Courtland Milloy, The Washington Post, November 27; original article contains links

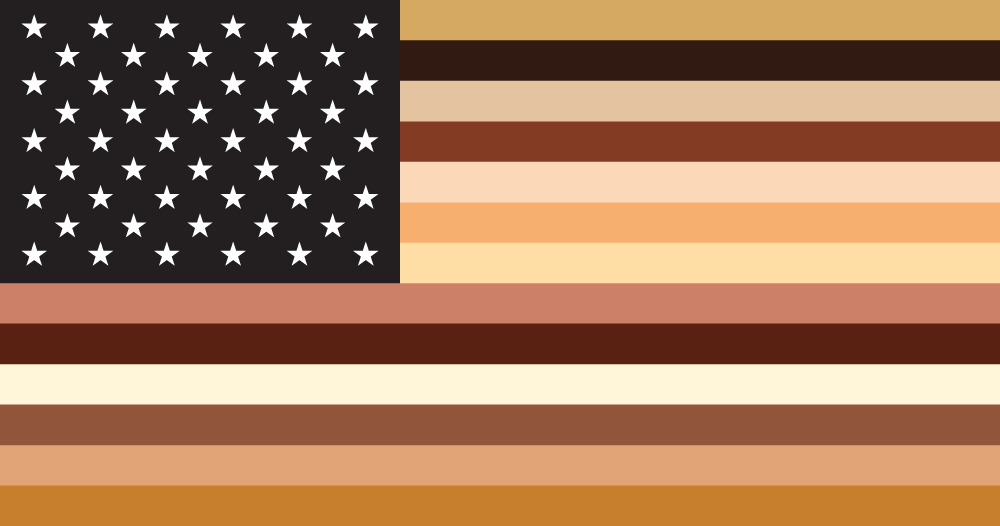

image from

Kwame Anthony Appiah, a professor of philosophy and law at New York University, has been hammering that fact for more than 40 years. It is, Appiah says, “racial antirealism.”

Sounds like mental illness.

Appiah grew up in Ghana and earned a doctorate from Cambridge. A cultural theorist, referred to by some as a “postmodern Socrates,” he was presented with a National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama in 2012.

Appiah was back in Washington recently to discuss his new book, “The Lies That Bind.” The title pretty much sums up our national predicament on race — a society organized into conflicting groups. [JB emphasis] One of the most critical of those lies is fueled by a delusion based primarily on skin color.

While much of “the scientific superstructure of race has been dismantled in the past century,” Appiah writes in the book, “the world outside the sciences hasn’t taken much notice. Too many of us remain captive to a perilous cartography of color.”

We’ve seen a resurgence of that racial peril in recent years, most recently in political campaigns marred with racial invective — in Mississippi, Georgia, Florida and even in the progressive District of Columbia.

In the race for U.S. Senate in Mississippi, a black man and a white woman are competing. In a state with one of the highest numbers of recorded lynchings, the white candidate has joked about a “public hanging.”

In Georgia, a robo-call labeled the black female candidate for governor “a poor man’s Aunt Jemima,” a reference to an image that has racist connotations. In Florida, a white candidate for governor told voters not to vote for the black candidate because they couldn’t afford to “monkey this up.”

And in the liberal District, a white Jewish candidate for an at-large council seat was portrayed as an outsider in corners of the city where many blacks feel they’re being left behind or pushed out.

In an interview, I asked Appiah for his take on the emotional havoc that race is wreaking on us — specifically on white and black people, the two groups at the center of the friction.

Both groups are paying a steep price for being bound by the lie.

“There are a lot of anxieties around race,” Appiah said.

Fear and anger among white people who believe black people are less than and unequal. Fear and anger among black people for whom historic atrocities by white people make it impossible to trust fully.

“I feel we are going through a low period,” he said. “President Trump didn’t start it,” Appiah said, referring to Trump’s appeal to and embrace of people and policies that have been at minimum inflammatory. But, Appiah said, Trump made it worse. Like his distorted use of the word “nationalism,” which might have been the root of a shared American identity. Instead, Trump turned it into an appeal to racism.

“What he is doing is dog whistling to people who call themselves nationalist but who are really a racially identified people who want America to be a white nation. Responsible people don’t do that, because in a society so divided, you get violence, and at the end of that road is ethnic cleansing and genocide. And once you set these things in motion, you can’t control them.”

The shooting up of black churches and synagogues provides ample proof.

“The fact that these people are clearly unbalanced doesn’t mean that they are not being affected by the trends in the culture,” Appiah said. “When you encourage groups that are anti-Semitic and racist, you encourage crazy people to do bad things. Even people who are not clinically insane will sit in front of a [computer screen] sharing hateful language that can only lead to violence in the end.”

White people aren’t the only ones to have bought into the fallacy of race.

Far too many black people have internalized the legacies of the old racist structure, Appiah said. It affects how you respond to challenges, how you think about yourself, he said. “There is also a constant barrage of negativity about black people in the culture, and it’s bound to affect you.”

Two weeks ago, I wrote a column questioning why more black men had not spoken up against the way Trump had mistreated black female elected officials and journalists. I asked Appiah what he thought about such an appeal to racial solidarity.

He noted that historically, oppressed groups often band together to fight injustice. However, any notion that 40 million “black” people felt the same way because of their race was unrealistic.

And unproductive.

“There is a danger in making racial identities too central to our conceptions of ours,” he says.

But there’s also no getting around it.

With racial identity comes a set of norms to which members are expected to adhere, but these norms can be in conflict with personal ambition and freedom of expression.

“I think it’s important to know how incredibly diverse black people are,” he said. “If I say, ‘Imagine the face of a black man,’ people will have a picture, but only a tiny proportion will fit that picture.”

Appiah’s father, Joseph Emmanuel Appiah, was a lawyer, politician and Ghanaian anti-colonial activist. He was black. His mother, Peggy Appiah, was an English aristocrat. She was white.

Asked about his own racial identification, he said, “People know I’m not white.”

That’s how the construct of race plays out.

You can’t wish the race problem away, Appiah says.

“A ‘white’ person might not want to build an identity around race, but even if you reject [seeing yourself] as white, your race still affects how you live because other people respond to it, whether you like it or not.”

For black people, the identity formed around race has an even greater impact — on education, jobs, housing, simply living. That’s why those in power, those who have benefited from the construct of racial hierarchy, need to speak out.

“When you see a situation that produces injustice, you can do something about it,” Appiah said.

Race, gender, political party — none of that should matter. Hundreds of years of laws implemented with the goal of keeping a group of people down on the basis of their skin color prove that it does matter.

The fiction of race has become truth.

No comments:

Post a Comment