lunch counters. After Nixon’s resignation and the end of the Vietnam War, complaints about tribalism declined steadily, only to rise again in the 1990s.

Why the 1990s? Over the course of his presidency, Bill Clinton moved the Democratic Party to the right: He deregulated banks, cut welfare programs, signed the Defense of Marriage Act into law, built a border wall between San Diego and Tijuana and expanded mass incarceration. These are not progressive ideas, which left Republicans with few concrete policies that could distinguish them from Democrats. Republicans did, however, have culture — and, eventually, character. When Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky surfaced in 1998, conservatives attacked him as the symbol of a lost and immoral society, while liberals minimized his offenses and portrayed the young intern as a harlot. Twenty years later, the two tribes would switch sides, with liberals denouncing Donald Trump for sexual predation while conservatives, including white evangelicals, rallied around him.

Political tribes often display similar group behavior, but this doesn’t mean that the values they hold are equivalent. Tearing migrant children away from their parents, for instance, is not a morally neutral policy. In moments like these, complaints about tribalism can be politically expedient — a way of making even the most consequential debate seem like a mere spat between loyalists on either side. (Where was this passion for the fates of asylum seekers, some conservatives have asked, during the Obama administration?) By reducing every question to tribalist point-scoring, it becomes easier to escape the moral implications of taking an asylum-seeking child from his or her mother and incarcerating them hundreds of miles apart.

Some people think that dialogue and debate can help the United States defeat its current tribalism. If only we could calmly talk about our differences, the argument goes, we would reach some compromise. But not all disagreements are bridgeable. The Union and the Confederacy did not resolve their differences through dialogue; it was a civil war that put an end to slavery. Jim Crow laws were defeated through mass protests and civil disobedience. Schools were desegregated though a Supreme Court decision, which had to be implemented with the help of the National Guard. The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed as a political necessity during World War II. Some fights are not talked away; they are, in the end, either won or lost.

This is not to say that tribal impasses of the moment can’t be broken. But it is generally not a good idea to expect people on the receiving end of brutal policies — like families broken apart by police violence, immigration raids, travel bans or anti-L.G.B.T. discrimination — to hash out a compromise over sweet tea. “Maybe we pushed too far,” Barack Obama is quoted as saying in a new memoir by Benjamin Rhodes, one of his closest aides. “Maybe people just want to fall back into their tribe.” What the ever-compromising Obama doesn’t consider is that resolution sometimes requires pushing even further.

Laila Lalami is the author, most recently, of “The Moor’s Account.” She last wrote a First Words column about what it takes to “assimilate” in America.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)